Lovely cartoon in the current New Yorker. Shows the reception desk of the Flat Earth Society. Behind the receptionist are clocks labelled New York, London, Paris, Beijing and Tokyo — all showing the time as 10:10!

Category Archives: Asides

Innocents abroad

“An Ambassador”, says the old joke, “is an honest man sent abroad to lie for his country”. The only US Ambassador I’ve met was a Californian automobile salesman. (Well, he owned a whole string of dealerships, and I guessed owed his position not to mastery of statecraft but to the size of his campaign contributions.) It was during the Iraq war and he gave a public lecture which never once mentioned the war. And then I forgot all about him, until I came on this piece in Politico by James Bruno arguing that one reason the Kremlin is running rings round the US in Europe is the relative incompetence of American ambassadors compared to their Russian counterparts.

Bruno examines the diplomatic representation of the two countries in three critical European capitals: Berlin, Oslo and Budapest.

Berlin

The Russian ambassador to Germany, Vladimir Grinin, who joined the diplomatic service in 1971, has served in Germany in multiple tours totaling 17 years, in addition to four years in Austria as ambassador. He is fluent in German and English. He has held a variety of posts in the Russian Foreign Ministry concentrating on European affairs. Berlin is his fourth ambassadorship.

The U.S. ambassador to Germany, John B. Emerson, has seven months of diplomatic service (since his arrival in Berlin) and speaks no German. A business and entertainment lawyer, Emerson has campaigned for Democrats ranging from Gary Hart to Bill Clinton. He bundled $2,961,800 for Barack Obama’s campaigns.

Oslo

Vyacheslav Pavlovskiy has been Moscow’s envoy in Oslo since 2010. A MGIMO graduate and 36-year diplomatic veteran, he speaks three foreign languages.

President Obama’s nominee as ambassador to Norway, hotel magnate George Tsunis, bundled $988,550 for Obama’s 2012 campaign. He so botched his Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing in February with displays of ignorance about the country to which he is to be posted that Norway’s media went ballistic and he became a laughingstock domestically. He is yet to be confirmed.

Budapest

Russian envoy Alexander Tolkach, a 39-year Foreign Ministry veteran and MGIMO alumnus, is on his second ambassadorship; he speaks three foreign languages.

Colleen Bell, a producer of a popular TV soap opera with no professional foreign affairs background, snagged the nomination of U.S. ambassador to Hungary with $2,191,835 in bundled donations to President Obama. She stumbled nearly as badly as Tsunis before her Senate hearing with her incoherent, rambling responses to basic questions on U.S.-Hungarian relations. She also awaits Senate confirmation.

The wit and wisdom of Vladimir Putin

“There are three ways to influence people: blackmail, vodka, and the threat to kill.”

President Putin quoted in an article by the Russian muckraking journalist Artyom Borovik who died in 2000 in a still-unsolved Moscow plane accident days after producing a scathing article about an ascendant Russian politician, one Vladimir Putin, who was about to become president.

Department of Unintended Consequences

Well, what do you know? This from the New York Times

The end of the war in Iraq and the winding down of the war in Afghanistan mean that the graduates of the West Point class of 2014 will have a more difficult time advancing in a military in which combat experience, particularly since the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, has been crucial to promotion. They are also very likely to find themselves in the awkward position of leading men and women who have been to war — more than two million American men and women have deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan — when they themselves have not.

That reality is causing anxiety and unease at West Point.

How to do new things

The best way to learn something is to start doing it. Don’t wait for full knowledge to come to you. Often it won’t. Just pretend you know what you’re doing, and hit the walls. Make the problem small enough that you can start solving it right now, without waiting. Each part of the problem is smaller than the whole thing. And tell yourself you can do it, because you can.

Yep. Characteristic wisdom from Dave Winer, the guy who got me blogging all those years ago, and who continues to amaze and inspire people everywhere.

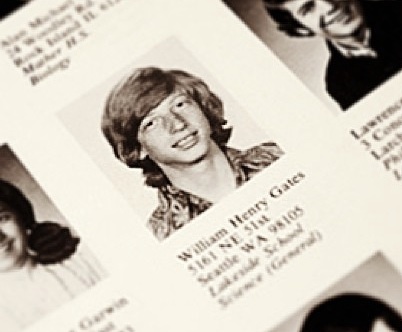

Freshman Bill

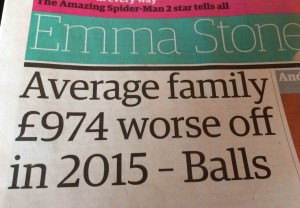

Fact or comment?

Partition blues

From J.K. Appleseed, writing in McSweeney’s:

How awesome would it be if you could partition your brain in the manner of a computer’s hard drive?

You could devote 7% of your brain to operate in foreign languages, 5% to cooking Italian food, 5% to knowing kung fu, and let’s say 23% to seduction techniques, just for starters. The sky’s the limit! Especially after you devote 5% of your brain to learning how to pilot a helicopter.

A modular brain would be so much easier to manage. You could selectively delete all unnecessary pop lyrics, reality TV show trivia, and the films of Zack Snyder. I would, however, suggest retaining the meta-memory of hating his movies, even though you no longer remember what they were, so as not to repeat your mistake. With the cleared up space, you could now set aside 5% for learning to play blues piano!

We’re only up to 50% at this point. The world of your brain is your oyster!

Right.

Meanwhile, your actual noggin is an undisciplined soup of useless details. You don’t remember where your car keys are, but you can’t get that stupid lick of Katy Perry’s “Roar” out of your head. You know the one. It goes, “Whoa, whoa! Oh, oh, oh, ohhh!”

Tony Blair’s Big Question

“Have you figured out how I can be on the right side of history without being on the wrong side of now?”

New Yorker cartoon showing a politician querying his staff.

Quote of the Day

“At times, the act of following Egyptian politics seems almost cruel — it’s like watching a lightning-fast sport played very badly, with every mistake reviewed in excruciating slow motion”.

Peter Hessler, The New Yorker, March 10, 2014