As someone who detests self-service checkout systems (why should the customer do all the work?), I was delighted to find a cartoon in the New Yorker showing a sign over the accursed terminals saying “NOT IN THE MOOD FOR HUMAN INTERACTION LINE”.

Category Archives: Asides

Networked echo chambers

Lots of people, including Cass Sunstein, have written about the gap between the Internet’s potential to become the greatest marketplace of ideas the world has ever seen, and the actuality, which is that most of us seem to prefer to operate inside digital echo chambers.

Nick Corasaniti thinks that use of the ‘Unfollow’ button on social media may be the way in which people now construct their own echo chambers.

With the presidential race heating up, a torrent of politically charged commentary has flooded Facebook, the world’s largest social networking site, with some users deploying their “unfollow” buttons like a television remote to silence distasteful political views. Coupled with the algorithm now powering Facebook’s news feed, the unfollowing is creating a more homogenized political experience of like-minded users, resulting in the kind of polarization more often associated with MSNBC or Fox News. And it may ultimately deflate a central promise of the Internet: Instead of offering people a diverse marketplace of challenging ideas, the web is becoming just another self-perpetuating echo chamber.

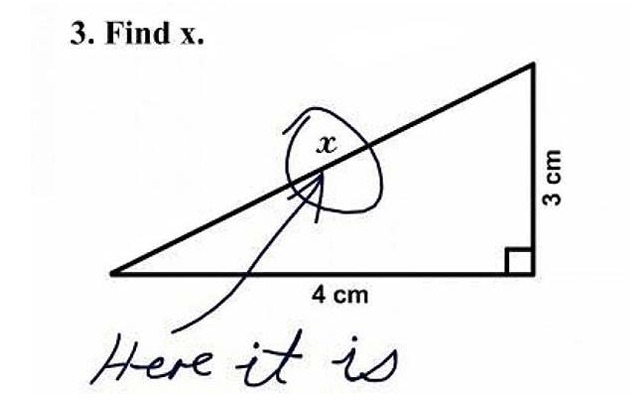

Sheer genius

This is lovely. From a compendium of ingenious answers to exam questions. Reminds me of the (probably apocryphal) story about Michael Frayn when he was a philosophy student at Cambridge. The story goes that one of the questions in a Part II paper read “Q2. Is this a question. Discuss.” To which he supposedly answered: “If it is, then this is an answer.”

Joke of the Day

“The Secret Service is the only law-enforcement agency that will get into trouble if a black man gets shot.”

American comedienne Cecily Strong at Saturday’s 2015 White House Correspondents’ Dinner.

Listen to Wikipedia

Wikipedia is one of the wonders of the world, which is why I donate to it as well as use and edit it. But until now I’d never thought of listening to the music that it makes.

Unmissable. Try it.

If I were an American undergraduate I’d say it was awesome, but now I discover that Wikipedia has no entry for that usage.

By Royal appointment

In her LRB review of Laura Thomson’s A Different Class of Murder: The Story of Lord Lucan, Rosemary Hill has an entertaining passage about two of Lord Lucan’s mates, Nicholas Luard and Dominick Elwes.

As the conventions of the 1950s loosened, hare-brained schemes were fashionable, though often doomed. The Establishment Club failed, taking Luard’s modest inheritance with it, and he and Elwes embarked on a succession of get-rich-quick enterprises. Their most entertaining failure was the retractable dog lead which Elwes patented. Since he and Luard were among the young men invited to dine (without wives) by Princess Margaret they thought she might be persuaded to use it when presenting prizes at Crufts to generate useful publicity. HRH agreed, but in front of curious photographers she put the spring-load on the wrong setting and all but strangled a chihuahua. Sales never recovered. Tellingly, the only Luard-Elwes venture to make money was their book, Refer to Drawer, a guide to confidence trickery.

That’s about par for the course for the rackety crowd of crooked or harebrained toffs who were Lucan’s playmates. In her review, Hill concludes that Lucan was not the murderer. I’m not convinced, and nor are some of the folks who have commented vigorously on the review.

Raymond Carr RIP

Raymond Carr, the great historian of modern Spain, has died at the ripe old age of 96. There will be lots of respectful obituaries like this one in the Guardian. I wonder, though, if they will capture the racy essence of the man. I’ve lost count of the number of people who knew him in Oxford, all of whom tell barely-credible stories of his various adventures, one involving coming upon him working as a waiter in a Swedish cafe, where he had come in pursuit of a woman.

He was also the model for the academic in Joseph Losey’s film Accident, in which Dirk Bogarde played a charismatic Oxford don.

Why this blog suddenly looks different

As you probably know, yesterday Google implemented its long-heralded algorithmic change to give more prominence to mobile-friendly sites in its search results. They also helpfully provided an online tool for checking whether one’s site was indeed ‘mobile friendly’ according to their criteria. So I ran the test on the previous version of this blog and — guess what? — it came out as being distinctly unfriendly. So there was nothing for it except to give it a facelift. Hence this new layout.

Arrogance, arrogance, dear boy. That’s the tech business for you

Intelligent filtering and insightful curation are rare arts. But Quartz is very good at them, which is why I read its daily dispatches the moment they arrive in my inbox.

I particularly like the Saturday edition, which comes with an elegant mini-essay by one of the editors.

Here is today’s, written by Leo Mirani:

For a decade, it seemed like the technology industry was going to usher in a newer, friendlier form of capitalism. The CEOs wore t-shirts and hoodies. Their staff had spare time to improve the world. They said they wouldn’t be evil. For a while, web users believed them.

But things have been shifting. This week, the European Union formally accused Google of abusing its dominant position in search. In India, Facebook is facing an uprising against Mark Zuckerberg’s internet.org, meant to give first-time users a taste of the internet for free. Uber is under criminal investigation in the Netherlands. Apple was last week met with underwhelming reviews for its watch.

Why? The uniting factor is arrogance. Google, with over 90% of the search market in Europe, blatantly favored its own services. Of the 500 million people who’ve used internet.org, first-time internet users make up only 1.4%, and Indians saw that this was less about connecting the poor than consolidating Facebook’s dominance. Apple decided to make the watch without any notion of what it might actually be used for—except maybe as a notifications device. No wonder even people who wanted to like it had a hard time recommending it.

The ultimate symbol of that arrogance, of course, is tech company valuations. The latest example is Slack, a one-year-old chat tool for businesses, whose funding round this week prompted cries of disbelief. “Is Slack Really Worth $2.8 Billion?” asked the New York Times (paywall). “It is, because people say it is,” said the CEO.

Of course he’s right, in a sense: Markets, not tech company founders, determine what their companies are worth. But when founders conflate market value with true value, they start to think they can do no wrong. That’s where their downfall begins.

Osborne’s car-crash interview

Fascinating. Who would have thought it of Marr — normally a relatively soft-soap interviewer? This one will join Paxman’s celebrated exchange with Michael Howard all those years ago.

Interesting also that there are structural similarities between the two interviews. I wonder if Marr decided to follow the Paxman template.

What’s also very interesting is the astute use that Labour has made of the interview video. They edited it cleverly and then posted it on Facebook.

Thanks to Tom for the original link.