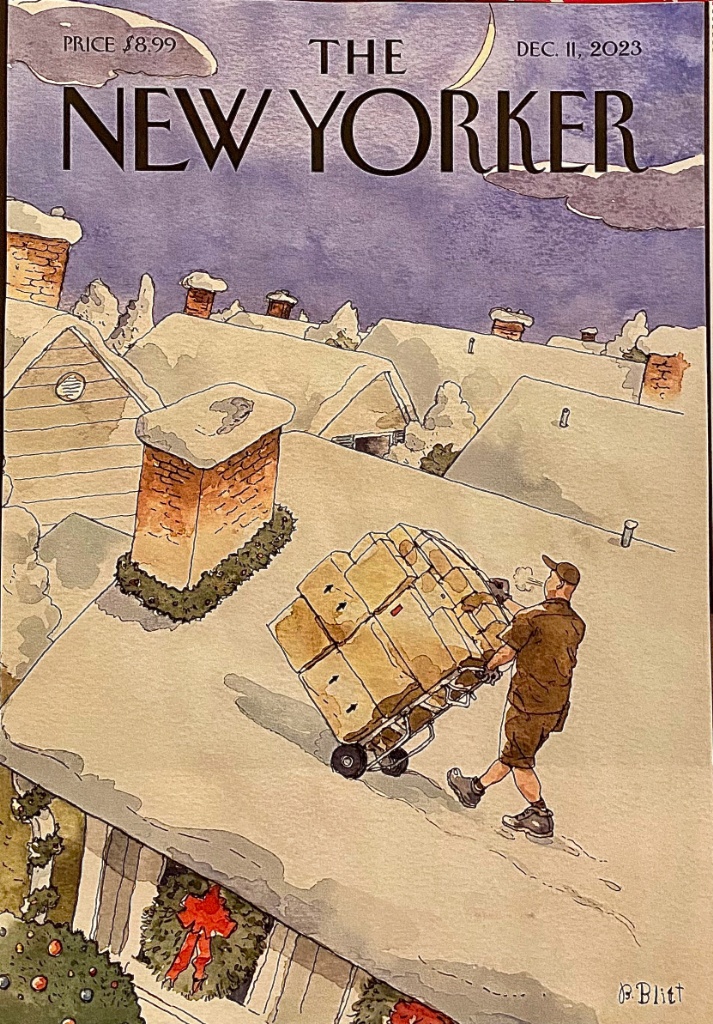

Vernacular architecture, English style

Somewhere in Cambridgeshire

Quote of the Day

”One afternoon, when I was four years old, my father came home, and he found me in the living room in front of a roaring fire, which made him very angry. Because we didn’t have a fireplace.”

- Victor Borge

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Morten Lauridsen | O Magnum Mysterium | Nordic Chamber Choir

Amazingly serene.

Long Read of the Day

Davos: high altitude, low impact

Lovely sardonic essay by Elise Labott on the ludicrous gabfest in Davos.

In the frost-kissed town of Davos, where the world’s glitterati converged this week for the 54th annual World Economic Forum under the guise of shaping the world’s future, something sounded thinner than the altitude: It was the air of relevance, of touch with the terra firma where the rest of us reside.

The forum has always been a curious blend of intellectual masturbation and disconnect from ground truths. We’ve all heard the long-running jokes pointing out how billionaires and politicians arrive in private jets to discuss carbon footprints. Now they speak of AI’s societal impacts while their companies quietly lobby against regulations that could curb their techno-empires…

Great stuff and an entertaining read. I’ve only been to Davos once — in the Summer of 1978, when I was on a walking holiday in Switzerland. I remember it as a sleepy and rather dull town in which I bought a Swiss army penknife (which I still possess) and a walking stick. I’ve never understood the lure that the gabfest has for journalists who should know better.

What’s in store if the IPA (Amendment) Bill becomes law

Yesterday’s Observer column

Which brings us to the investigatory powers (amendment) bill, which is now before their lordships in Westminster. “The world has changed,” says the blurb. “Technology has rapidly advanced, and the type of threats the UK faces continues to evolve.” The new bill will “enable the security and intelligence agencies to keep pace with a range of evolving threats, against a backdrop of accelerating technological advancements that provide new opportunities for terrorists, hostile state actors, child abusers and criminal gangs”. And, of course, for this is global Britain, “the world-leading safeguards within the IPA will be maintained and strengthened”.

Quite so. But upon closer inspection, the proposed means to those laudable ends do not exactly inspire confidence. For example, the bill proposes that the security services should have much more latitude in building and exploiting so-called “bulk datasets of personal information”, ie data about individuals who “have a low or no expectation of privacy”. This could allow the collection and use of CCTV footage, or the 20bn facial images scraped from the internet by Clearview, on the grounds that those of us who appear in such datasets have “no expectation of privacy”…

Do read the whole thing .

Books, etc.

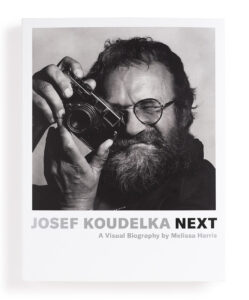

I’m reading Melissa Harris’s intriguing ‘visual biography’ of the great photographer Josef Koudelka and am entranced by it.

Here’s a typical passage describing how Markéta Luskakova first met him at a dinner hosted by a mutual friend, Jirí Chlíbec.

Luskacova’s first impression of Koudelka was of a “very high-spirited young man”. Later, as they were drinking wine, Chlíbec mentioned that his friend was not only an aeronautical engineer, but also a photographer. Luskacova told me: “Meeting Josef in January 1963, felt like a godsend. She turned to him: “‘Listen, you should teach me photography.’ He said: ‘Nobody can teach you photography. You either see or you don’t see.’ I said: ‘Josef, I don’t want you to teach me to see, I want you to teach me where to press what.'” Koudelka laughed, and agreed.

They met the next day. Along with a camera, Koudelka brought a small piece of paper for Luskacova, on which he had written directions for various photographic opportunities, and their optimum exposures, depending upon the sunlight, cloud, coverage, and so on (she still has this slip of paper). Luskacova pointed out that he had not written any instructions for full sun. He responded: “When there is full sun, lie in it, enjoy it – and don’t take pictures.” Apparently there was, she began to understand, a rule for everything.

Luskakova went on to become a distinguished photographer herself.

Linkblog

Something I noticed, while drinking from the Internet firehose.

- Megan McArdle’s ’12 Rules for Life’ Link

I particularly liked #2:

Politics is not the most important thing in the world. It’s just the one people talk about the most. That’s because everyone shares the government; only you are married to your spouse, and can knowledgeably expound on their habit of mashing up soft-boiled egg and ketchup into a disgusting paste; this makes it hard to have much of a dialogue with your friends on the subject.

But your spouse and others around you matter more to your happiness than the government does. You will notice, as you go about your day, that many, many important things are riding on your spouse, things that will have immediate costs and benefits to you. Very few of the things that irritate you or bring you joy have anything to do with the government. So keep some perspective about politics. It doesn’t matter as much as the real people around you, and the real things you can do in the world. If you have to choose between politics and a friendship, choose the friendship every time.

Reminds me of E.M. Forster’s memorable dictum (in What I Believe and Other Essays): “If I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country.”

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 6am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!