Hmmm… On the basis of this trailer I’m not sure it’ll be worth the journey. It looks like famous-director-who-knows-nothing-about-the Net goes round talking to famous geeks who blind him with tech and say silly things.

Category Archives: Asides

How the tech industry differs from the automobile business

Reading a fascinating WashPo interview with Apple’s CEO, Tim Cook, I was struck by this:

We’re a bit larger today, so we can do a bit more than we could do 10 years ago or even five years ago. But we still have, for our size, an extremely focused product line. You can literally put every product we make on this table. That really is an indication of how focused it is. I think that’s a good thing. Regardless of who you are, there’s only so many things that you can do at a very high-quality and deep, deep level — personally and in business. And so we’re not going to change that. That’s core to our model and way of thinking.

This seems very different to the way most successful modern companies operate. With them, the game appears to be to provide a product to match every discernible market niche.

Take Mercedes, for example. I’m perpetually baffled by the various Mercedes model I see on our roads. So I went to the company’s site to try and get a handle on the range.

Here’s what I found. Mercedes sell 28 different types of consumer vehicle in the UK (I’ve ignored the commercial stuff), to wit:

- 3 types of hatchback

- 4 types of saloon

- 4 types of estate car

- 6 different coupés

- 4 different models of cabriolet/roadster

- 6 SUV models

- 1 MPV

My guess (I haven’t checked) that the BMW range is just as diverse/confusing. It must be a hell of a challenge to maintain some level of coherence in this profusion. How do Mercedes sales personnel keep up? Maybe they instantly categorise every customer who comes in the door. As in: Here comes an estate-car customer. Oh, bet she’s a coupé type. He’s definitely S-class material. And so on.

Maybe the contrast between Mercedes and Apple is emblematic of the cultural differences between the tech and the auto industries. In that sense, Elon Musk’s approach to the Tesla range seems much closer to Apple’s.

Bloomsday

Today is Bloomsday — the day when Joyce enthusiasts all over the world celebrate Ulysses. In my case, I always host a Bloomsday lunch in which guests drink red Burgundy and eat Gorgonzola sandwiches. Why? Because that’s what Leopold Bloom had when he lunched in Davy Byrne’s pub, taking a break from his perambulations around Dublin.

This year’s lunch was special because one of the guests was an old friend, Dr Vivien Igoe, who is one of the foremost experts on Joyce’s connections with his native city. Her new book, The Real People of Joyce’s Ulysses came out last week, and throws a fascinating light on Joyce’s powers of observation and imagination.

We’ve always known that most of the hundreds of characters in Ulysses were drawn from real people, and many of them appear under their own names in the pages of the novel. But who were they, really? Now we know, thanks to an extraordinary piece of scholarship.

Theresa May-Machiavelli

This morning’s Observer column:

So Theresa May’s investigatory powers bill has completed its passage through the House of Commons. It passed its third reading by 444 votes to 69 and now goes to the Lords for further consideration. Their lordships will do their best – and they are good at scrutinising complex legislation – but sometime in the next parliamentary session the bill, substantially unchanged, will receive the royal assent and become law. As a result, the powers of the national security state will have been significantly expanded.

As an example of legislative cunning, the bill is a machiavellian masterpiece…

The interesting case of the Internet’s ‘i’

The AP style book now says that the Internet should no longer be capitalised.

Vint Cerf, the co-designer of the network, disagrees.

The editors at AP fail to understand history and technology,” Cerf told Politico on Wednesday (June 1). His beef is that there has always been a line between the public internet and a private internet that has no connection to the outside world, although it shares the same TCP/IP protocols. This, he warns, is simply daft. “By lowercasing you create confusion between the two and that’s a mistake,” he wrote.

I agree.

Just one (more) Cornetto

Venice, Friday.

I never see a gondola without thinking of that ludicrous (but very funny) ad for Cadbury’s Walls Cornetto ice-creams. On my first visit to Venice, years ago, I was walking along an alleyway when I heard someone singing ‘O Solo Mia’ in the distance. I came round a corner, found myself at a canal and there was a gondolier singing to his American tourist clients as he punted them round the city. For a moment, I thought I must be hallucinating. But it was real: parody made flesh.

The guy on Friday wasn’t singing. Mercifully.

Larger version here.

A Prime Minister who knows about quantum computing. Whatever next?

I’ve been idly thinking about how David Cameron (or, for that matter, Boris Johnson) would answer such a question.

Transparency, non! (If you’re M. et Mme Piketty, that is)

Well, well. This from Frederic Filloux about the leading French public intellectual, Julia Cagé (of whom, I am ashamed to say) I had never heard.

Last year, she published a book titled Sauvez Les Medias, capitalisme, financement participatif et démocratie. The short opus collected nice reviews from journalists traumatized by the sector’s ongoing downfall and eager to cling to any glimmer of hope. Sometimes, though, the cozy entre nous review process goes awry. This was the case when star economist Thomas Piketty published a rave book review in Libération, but failed to acknowledge his marital tie to Julia Cagé. In fact, Piketty imposed the review on Libération’s editors, threatening to pull his regular column from the paper if they did not oblige, and then refused to disclose his tie to Mrs Cagé; rather troubling from intellectuals who preach ethics and transparency.

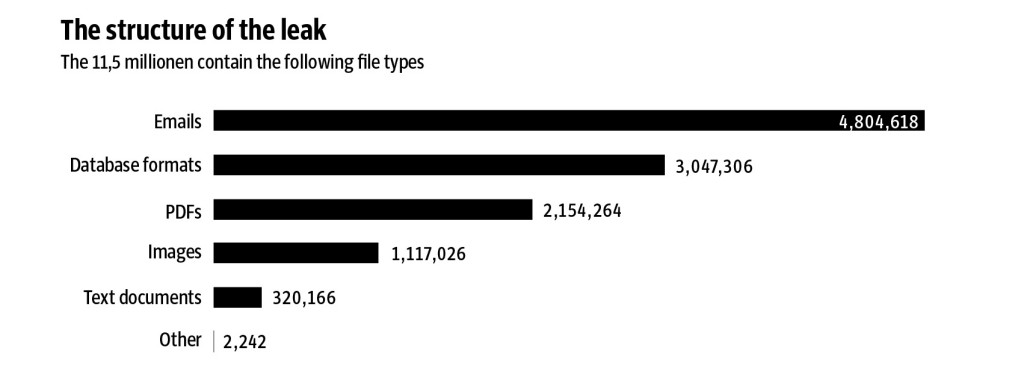

The scale of the Panama papers data trove

Apart from anything else, the Panama papers project represents a triumph of data handling and intelligent use of software tools. Also good project management in distributed, collaborative working — in apparently total secrecy. If it weren’t an international effort it would be Pulitzer prize material.

Steve Jobs: genius loci

In a Time Magazine report on Apple’s battle with the FBI over the unlocking of the San Bernardino killer’s iPhone 5c, I was struck by this passage:

At 55, Cook is wiry and silver-haired, with an Alabama accent that he has carefully transplanted to Silicon Valley. We spoke in his office at Apple’s headquarters in Cupertino–the address, famously, is 1 Infinite Loop. It’s a modest office, an askew trapezoid, almost ostentatiously unostentatious, with a few framed “Think Different” posters on the walls, some arty photographs of Apple stores and a large wooden plaque with a quote from Theodore Roosevelt on it (the “daring greatly” one). Jobs’ office is next door. It’s dark, with curtains drawn, but the nameplate is still there.

Another source adds some detail:

The Apple cofounder passed away from cancer in October 2011, and his successor decided to keep his office as a form of memorial. According to Cook, there are even drawings on the whiteboard that Jobs’ children drew.

There’s something deeply touching about this, not least because Tim Cook offered Jobs part of his own liver in the hope that it might have averted his death. But keeping his office untouched is a recognition of the extent to which the spirit of the company’s co-founder pervades the place still.

He’s still the genius loci — the protective spirit of the place. Which makes one wonder what they will do with the office when Apple moves to its new corporate HQ in the Autumn.