Light and Shade

Quote of the Day

”Winning isn’t everything, but wanting to is.”

- Arnold Palmer (who won the Masters four times, the PGA Championship three times, the US Open in 1969 and the British Open twice)

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Keith Jarrett | My Song | 1978

Long Read of the Day

Claims That AI Productivity Will Save Us Are Neither New, nor True

Not only does new tech often result in more work for people, says Elizabeth Renieris, but it also introduces additional kinds of work.

Simply put, the AI productivity narrative is a lie. It holds that by automating tasks, AI will make them more efficient and make us, in turn, more productive. This will free us for more meaningful tasks, or for leisurely pursuits such as yoga, painting or volunteerism, promoting human flourishing and well-being. But if history is any guide, this outcome is highly unlikely, save for a privileged elite. More likely, the rich will only get richer.

Because it’s not technology that can liberate us. To preserve and promote meaningful autonomy in the face of these AI advancements, we must look to our social, political and economic systems and policies. As Derek Thompson observes in The Atlantic, “Technology only frees people from work if the boss — or the government, or the economic system — allows it.” To allege otherwise is technosolutionism, plain and simple.

Yep. ‘AI’ may indeed lead to increased productivity, which could be a good thing. But only if the profits from that are equitably shared. Which they are not at the moment — and if tech corporations have their way, never will be.

Regulating crypto

Dave Birch (Whom God Preserve) pointed me to Nicholas Weaver’s White Paper, The Death of Cryptocurrency. It’s an interesting, incisive essay, which comes to admirably succinct conclusions, as follows:

Regulators, especially regulators in the United States, often fear accusations of stifling innovation. As such, the cryptocurrency space has grown over the past decade with very little regulatory oversight.

But fortunately for regulators, there is no actual innovation to stifle. Cryptocurrencies cannot revolutionize payments or finance, as the basic nature of all cryptocurrencies render them fundamentally unsuitable to revolutionize our financial system — which, by the way, already has decades of successful experience with digital payments and electronic money.

The supposedly “decentralized” and “trustless” cryptocurrency systems, both technically and socially, fail to provide meaningful benefits to society — and indeed, necessarily also fail in their foundational claims of decentralization and trustlessness.

When regulating cryptocurrencies, the best starting point is history. Regulating various tokens is best done through the existing securities law framework, an area where the US has a near century of well-established law. It starts with regulating the issuance of new cryptocurrency tokens and related securities. This should substantially reduce the number of fraudulent offerings.

Similarly, active regulation of the cryptocurrency exchanges should offer substantial benefits, including eliminating significant consumer risk, blocking key money-laundering channels, and overall producing a far more regulated and far less manipulated market.

Finally, the stablecoins need basic regulation as money transmitters. Unless action is taken they risk becoming substantial conduits for money laundering, but requiring them to treat all users as customers should prevent this risk from developing further.

Comes like a breath of fresh air. If only we had the same for ChatGPT. (Thinks: now there’s an idea.)

Books, etc.

I’d been reading Clive James’s essay on Stefan Zweig in his magnum opus, Cultural Amnesia.

“Zweig’s own achievements,” James writes,

are nowadays often patronised: a bad mistake, in my view. Largely because of his highly schooled but apparently effortless gift for a clear prose narrative, he attained, while he lived, immense popularity not just in the German-speaking countries but in the world entire, and he is still paying the penalty for it. Except in France, where his major works are never out of print, it is usually safer to call him second-rate. Safer, but not sound.

I decided it was high time I read some Zweig. So I downloaded a copy of The World of Yesterday: Memoirs of a European and embarked upon it. And goddam it, Clive was right.

My commonplace booklet

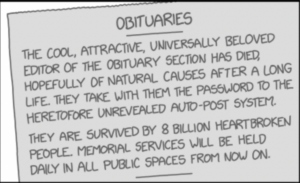

“”There has been much hand-wringing about ChatGPT and its ability to replicate some composition tasks. But ChatGPT can no more conceive “Mrs. Dalloway” than it can guide and people-manage an organization. Instead, A.I. can gather and order information, design experiments and processes, produce descriptive writing and mediocre craftwork, and compose basic code, and those are the careers likeliest to go into slow eclipse.”

- Nathan Heller in “The End of the English Major”

This Blog is also available as a daily email. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!