Electioneering circa 1755

‘Chairing the Member’ (from Hogarth’s The Humours of an Election series of 1754-55).

Quote of the Day

“So let’s give another big tax cut to the super-rich. That’ll teach bin Laden a lesson he won’t soon forget.”

- Kurt Vonnegut

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young | Ohio

A song written after the Kent State Shootings

Long Read of the Day

Who is Britain’s next Prime Minister?

Judicious essay by Tim Garton Ash on Keir Starmer, the Labour leader and putative Prime Minister if the election goes as predicted by opinion polls.

Sample:

The conservative columnist Daniel Finkelstein knew him when he was young, through a friend who was a member of the East Surrey Young Socialists – a groupuscule title that, for anyone who knows Surrey, feels almost like a contradiction in terms. (Finkelstein’s article behind paywall, I’m afraid begins with the arresting line ‘I was sitting in a kitchen above a brothel on the Archway Road when I first heard the name Keir Starmer.’) He recalls a young Starmer who was very much on the left, supporting the miners’ and other unions in strikes, helping to produce ‘a Marxist magazine’ and calling for a united Ireland.

So how come this lifelong ‘left liberal’ (Finkelstein’s term) is now advocating policies so much to the centre, and even with touches of centre-right on issues like migration and tax? After going through a number of hypotheses, Finkelstein reaches a verdict that is extremely creditable to the Labour leader. Starmer is ‘someone with a left-wing instinct,’ but also pragmatic and deeply realistic, which ‘leads him again and again to temper his initial view’. He is, the conservative columnist concludes, ‘open-minded and careful and deliberative. He is someone I will disagree with, I’m sure. But also respect.’ A cynic might say that the journalist has assured himself good access to the next occupant of No. 10 Downing Street. But knowing Finkelstein, I think this qualified tribute is worth a lot more than that…

Over the last few years I’ve been irritated by the view that younger, liberal- or left-leaning friends and colleagues have of Starmer — that he’s “dull”, “boring” or “uninspiring”. Even Tim Garton Ash briefly lurches into that territory when he writes that Starmer has “all the charisma of a bank manager”. (Remember bank managers? Me neither.) But he also notes his “achievement in bringing the Labour party back from the unelectable hard left of Jeremy Corbyn to the verge of what looks like a big, possibly even a landslide victory”.

For me, the historical figure that Starmer brings to mind is Clement Attlee, the Labour leader who won a landslide victory in 1945 and led a government that really transformed Britain. People also regarded Attlee as dull and lacking charisma. Winston Churchill described him as “a modest man who had much to be modest about”, a wisecrack that conveniently distracted attention from the fact that Attlee had run the country during the way, thereby freeing Churchill to do his stuff. And he got stuff done, which is what the benighted Disunited Kingdom needs just now.

I also like his riposte in verse to those who had underestimated him:

There were few who thought him a starter,

Many who thought themselves smarter.

But he ended up PM, CH and OM,

an Earl and a Knight of the Garter.

What the election is really about

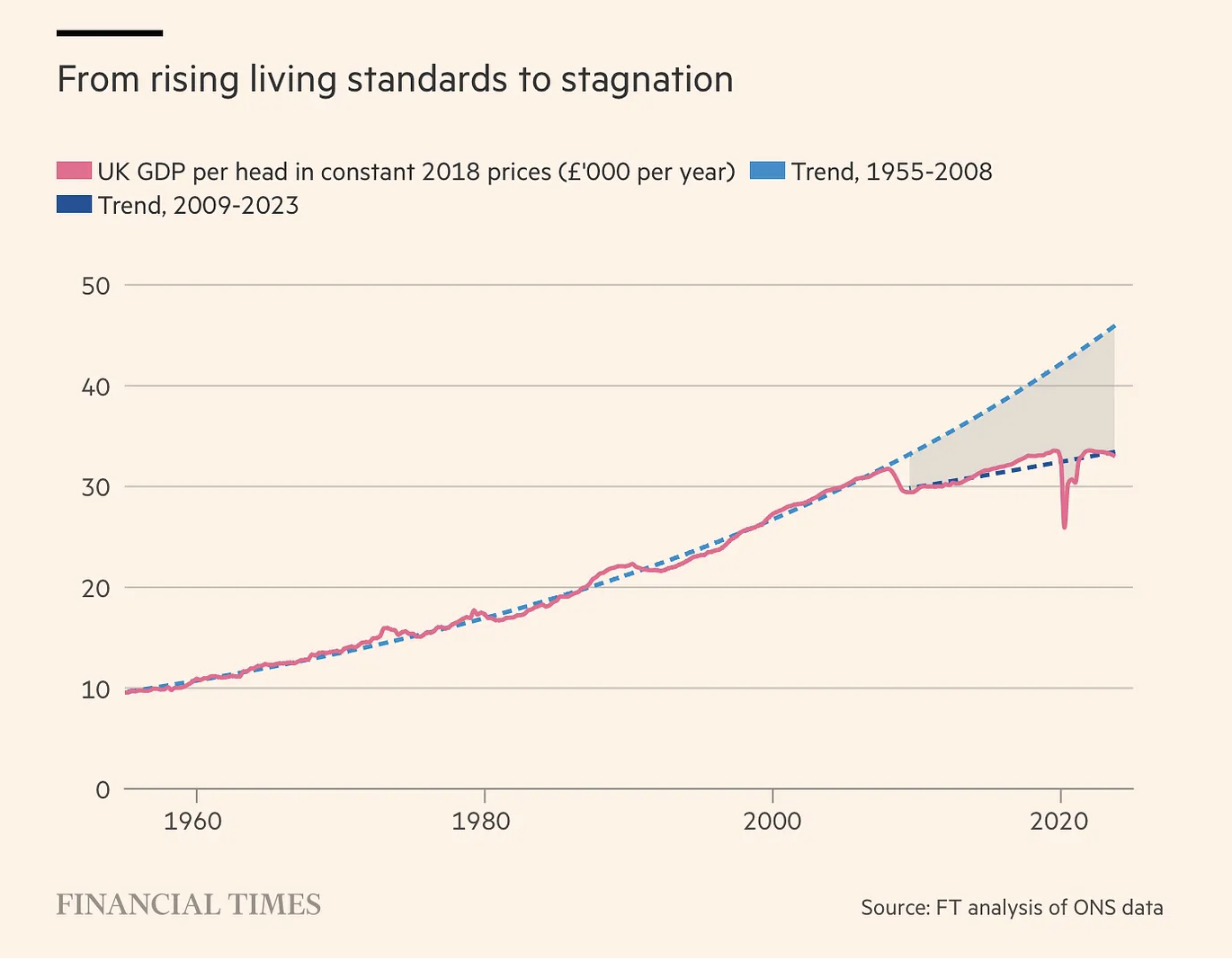

This chart from the Financial Times puts it in a nutshell.

As Andrew Curry (Whom God Preserve) observes on his Substack,

What it shows is that after 2008, or so, the British economy fell off the track of the rate of growth that it had been on for the previous 50 years, and jumped to another track.

That trend line from 1960-2010 had not been particularly compelling—it was still slower than other comparable economies—but it did trend upwards.

The best single explanation of this is the austerity policies that the Cameron-Osborne led Coalition government chose to follow, ostensibly to deal with the level of government debt incurred in dealing with the financial crisis.

There are different versions of why they opted for this…

There are. One (not mentioned by Andrew) is the ludicrous narrative foisted on a credulous British public by George Osborne (the Chancellor and the brains behind the Cameron government) that the huge sovereign debt run up the the Brown administration to bail out the banks was in fact just a typical example of Labour profligacy — so that, just as households who run up too much debt must eventually tighten their belts, so too must the UK.

The ‘explanation’ highlighted by Andrew is more bizarre; it is that

Osborne saw a presentation by Reinhart and Rogoff [two distinguished American economists] of their 2010 research paper that said that when debt climbed above 90% of annual GDP it choked off growth. This is, of course, the research paper that has the most famous spreadsheet error in economics history.

The error was that in their Excel spreadsheet,

Reinhart and Rogoff had not selected the entire row when averaging growth figures: they omitted data from Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada and Denmark. In other words, they had accidentally only included 15 of the 20 countries under analysis in their key calculation. When that error was corrected, the “0.1% decline” data became a 2.2% average increase in economic growth.

So the key conclusion of a seminal paper, which had been widely quoted in political debates in North America, Europe Australia and elsewhere, was invalid.

Andrew points out that although the error was exposed in 2013, that Osborne did not change policy as a result. Which suggests that his rational for austerity was always purely ideological — the product of an obsession with shrinking the state.

In doing that he also shrank the economy. And the impact of his austerity programme — which, among other things, has brought many UK local authorities to the brink of bankruptcy (and every road in the UK pitted with pot-holes) — probably influenced the Brexit vote, with all the resulting economic havoc that has caused.

All of which implies that the damage the Conservative government has done to the UK goes back almost to the beginning of its reign, and predates even the chaos of the May-Johnson-Truss-Sunak era.

The trouble is that it’s not clear that the incoming Labour crowd understand this. They are still mentally trapped in the Osborne household-budget analogy. Which is what leads Andrew Curry to observe, at the end of his blog post, that “People keep telling me that neoliberalism is dead, but its cold bony hand is still gripped tight around the imaginations of our political class.”

It is.

Linkblog

Something I noticed, while drinking from the Internet firehose.

- How Election Night will play out. Useful timeline from the Guardian. Personally, I’ll just wait for the Exit Poll — shortly after polls close at 10pm — and then try to get a night’s sleep.

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 6am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!

I’ve been dipping in and out of

I’ve been dipping in and out of