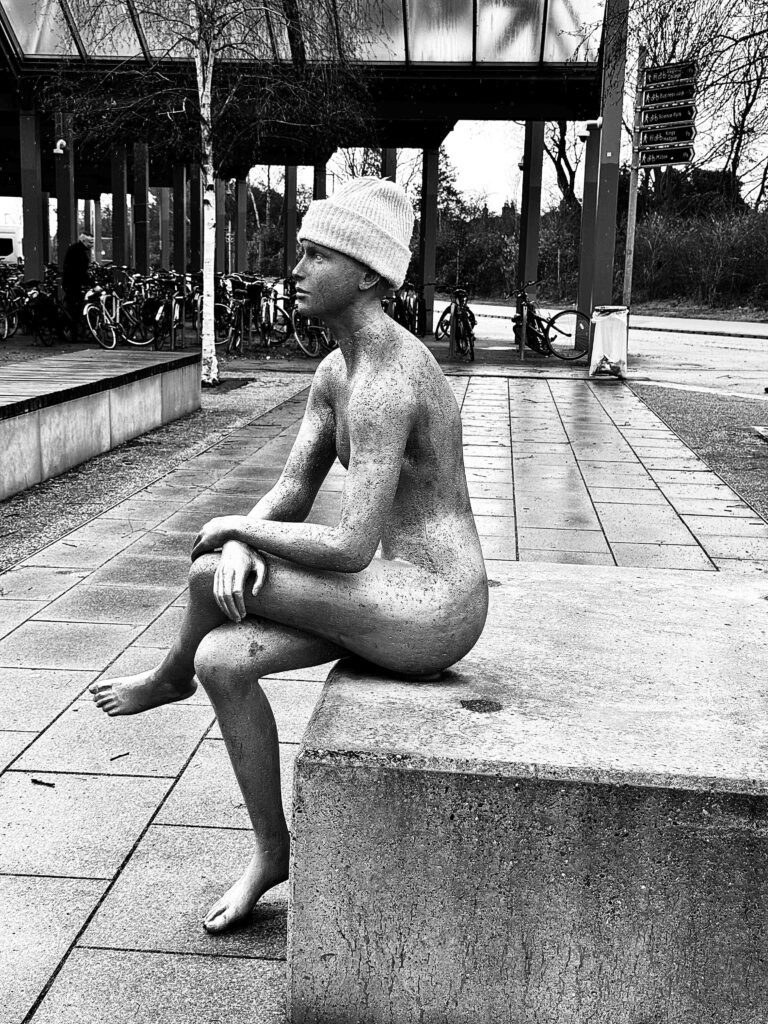

Outside the British Museum

On a wet morning.

Quote of the Day

”One wonders in these places why anyone is left in Dublin, or London, or Paris, when it would be better, one would think, to live in a tent or hut with this magnificent sea and sky, and to breathe this wonderful air, which is like wine in one’s teeth.”

- John Millington Synge on the Kerry countryside.

Whenever I’m in Kerry, I know just what he meant.

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Handel| As steals the morn (L’Allegro, HWV 55) | Amanda Forsythe & Thomas Cooley, Voices of Music

Staggeringly beautiful aria. Good way to start the day.

Long Read of the Day

The Artist’s Reward

In these horrible times, we occasionally need something uplifting to read. So here is something that I think merits that label — Dorothy Parker’s profile of Ernest Hemingway, published in the New Yorker on 23 November, 1929.

Here’s a sample:

I have heard of him, both at various times and all in one great bunch, that he is so hard-boiled he makes a daily practice of busting his widowed mother in the nose; that he dictates his stories because he can’t write, and has them read to him because he can’t read; that he is expatriate to such a degree that he tears down any American flag he sees flying in France; that no woman within half-a-mile of him is a safe woman; that he not only commands enormous prices for his short stories, but insists, additionally, on taking the right eye out of the editor’s face; that he has been a tramp, a safe-cracker, and a stockyard attendant; that he is the Pet of the Left Bank, and may be found at any hour of the day or night sitting at a little table at the Select, rubbing absinthe into his gums; that he really hates all forms of sport, and only skis, hunts, fishes, and fights bulls in order to be cute; that a wound he sustained in the Great War was of a whimsical, inconvenient, and inevitably laughable description; and that he also writes under the name of Morley Callaghan. About all that remains to be said is that he is the Lost Dauphin, that he was shot as a German spy, and that he is actually a woman, masquerading in man’s clothes. And those rumors are doubtless being started, even as we sit here.

Hemingway; people are so eager to hear that you haven’t the heart to send them away empty. Young women, in especial, are all of a quiver for information. (Sometimes I think that the wide publication of that smiling photograph, the one with the slanted cap and the shirt flung open above the dark sweater, was perhaps a mistake.)

“Ooh,” they say, “do you know Ernest Hemingway? Ooh, I’d just love to meet him! Ooh, tell me what he’s like!”

Well, I warned you the task sinks me…

Do read on. And while you’re at it, crack open that bottle of Absinthe you’ve been hiding away.

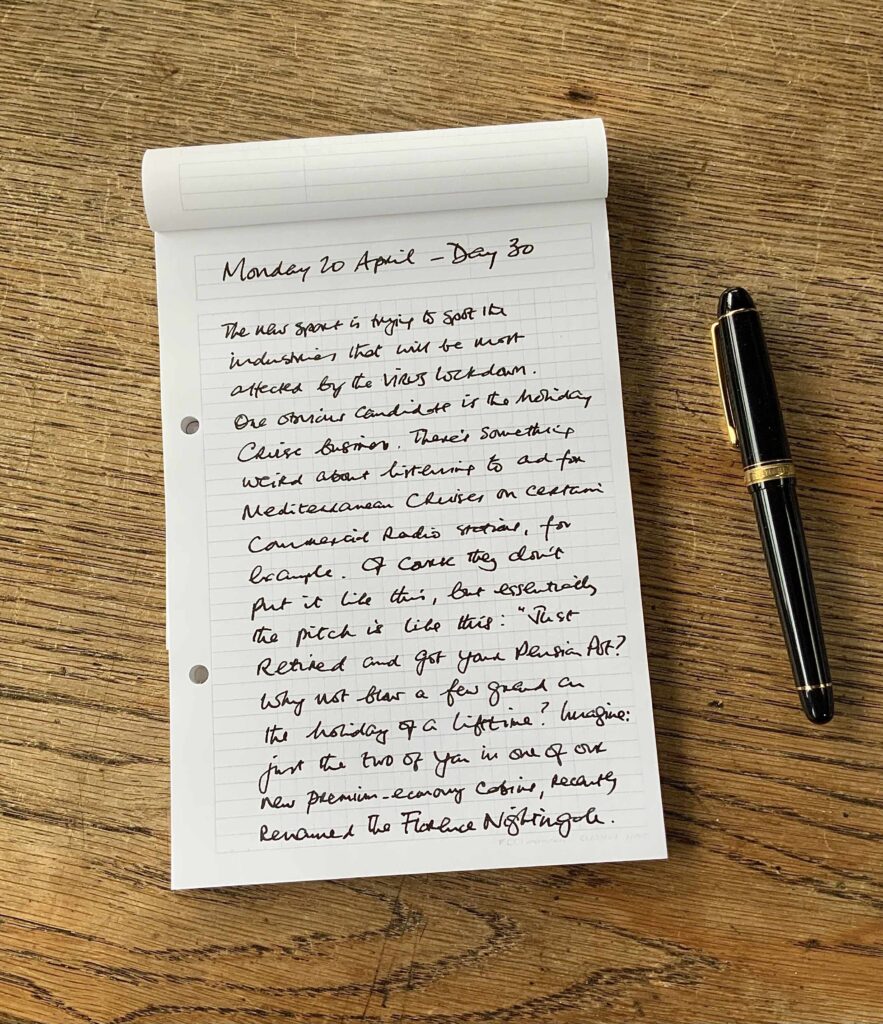

My commonplace booklet

One of the infuriating things about living in Britain at the moment is having to watch a Labour Party which has a huge parliamentary majority without, it seems, the faintest idea of what to do with it. Jonty Bloom had a fine blast about this yesterday.

Being forced by your own back benchers to be nicer to the poor is one thing, but to introduce a perfectly fair reform to the inheritance tax system and then give concessions to whinging farmer is another, the same with pubs.

Being kicked by the tabloids is one thing but allowing them to kick you about is another and habit forming. The more concessions and back downs, the more the pressure from every lobby group and dodgy cause grows because they know pressure works.

If Labour and Sir Kier are to turn this around they need to find some radical policies and force them through.

Far too many things are just being kicked down the street when ministers should be forcing them through parliament. Reforming the police for instance, or hiking defence spending now, or regulating the media better. Do it now and don’t back down, ever.

My own personal suggestion would be taking on the trade unions, the middle class trade unions that is, the ones that hike prices for us all, are closed shops and often farcically incompetent and useless.

Dentists, vets, lawyers, chartered surveyors and auditors just for a start. All charge far too much, add to our cost of living, try to ban competition and keep out new entrants.

How about some real competition, and some real capitalism?

Amen to that. Especially the dentists and vets.

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 5am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!