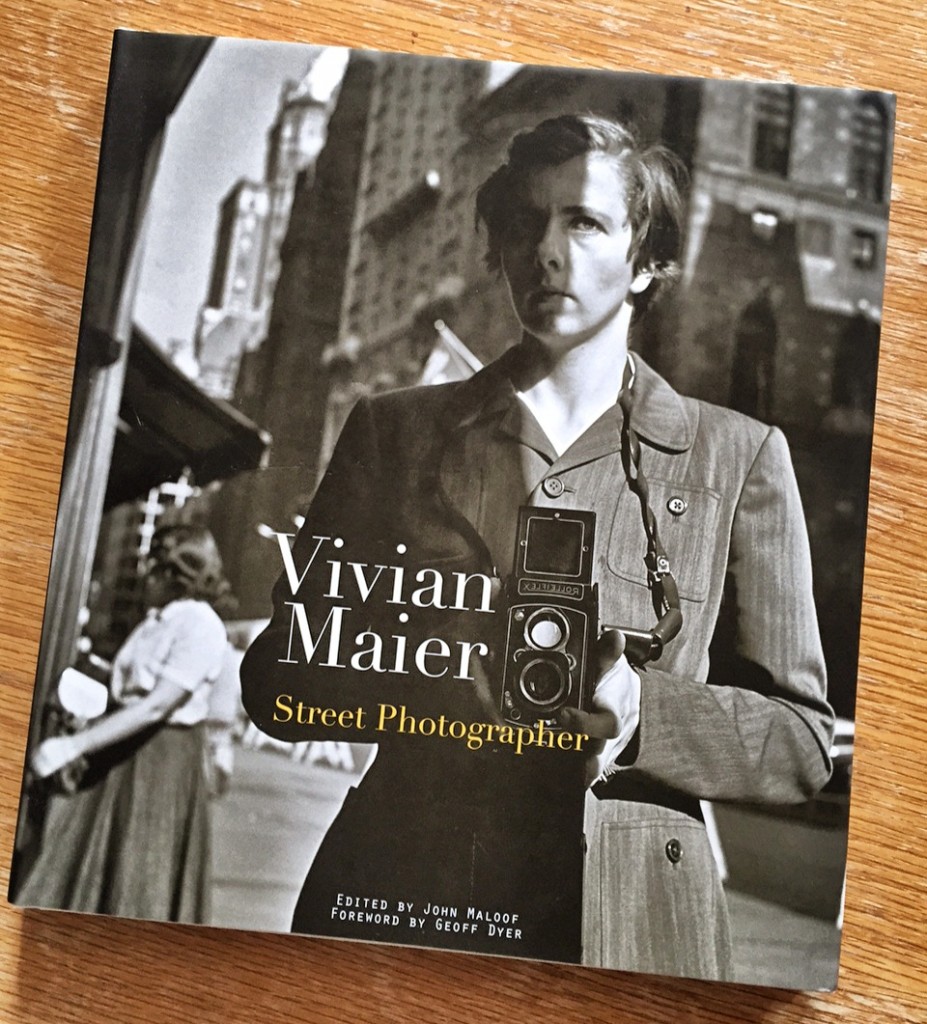

Vivian Maier was one of the great street photographers of our time — as a visit to VivianMaier.com or a dip into this beautiful book will confirm. She was possibly also the most mysterious photographer who ever lived, and all her fame is posthumous because of the remarkable efforts of John Maloof, who stumbled on her work after buying a box of negatives at a public auction and who has since done an amazing job of rescuing and publicising her work.

Vivian Maier was a nanny who lived and worked in Chicago for over four decades. On her days off — and on the days when she was caring for kids — she always carried a camera (a Rolleiflex) with which she recorded the streetscape of the North Shore of Chicago. In her lifetime she took 150,000 photograph which cumulatively provide one of the most comprehensive visual visual record of urban life in mid-20th-century America. And the strange thing is that nobody knew: she never published her work, and doesn’t seem to have shown it to anyone. She died in 2009, a lonely and solitary figure, an unknown genius.

I’ve just watched a terrific documentary — Finding Vivian Maier — made by John Maloof and Charlie Siskel which tells the story of Maloof’s painstaking quest to uncover Maier’s identity and piece together the story of her troubled and puzzling life.

It’s an amazing story which leaves one with two thoughts. The first is that to be a great artist one needs to have — in Graham Greene’s words — “a sliver of ice” in one’s heart. Maier’s photographs of the people she encountered on the streets of Chicago are often unflinching (though not heartless) photographs of people in distress or under stress. And Maloof’s revelations of her reclusive personality and strange obsessions (she was an Olympic-class hoarder of newspapers, for example) suggest someone who had been damaged in some way by experiences in her early life.

The other thought is a reflection on what a remarkable camera the Rolleiflex was. The technical quality of Maier’s images (as the prints in the book show) are often stunning. Those Zeiss Planar and Schneider Xenotar lenses were — and are still (I’ve got one) — superb.

But also the fact that it was a twin-lens reflex camera meant that she was looking down into the viewfinder rather than interposing the camera between her and the subject and this enabled her to focus and frame the shot, and then to maintain eye-contact with the people whose lives she was recording while she pressed the button.