The Irish Times had a nice piece about the new exhibition of Robert Doisneau’s photography currently in show at the Cartier-Bresson Foundation in Paris. (Memo to self: check out Eurostar prices.) It rather undermines the image of Doisneau as a frivolous, romantic street photographer.

He captures the chalky, lonesome feel of the postwar industrial suburbs that were then rising fast on the capital’s periphery – brutalist towers, shantytown huts, oppressive grey skies, factory plumes rising in the distance. Workers file out in silhouette from the giant Renault plant at Boulogne-Billancourt, where Doisneau worked for five years. A faceless cyclist, his head cast downward, hurries home through the heavy rain. In Carrefour Saint-Germain (1945), the famously elegant cross-roads at the heart of Paris is under heavy snow, transforming it into an anonymous eastern European esplanade. During the second World War, Doisneau printed pamphlets and fake identity papers for the resistance, and here there are constant reminders of the war: Le cheval tombé (1942), an image of a fallen horse lying on a wet Parisian street as a crowd watches helplessly, represented for Doisneau “the great sadness” of his city under the Nazi occupation.

And yet familiar Doisneau signatures abound: the banality of daily toil brightened by a knowing, ironic juxtaposition, a belly-laugh, a stolen smile or – a recurrent theme – the escape routes dreamed up in a child’s imagination. And so, in La voiture fondue (1944), five children turn the clapped-out shell of an abandoned car into a sumptuous carriage, the coachman with his whip on the roof, another navigator on the bonnet, a third boy keeping a vigilant eye on the road behind.

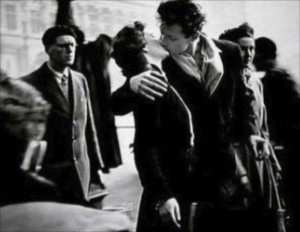

But in a way the most interesting thing about the piece is a box about his most famous photograph — Le Baiser de l’Hotel de Ville.

I’ve seen that picture hundreds of times — and wondered if it had been staged.

A few years before Doisneau’s death in 1994, a retired couple came forward claiming they were the lovers featured in the photo and should be paid their share of the royalties. The case was dismissed, but in the course of it Doisneau revealed that the scene had been staged. While working on the Life series about Paris lovers, he had spotted Françoise Bornet and her then boyfriend Jacques Carteaud near the school where they were studying theatre, and they agreed to pose.

Some 40 years later, Bornet surfaced and showed Doisneau the original print bearing his signature and stamp, which he had sent her just a few days after the shoot. The couple didn’t stay together; Carteaud became a wine producer. In 2005, Bornet sold her original print for €156,000 at auction.

But it turns out that there’e even more to the picture. Look further into it:

The man in the beret striding purposefully behind the couple was Jack Costello, an auctioneer from Dublin, who was on a pilgrimage to Rome when the photograph was taken. It was 1950, a holy year, and he had travelled from his home in Clontarf by motorbike with a neighbour to join in the religious commemorations in Rome – the first and only time he ever travelled abroad. Costello is thought to have been sightseeing alone in Paris when he wandered into Doisneau’s frame. He never lived to enjoy his fame, alas. It wasn’t until the early 1990s that one of his sons spotted his father in a large poster of Le Baiser in a shop window in Dublin.

There’s a novel in this, you know. (Memo to self: phone Colm Toibin.)