On the waterfront

Wells-next-the-Sea late on Friday afternoon. Beautifully still. Tide still out.

Quote of the Day

“Etiquette” used to be the second-most stolen book from the library after the Bible (which presumably is taken by people unfamiliar with the Ten Commandments).

- Louis Menand, in his New Yorker review of Jess McHugh’s Americanon.

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Handel | Gentle Morpheus | Alceste | Emma Kirkby

An aria I didn’t know — until last week. Better late than never.

Long Read of the Day

Climate optimism of the will

Noah Smith’s surprisingly passionate argument that climate fatalism is both misguided and disabling. His point is

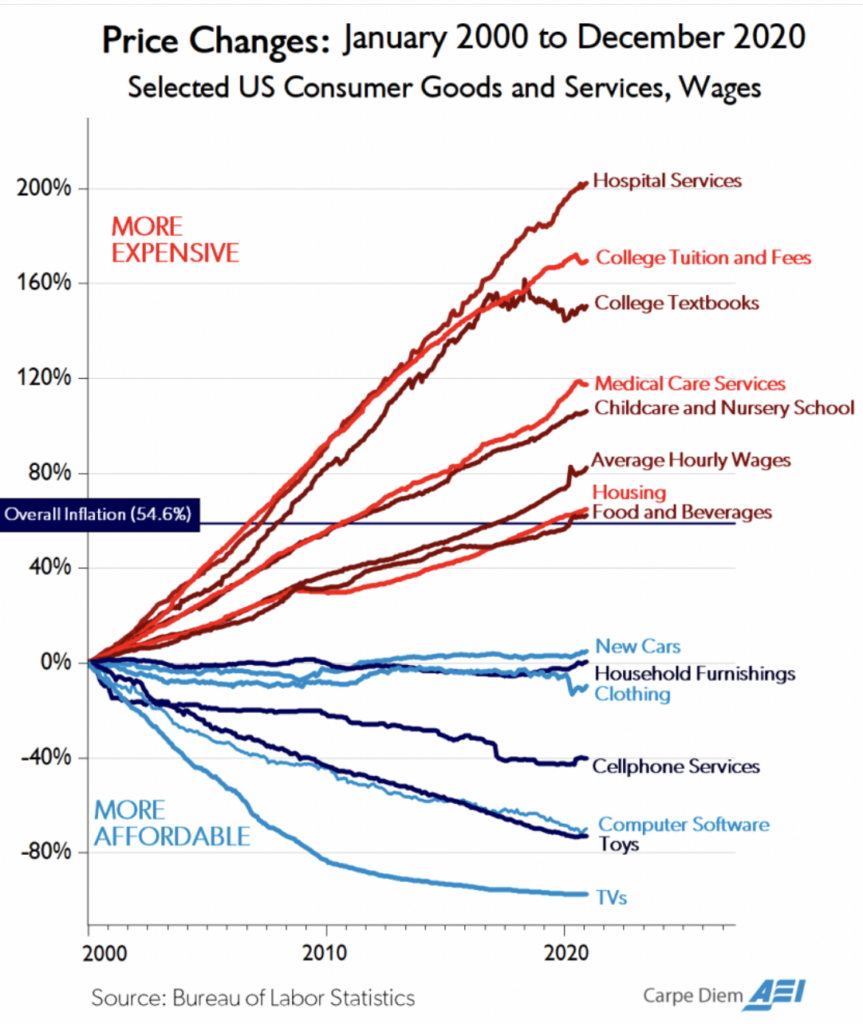

that we don’t have to depend on any one magical deus ex machina technology to come and save us. There is no single such technology. Instead, everywhere you look, scientists and engineers are inventing new technologies to maintain our industrial society while eliminating greenhouse emissions. And everywhere you look, companies are eager to both develop and purchase these technologies, promising to bring them down in cost the way solar and batteries have fallen in cost.

And a new report from the Institute for New Economic thinking suggests that this flurry of technological innovation has already changed the game in a fundamental way. In “Empirically grounded technology forecasts and the energy transition”, INET’s team notes that we’ve consistently underestimated progress in renewable technology. They argue that realistic forecasts mean that green energy will be so cheap that even businesses that don’t care about climate at all will now find it worth their while to ditch fossil fuels.

As a pessimist about climate change who also realises that pessimism is disabling, I found this piece refreshing. Hope you do too.

Whistleblowing requires courage, but don’t expect Facebook to change its ways

Yesterday’s Observer column:

The bigger question is whether whistleblowing does any good even when it is accomplished as skilfully as she has managed it to date. Does it lead to meaningful change?

Take Edward Snowden’s case. His revelations were genuinely sensational, revealing the astonishing scale and comprehensiveness of the NSA’s (and its allies’) electronic surveillance. It was clear that the democratic oversight of this surveillance in a range of western countries had been woefully inadequate in the post-9/11 years. Facebook chief executive officer Mark Zuckerberg

The revelations triggered inquiries in many of those countries, but what actually happened? In the US, very little. In the UK, after three separate inquiries, there was a new act of parliament – the Investigatory Powers Act 2016, which replaced inadequate oversight with slightly less inadequate oversight and gave the security services a set of useful new powers.

Will it be any different with the Haugen revelations? My hunch is no, because the political will to tackle Facebook’s astonishingly profitable abuse is still missing…

Do read the whole thing. _

Great news for Facebook: it’s no longer the most toxic social network!

Trump has a new social media operation. Marina Hyde celebrates its arrival in her inimitable style:

For now, Facebook is only convincingly troubled by “disinformation” if it’s about itself. We don’t know what will emerge next week, but we can be almost sure how the firm will react to it. The usual MO of Facebook’s chiefs has been to deny they even did the thing they’re being accused of, until the position becomes untenable. At that point, they concede they did whatever it was on a very limited scale, until that position becomes untenable. Next up is accepting the scale was more widespread than initially indicated, but with the caveat that the practice has now come to an end, until that position is the latest to become untenable.

Clear evidence that the practice never came to an end and, in fact, only became more widespread will come with aggressive reminders that it is not and never has been technically illegal. If and when whatever-it-is has been proved to be technically illegal after all, Facebook will accept the drop-in-their-ocean fine, with blanket immunity for all senior officers, and move back to step one in the cycle. We get rinsed; they repeat.

Such a wonderful columnist.

Amazon’s ambitions to build an air freight empire got a lift from the pandemic

From: Quartz:

Amazon went on a plane buying spree in the pandemic summer of 2020, fueling the fastest expansion yet of its air fleet. “They had plans for this, but the pandemic obviously pulled forward everyone’s demand for e-commerce and strained Amazon’s shipping capacity,” said John Blackledge, an analyst at the investment bank Cowen.

In 2020 alone, Cowen analysts estimate that Amazon invested $80 billion in logistics infrastructure—everything from warehouses to trucks to cargo planes—and they expect the company will wind up spending another $80 billion in 2021. That compares to the $56 billion Amazon spent on logistics infrastructure in the five years between Amazon Air’s launch in 2015 and the onset of the pandemic in late 2019, Cowen analysts estimate.

Amazon’s air freight investments aren’t just an urgent effort to move goods faster as the holiday shopping season approaches: Analysts who watch Amazon believe it will be one of the first steps toward competing directly with incumbent couriers like FedEx and UPS as a global delivery service.

My Commonplace booklet

Eh? (See here)

“Simulations reveal that ducklings swimming in a single-file formation behind the parent can achieve a wave-riding benefit whereby the wave drag turns positive. — from The Journal of Fluid Mechanics, no less.

Gives a new meaning to ‘getting your ducks in a row’!

This blog is also available as a daily newsletter. If you think this might suit you better why not sign up? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. And it’s free!