What’s surprising about JP Morgan Chase’s admission that it ‘lost’ $2billion in the trading of complex financial derivatives is not that it happened but what it demonstrates about how our democracies have been captured by a banking system which continues to thumb its nose at legislators. For Jamie Dimon, the chief executive of JPMorgan Chase who had to reveal the cock-up in a call to analysts, was — and no doubt remains — a fierce opponent of tighter regulation of the banking system, and especially of any rule that might constrain banks from unduly risky behaviour. “What Mr. Dimon did not say”, observed the New York Times,

is that the loss also occurred because of a continued lack, nearly four years after the crisis, of rules and regulators up to the task of protecting taxpayers and the economy from the excesses of too big to fail banks; and, yes, of protecting the banks from their executives’ and traders’ destructive risk-taking.

The fact that JPMorgan’s loss — which Mr. Dimon has warned could “easily get worse” — is not enough to topple the bank, is not the point. What matters is that JPMorgan, like the nation’s other big banks, is still engaged in activities that can provoke catastrophic losses. If policy makers do not strengthen reform, then luck is the only thing preventing another meltdown.

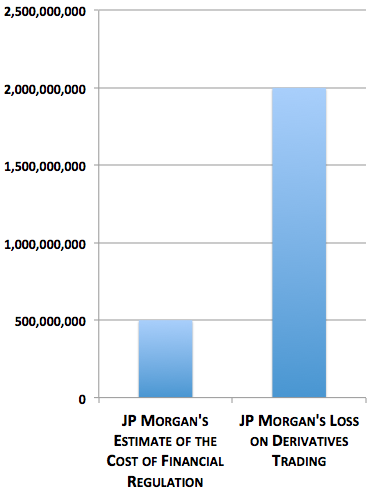

All of which brings to mind Mr Dimon’s ferocious opposition to the Dobb-Frank Act, which was the Congressional response to the banking catastrophe, compliance with which — he claimed — would cost his bank $400m-$600m annually. The Dobb-Frank Act was also the object of sustained ridicule by the Economist magazine in a long piece last February (which quoted Dimon’s estimate of the cost of compliance). The piece attacked what it portrayed as flaws in “the confused, bloated law passed in the aftermath of America’s financial crisis”, but failed to observe that one reason for the complexity of Dodd-Frank was the unconscionable complexity of the financial system that it was attempting to regulate.

The other thing that, strangely, escaped the notice of Economist is the need to make a cost-benefit assessment of initiatives like Dodd-Frank. Sure, the costs it imposes on banks are no doubt heavy; sure, it will give employment to lawyers and form-fillers. But what about the costs that the banking meltdown has inflicted on our societies (as some readers of the Economist pointed out in letters to the Editor the following week)?

But perhaps the most acute angle on the irony of JP Morgan Chase’s screw-up is provided by this chart by Derek Thompson of The Atlantic:

The NYT points out that the Dodd-Frank Act also calls for new rules on derivatives — including transparent trading and requirements for banks to back their trades with collateral and capital. If such rules were in place, JPMorgan’s trades could not have escaped notice by regulators and market participants. In the face of heavy lobbying, the derivatives’ rules have also been delayed or watered down. But guess what?

There are now several bills in the House, with bipartisan support, to weaken the Dodd-Frank law on derivatives. One of those would let the banks avoid Dodd-Frank regulation by conducting derivatives deals through foreign subsidiaries. The JPMorgan loss was incurred in its London office, which doesn’t lessen the effect here.

Finally — and needless to say — Mitt Romney has called for repealing the Dodd-Frank Act. Sometimes, one wonders if there is any intelligent life left on earth.