The best time of the day in Provencal villages is the early morning, when the locals are up and about and the holidaymakers haven’t woken up yet.

That “Apple Tax”

Horse sense from Jean-Louis Gassée

Following last week’s verdict against Samsung, the kommentariat have raised the specter of an egregious new Apple Tax, one that Apple will levy on other smartphone makers who will have no choice but to pass the burden on to you. The idea is this: Samsung’s loss means it will now have to compete against Apple with its dominant hand — a lower price tag — tied behind its back. This will allow Apple to exact higher prices for its iPhones (and iPads) and thus inflict even more pain and suffering on consumers.

There seems to be a moral aspect, here, as if Apple should be held to a higher standard. Last year, Apple and Nokia settled an IP “misunderstanding” that also resulted in a “Tax”…but it was Nokia that played the T-Man role: Apple paid Nokia more than $600M plus an estimated $11.50 per iPhone sold. Where were the handwringers who now accuse Apple of abusing the patent system when the Nokia settlement took place? Where was the outrage against the “evil”, if hapless, Finnish company? (Amusingly, observers speculate that Nokia has made more money from these IP arrangements than from selling its own Lumia smartphones.)

Pivotal moments

From Dave Winer.

And today Neil Armstrong died. And yes, I remember where I was the day he landed on the moon. I was at the Newport Folk Festival in Newport, Rhode Island. Thousands of us were watching the landing from a small portable TV on top of a VW minibus. I couldn’t really see what was happening, but I remember the moment, very emotional, a moment of pride and amazement at what we could do. It was one of those “pinch me” moments. I still feel the emotional charge now, 43 years later.

Latour on ecocatastrophe and “re-enacting science”

Great talk at Trinity College, Dublin last April. Worth making an “appointment to view”.

Ice

Harrying Harry

“What’s next?” asks Glen Newey on the LRB blog after the Sun publishes pics of Prince Harry in the nude.

The Prince of Wales in Photoshopped congress with a polo mare? Princess Anne on the can? This blogger is hardly one to shield the royals from the blastments of the public sphere. It’s not exactly what John Stuart Mill had in mind in Chapter 2 of On Liberty. There is the argument that the Sun is to liberty what cowpats are to fillet steak, an unavoidable byproduct, however unpalatable, of something there’s good reason to promote (vegetarians may substitute a different analogy). But, of course, you don’t just get the pat itself – you get its producer trying to pass it off as something wholesome. On the subject of plausible half-truths and their exposure, recall Geoffrey Robertson’s immortal observation that Rupert Murdoch is a great Australian in more or less the same sense that Attila was a great Hun.

Lovely blog post. Worth reading in full.

Apple’s Big Patent Win: implications

Interesting WSJ piece by Mike Isaac about Apple’s victory over Samsung.

If there’s one takeaway from Apple’s massive win over Samsung in the most-watched patent trial of the year, it’s this: If you copy our stuff, we’ll go after you.

That’s the message delivered alongside the verdict on Friday afternoon, in which the jury found Samsung guilty of infringing upon six out of the seven Apple patents in question. The result? More than $1 billion in damages awarded to Apple (or $1,049,343,540 if you want to get nitpicky about it), and of course, bragging rights in what has been Apple’s longstanding claim that Samsung devices were “slavishly copies” of Apple’s iPhone and iPad.

And now that Apple’s day in court has validated most of its patents and claims, the technology giant is armed to the teeth with enough ammo to go after any and every OEM out there.

The obvious implication is that Android OEMs need to be careful (as Charles Arthur points out). A less obvious one is that this might be good news for makers of Windows phones, on the grounds that they are less vulnerable to IP attacks from Apple than Android OEMs. Hmmm…

Ultimately, this patent verdict is bad news for everybody except Apple — as Dan Gillmor points out in his Guardian column. And it confirms the extent to which the patent system is broken.

Nailing Congressman Ryan

Lovely dissection of Paul Ryan by Leon Wieseltier.

Then there is the matter of Ryan’s intellectualism. His promoters have made much of it. “He’s a guy who, unlike 98 percent of members of Congress, can sit in a conference or around the dinner table with six or ten people from think tanks and magazines and more than hold his own in a discussion,” said William Kristol, thereby establishing the definition of the intellectual as a person who knows how to talk to William Kristol. A close look at Ryan’s writings, however, shows an intellectual style that is amateurish and parochial. His thought is just a package. The distinction between an analysis and a manifesto is lost on him. He gets his big ideas second-hand, from ideological feeders: when he cites John Locke, it is John Locke that he found in Michael Novak (who erroneously believes that strawberries appear in the philosopher’s account of the creation of property by the mixing of labor with nature). Irving Kristol and Charles Murray are Ryan’s other authorities; and of course Rand, who was a graphomaniacal demagogue with the answers to all of life’s questions. His picture of the New Deal and the Depression is taken from—where else?—Amity Shlaes. When Ryan cites Tocqueville, it is as “Alexis-Charles-Henri Clerel de Tocqueville,” and when he cites Sorel it is as “Georges Eugene Sorèl,” which is the Wikipedia usage (except for the misplaced accent, which is Ryan’s contribution). When he cites Sorel, he seems unaware that he is appealing to a thinker who admired Lenin and Mussolini and advocated the use of violence by striking unions. (Scott Walker has no greater enemy than Georges Sorel.) Similarly, Ryan cites an encomium to the United States by “Alexandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn” without any apparent awareness that three years later the Russian writer issued a virulent denunciation of America and its “decadence.”

A bargain?

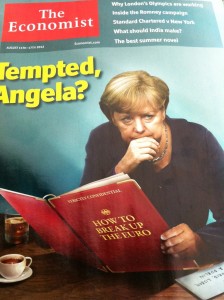

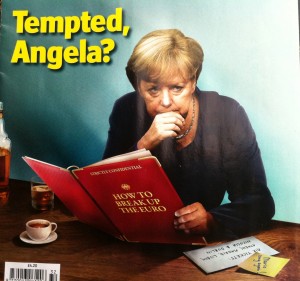

Cover Art: an exegesis

I don’t know who does the covers for the Economist but s/he is a genius.

Consider this one on the issue of August 11-17, 2012.

It shows the German Chancellor pondering a question that must be on every Eurocrat’s mind, but one that nobody dares to speak about: whether to ditch the Euro, and if so how to do it. I’m willing to bet that every Finance Ministry in Europe has a bulging secret file on the subject.

What’s fascinating about the picture is the amount of narrative detail it contains. Here it is close up.

Note the detail. First of all, the ‘strictly confidential’ Cabinet file (though it’s in a Whitehall-style red leather binder; I suspect the German Chancellery favours dark green leather.)

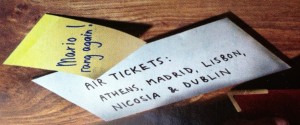

Next to her left arm is an envelope containing the airline tickets to the various capitals that need to be visited bearing the bad news. And the post-it note revealing the increasingly desperate calls from Mario Draghi, the Chairman of the European Central Bank.

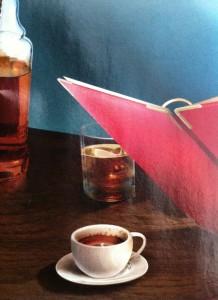

And then on the other side, the black coffee and whiskey needed to fortify her for the awful decision she will eventually have to make.

Not many magazine covers can stand this kind of exegesis. I hope that the Economist plans one day to have an exhibition of its best work. Some of us would pay good money for a signed copy of a cover like this.