A presidential study

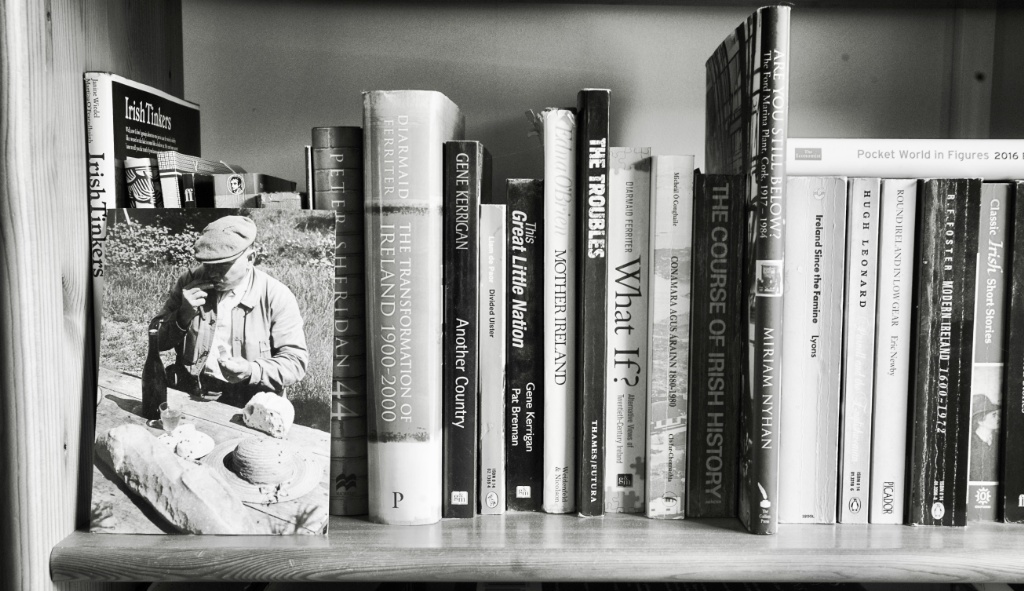

Michael D. Higgins, the current President of my native land (shown here entertaining Joe Biden last week) is a serious intellectual and author, and his study demonstrates this perfectly. Not for him the immaculately pristine, sterile desks of Macron & Co, but the untidy mess familiar to any working writer. Er, like me. (See below.)

Quote of the Day

”No I ask it for the knowledge of a lifetime.”

- J. A. Whistler, the Victorian painter, in answer to a barrister who, in his legal case against John Ruskin, had asked “For two days’ labour you ask two hundred guineas?”

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Rachmaninov | Variation 18 from “Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini” | Khatia Buniatishvili

Pure schmaltz, but lovely all the same.

Long Read of the Day

My Controversial Diatribe Against “Skeptics”

If you like diatribes — and I do — then you may enjoy this one by John Horgan, the famous science journalist.

Here’s a sample:

I hate preaching to the converted. If you were Buddhists, I’d bash Buddhism. But you’re skeptics, so I have to bash skepticism.

I’m a science journalist. I don’t celebrate science, I criticize it, because science needs critics more than cheerleaders. I point out gaps between scientific hype and reality. That keeps me busy, because, as you know, most peer-reviewed scientific claims are wrong.

I’m a skeptic, but with a small S, not capital S. I don’t belong to skeptical societies. I don’t hang out with people who self-identify as capital-S Skeptics. Or Atheists. Or Rationalists.

When people like this get together, they become tribal. They pat each other on the back and tell each other how smart they are compared to those outside the tribe. But belonging to a tribe can make you dumber.

Here’s an example involving two idols of Capital-S Skepticism: biologist Richard Dawkins and physicist Lawrence Krauss. In his book A Universe from Nothing, Krauss claims that physics is answering the old question, Why is there something rather than nothing?

Krauss’s book doesn’t fulfill its title’s promise, not even close, but Dawkins loved it. He writes in the book’s afterword: “If On the Origin of Species was biology’s deadliest blow to supernaturalism, we may come to see A Universe From Nothing as the equivalent from cosmology.”

Just to be clear: Dawkins is comparing Lawrence Krauss, a hack physicist, to Charles Darwin. Why would Dawkins say something so dumb? Because he hates religion so much that it impairs his scientific judgment. The author of The God Delusion succumbs to what you might call the science delusion…

Great stuff. And he’s right: righteous folks never like being taken apart, or indeed mocked. I learned this many years ago when I was lived in an ultra-liberal middle-class neighbourhood (which I christened ‘the Muesli Belt’). In an Observer column I took the mickey out of my neighbours for the way they suddenly became aerated about a sex-shop opening up in the vicinity. And, boy, were they cross! And pompous with it. The only exception was a nice architect who mildly opined that the only thing he objected to was that the shop in question didn’t take American Express.

Books, etc.

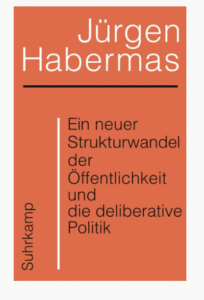

Jurgen Habermas has a new book out — A New Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. Sadly, it’s in German, a language I don’t speak. I guess there’s an English translation on the way.

Elon Musk hates journalists but journalists love Twitter. Where does that leave us?

Yesterday’s Observer column:

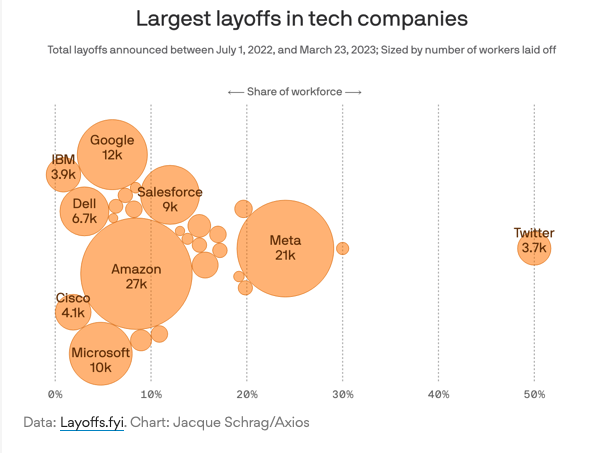

Last October, the richest manchild in human history fell into the trap he had dug for himself. Elon Musk was forced to purchase Twitter at an absurd price. He had no clear idea of what to do with his new acquisition, other than realising a fatuous idea about “free speech”. It was like watching a monkey acquire a delicate clock: the new owner started thrashing wildly about, slashing the headcount (from 8,000 to about 1,500) – in the process losing many of the people who knew how the machine worked – and generally having tantrums while tweeting incontinently from the smallest room in the company’s San Francisco headquarters.

All of this frenetic activity was watched – and avidly reported for weeks – by the world’s mainstream media, for reasons that would have puzzled a visiting Martian anthropologist. After all, in relation to the other social-media companies, Twitter looked like a minnow. Most people have never used it. So why all the fuss about its acquisition by a flake of Cadbury proportions?

The answer is that there is a select category of humans who are obsessive users of Twitter: politicians; people who work in advertising, PR and “communications”; and journalists…

Do read the whole thing.

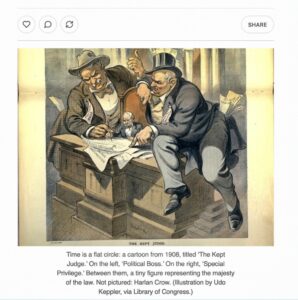

The continuing decay of the American republic

From “The Court Can’t Heal Itself”, a sobering essay by James Fallows on the, er, cosy relationship between Supreme Justice Clarence Thomas and a wacky billionaire, Harlan Crow.

My commonplace booklet

Not Too Late

An interesting initiative by Rebecca

NotT00Late is a project to invite newcomers to the climate movement, as well as provide climate facts and encouragement for people who are already engaged but weary. We believe that the truths about the science, the justice-centered solutions, the growing strength of the climate movement and its achievements can help. They can assuage the sorrow and despair, and they can help people see why it’s worth doing the work the climate crisis demands of us.

This Blog is also available as a daily email. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!