RIP.

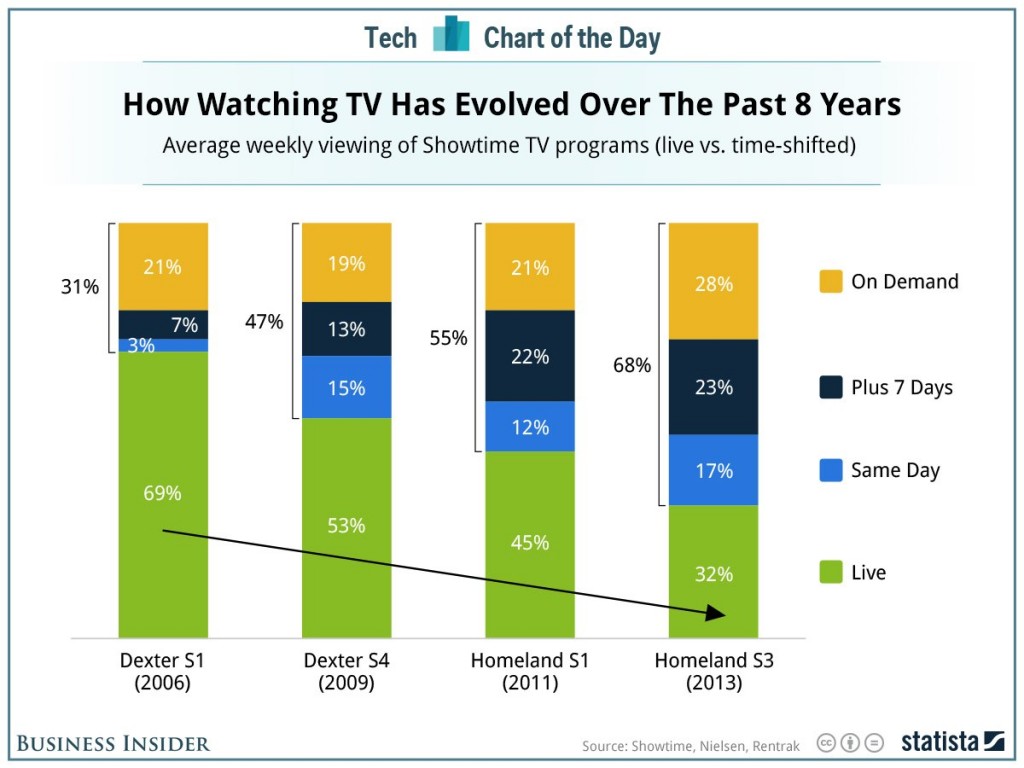

The slow death of water-cooler TV

Advancing hordes

This extraordinary snapshot showing German infantry advancing through crops in a Belgian field captures something of the shock of warfare that — for most people — came more or less out of the blue. I came on it (of course) while I was looking for something else. That’s the Web for you.

The Vase

In the wonderful Fondation van Gogh in Arles.

The lady with the hat

Google knowledge

Nice cartoon in the New Yorker. Wife is mopping up pools of water created by her husband, who is (incompetently) washing up: “Do you really know what you’re doing” she asks, “or do you Google-search know?”

Why Wikipedia matters

This morning’s Observer column.

Wikipedia is a typical product of the open internet, in that it started with a few simple principles and evolved a fascinating governance structure to deal with problems as they arose. It recognised early on that there would be legitimate disagreements about some subjects and that eventually corporations and other powerful entities would try to subvert or corrupt it.

As these challenges arose, Wikipedia’s editors and volunteers developed procedures, norms and rules for addressing them. These included software for detecting and remedying vandalism, for example, and processes such as the “three-revert” rule. This says that an editor should not undo someone else’s edits to a page more than three times in one day, after which disagreements are put to formal or informal mediation or a warning is placed on the page alerting readers that there is controversy about the topic. Some perennially disputed pages, for example the one on George W Bush, are locked down. And so on.

In trying to figure out how to run itself, Wikipedia has therefore been grappling with the problems that will increasingly bug us in the future. In a comprehensively networked world, opinions and information will be super-abundant, the authority of older, print-based quality control and verification systems will be eroded and information resources will be intrinsically malleable. In such a cacophonous world, how will we know what is reliable and true? How will we deal with disagreements and disputes about knowledge? How will we sort out digital wheat from digital chaff? Wikipedia may be imperfect (what isn’t?) but at the moment it’s the only model we have for addressing these problems.

Illegal spying below

Lovely! Good example of liberal chutzpah.

Oh what a complicated war

I’ve just finished Christopher Clark’s remarkable book about the origins of the First World War. It’s very well-written but it’s not an easy read because Clark’s mill grinds exceedingly fine and he has an astonishing capacity for archival research across a range of languages. So the reader winds up knowing far more than he bargained for about the detailed intricacies of foreign policy and what passed for strategic thinking in a whole range of European governments.

Given that, the sales of the book are nothing short of extraordinary. The Economist claims that it has sold over 300,000 copies, for example. What’s even more extraordinary is that it has sold 130,000 copies in Germany.

This has puzzled some commentators, but I think I know the reason for its popularity there. It is that, whereas the conventional wisdom about responsibility for the war has generally pointed the finger at Germany, Clark’s analysis is more nuanced. One way of interpreting his analysis is that the urge to war was the emergent property of a complex, interactive system, the actors in which were confused, riven by internal contradictions, and had poor information about the intentions and deliberations of all the other players in the game.

Here’s how he puts it in his conclusion:

“The outbreak of war in 1914 is not an Agatha Christie drama at the end of which we will discover the culprit standing over a corpse in the conservatory with a smoking pistol. There is no smoking gun in this story; or, rather, there is one in the hands of every major character. Viewed in this light, the outbreak of war was a tragedy, not a crime. Acknowledging this does not mean that we should minimise the belligerence and imperialist paranoia of the Austrian and German policy-makers that rightfully absorbed the attention of Fritz Fischer and his historiographical allies. But the Germans were not the only imperialists and not the only ones to succumb to paranoia. The crisis that brought war in 1914 was the fruit of a shared political culture. But it was also multipolar and genuinely interactive – that is what makes it the most complex event of modern times and that is why the debate over the origins of the First World War continues, one century after Gavrilo Princip fired those two fatal shots on Franz Joseph Street.”

How Hamas does rocketry

Interesting video by a journalist with more courage than sense.