The entrance to the Van Gogh Foundation in Arles.

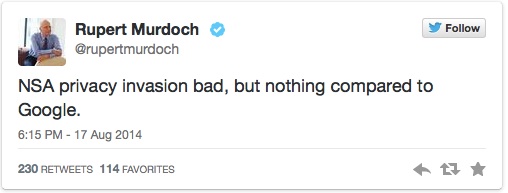

Pot calls kettle black

On balance…

What SIlicon Valley chooses not to know

This morning’s Observer column.

It is difficult to get a man to understand something,” wrote Upton Sinclair, the great American muckraking journalist, “when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” That was in 1935, so let us update it for our times: “It is impossible to get an executive of an internet company to understand anything if the value of his (or her) stock options depends on not understanding it.”

There are two things in particular that the various infant prodigies, charlatans, megalomaniacs, sociopaths and venture capitalists who run our great internet companies have a vested interest in not understanding…

Harley

Our out-of-control police forces

I hold no brief for Cliff Richard, but the behaviour of Thames Valley and Yorkshire Police forces in relation to him has been outrageous. Geoffrey Robertson QC has a terrific article about it in today’s Independent.

Last year, apparently, a complaint was made to police that the singer had indecently assaulted a youth in Sheffield a quarter of a century ago. The police had a duty to investigate, seek any corroborating evidence, and then – and only if they had reasonable grounds to suspect him of committing an offence – to give him the opportunity to refute those suspicions before a decision to charge is made.

But here, police subverted due process by waiting until Richard had left for vacation, and then orchestrating massive publicity for the raid on his house, before making any request for interview and before any question could arise of arresting or charging him.

Police initially denied “leaking” the raid, but South Yorkshire Police finally confirmed yesterday afternoon that they had been “working with a media outlet” – presumably the BBC – about the investigation. They also claimed “a number of people” had come forward with more information after seeing coverage of the operation – which leads one to suspect that this was the improper purpose behind leaking the operation in the first place. This alone calls for an independent inquiry.

The BBC and others were present when the five police cars arrived at Richard’s home, and helicopters were already clattering overhead. Police codes require that “searches must be conducted with due consideration for the property and privacy of the occupier and with no more disturbance than necessary” – here, the media were tipped off well ahead of time, and a smug officer read to the cameras a prepared press statement while the search was going on.

Among other things, if it’s true that the BBC was involved in this then the Corporation has serious questions to answer about its complicity in this. What would make it doubly ironic would be the fact that this is the same BBC that for decades provided cover and opportunities for the biggest sexual predator in recent history, Jimmy Saville.

So, first question: was the BBC complicit in this?

Second question: who was the magistrate who allowed this to proceed? “Why was a search warrant granted?” asks Robertson.

The law (the 1984 Police and Criminal Evidence Act) requires police to satisfy a justice of the peace not only that there are reasonable grounds for believing an offence has been committed (if so, why had he not already been arrested?), but that there is material on the premises both relevant and of substantial value (to prove an indecent assault 25 years ago?).

Moreover, the warrant should only be issued if it is “not practicable to communicate” with the owner of the premises – and it would be a very dumb police force indeed that could find no way of contacting Cliff Richard. The police Codes exude concern that powers of search “be used fairly, responsibly, with respect for occupiers of premises being searched” – this search was conducted without any fairness or respect at all, other than for the media who were given every opportunity to film the bags of “evidence” being taken away.

This whole thing is a scandal. But because the popular press — and maybe the BBC — were in on it, nothing will happen.

Later A statement from South Yorkshire police:

The facts are as follows:

The force was contacted some weeks ago by a BBC reporter who made it clear he knew of the existence of an investigation. It was clear he in a position to publish it.

The force was reluctant to cooperate but felt that to do otherwise would risk losing any potential evidence, so in the interests of the investigation it was agreed that the reporter would be notified of the date of the house search in return for delaying publication of any of the facts.

Contrary to media reports, this decision was not taken in order to maximise publicity, it was taken to preserve any potential evidence.

South Yorkshire Police considers it disappointing that the BBC was slow to acknowledge that the force was not the source of the leak.

A letter of complaint has been sent to the Director General of the BBC making it clear that the broadcasters appears to have contravened it’s editorial guidelines.

Increasing returns

In 1984, you could have bought a single share in Warren Buffett’s investment company, Berkshire Hathaway, for $1,300. Yesterday, you could have sold that share for $200,000. Sadly, in 1984 I didn’t have $1,300 to spare. And I’d never heard of Berkshire Hathaway.

Sigh.

Recycled news

Lovely column by Jack Shafer about why news headlines seem so familiar. Sample:

But the periodicity of the news has another cause, as press scholar Jack Lule discovered more than a decade ago in his book Daily News, Eternal Stories. Lule proposed that the news was less a pure journalistic creation than it was the modern expression of ancient myths.

Like many all-encompassing formulas, Lule’s reduction of news into myth suffers by attempting to explain too much. But after reading his book, you can’t help but notice how many front-page stories collapse into the seven master myths he assembles (which will sound familiar to anybody who has brushed up against Joseph Campbell’s The Hero With a Thousand Faces): the victim, a casualty of randomness or a villain; the scapegoat, who is punished for straying outside the social order; the hero, who smites evil; the good mother, who “offers maternal comfort and protection”; the trickster, the rogue who disturbs the social order; the other world, typically foreign countries; and the flood, or any other disaster.

Lovely stuff. Worth reading in full.

Quote of the Day

“Nostalgia is like a grammar lesson: you find the present tense, and the past perfect…”

Andrew McAfee

Or this?

We’ve lost a genius. May he rest in peace.