Wednesday 24 June, 2025

La creme de la café creme

Breakfast time in Provence.

Quote of the Day

“It’s easier being in each other’s presence, or in each other’s absence, than in the constant presence of each other’s absence.”

- Gianpiero Petriglieri, commenting on the abysmal experience of Zoom conversations.

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Bach | Cello Suite No. 4 (Allemande) | Charlie Zandieh

Long Read of the Day

The Editorial Battles That Made The New Yorker

If you like the New Yorker (and I do), you’ll enjoy this essay by Jill Lepore.

Sample:

It was

[William]Shawn, though, who proposed printing the entirety of John Hersey’s account of Hiroshima after the bomb in a single issue of the magazine, one of the best things The New Yorker ever did, aside from publishing the entirety of Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring,” in 1962. When Shawn first read Carson’s piece, he called to tell her that it might change the course of history. Carson hung up the phone, collapsed, and wept.Ross ran a humor magazine; Shawn ran a literary magazine that elevated reporting. In the years of American prosperity that followed the Second World War, the cachet of The New Yorker meant that it was flooded with advertisers. Shawn, needing to fill a swelling magazine’s pages, ran it like a book club, publishing some astonishingly important journalism, from Truman Capote’s “In Cold Blood” to Richard Rovere’s letters from Washington. But he also, especially as time wore on, ran no small number of staggeringly long and often mind-numbingly boring articles about little of consequence, or what Tina Brown took to calling the fifty-thousand-word piece about zinc—articles that, by the end of Shawn’s tenure, were no longer wending through pages of towering ads, avenues through a city of skyscrapers…

It’s a lovely piece, the product of long days slogging through the magazine’s archives in the New York Public Library.

I like the way she ended it.

As for the Punctuation Farm, it turns out that they’ve got livestock there, in the fields beyond the greenhouses where the periods, set in shallow pans, sprout into commas. “Readers are like cows—they just want to keep chewing what you feed them,” Bennet used to say. But writers are like sheep, woolly and steadfast and bleating. And the best editor, high in the hills, is like a shepherd, warding off the wolves, moving the flock to better pasture, rescuing lost lambs.

Personally, I’ve always liked being edited, and indeed one of the really nice things about writing for the Observer for so many years is that I’ve been edited by smart, careful and unsung sub-editors who have saved me from my naiveté, foolishness or carelessness more times than I dare to remember.

My commonplace booklet

Dave Winer on Bill Atkinson

Devoted readers will recall that my most recent Observer column was a tribute to Bill Atkinson, one of the software wizards of his era. But then I read this tribute by Dave Winer and I realised that I had only scraped the surface: I hadn’t covered Quickdraw. Dave, however, understood its significance and covered it beautifully.

I was explaining to a friend why he was so important. Most people who know of him know about MacPaint and Hypercard, both were fantastic contributions to the evolution of personal computers. But underneath all that he created a layer of the Macintosh OS called QuickDraw, which was a core innovation of the Mac, its graphic system. Every piece of software that ran on the Macintosh ran on top of QuickDraw.

Here’s what QuickDraw is. Software could do things at the pixel level, a dot so small it’s barely visible to the eye. What you’re seeing on the screen is made up of collections of those dots, forming lines, boxes, ovals and text, and later page layouts, beautiful photography, and the text you’re reading right now. The software that does all that, on the earliest Macs, is called QuickDraw. (Later a successor called QuickTime made the dots move and added sound, and now we have streaming.)

That’s the thing. You could tell from the API that the designers really understood the tech. It wasn’t the first time this had been done. And either Atkinson did it himself, working on it for years, or he “stole from the best” — probably a lot of both. The prior art came from Xerox in Palo Alto, and the experience came from being a hard-working dedicated hacker who didn’t give up until it was done. That’s like saying if he were a basketball hero, he was like Bill Russell or Steph Curry. We don’t talk about our accomplishments that much in tech, on a personal level, we have an idea that Steve Jobs made the Mac, but it was really created by developers, designers, graphic artists, writers and application developers. Like Bill Atkinson.#

I spent many years building on his work, and many more years wishing I still was. He made a contribution, and that’s, imho, pretty much the best you can say for any person’s life.

Yep. Lovely piece.

Linkblog

Something a reader noticed, while drinking from the Internet firehose.

- Cats’ acrobatic skills Link

Feedback

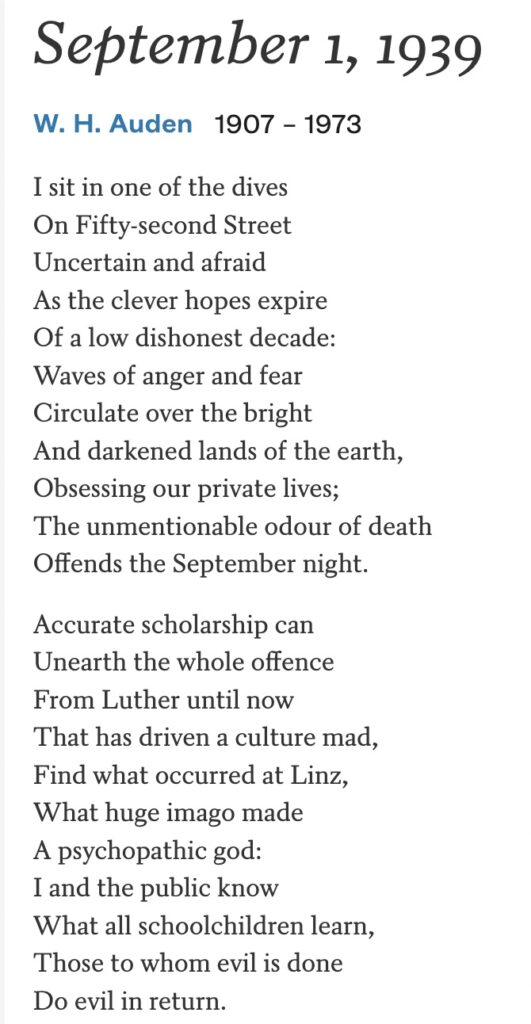

My TL;DR the other day saying that nobody ever learned to ride a bike by reading a manual prompted Andrew Curry (Whom God Preserve) to send me a link to Mark Twain’s essay, “Taming the Bicycle”. So I read it, and was then unable to do any work for several hours. If you read the opening, you can perhaps see why.

I thought the matter over, and concluded I could do it. So I went down and bought a barrel of Pond’s Extract and a bicycle. The Expert came home with me to instruct me. We chose the back yard, for the sake of privacy, and went to work.

Mine was not a full-grown bicycle, but only a colt—a fifty-inch, with the pedals shortened up to forty-eight—and skittish, like any other colt. The Expert explained the thing’s points briefly, then he got on its back and rode around a little, to show me how easy it was to do. He said that the dismounting was perhaps the hardest thing to learn, and so we would leave that to the last. But he was in error there. He found, to his surprise and joy, that all that he needed to do was to get me on to the machine and stand out of the way; I could get off, myself. Although I was wholly inexperienced, I dismounted in the best time on record. He was on that side, shoving up the machine; we all came down with a crash, he at the bottom, I next, and the machine on top.

We examined the machine, but it was not in the least injured. This was hardly believable. Yet the Expert assured me that it was true; in fact, the examination proved it. I was partly to realize, then, how admirably these things are constructed. We applied some Pond’s Extract, and resumed. The Expert got on the other side to shove up this time, but I dismounted on that side; so the result was as before.

The machine was not hurt. We oiled ourselves up again, and resumed. This time the Expert took up a sheltered position behind, but somehow or other we landed on him again.

He was full of surprised admiration; said it was abnormal. She was all right, not a scratch on her, not a timber started anywhere. I said it was wonderful, while we were greasing up, but he said that when I came to know these steel spider-webs I would realize that nothing but dynamite could cripple them. Then he limped out to position, and we resumed once more. This time the Expert took up the position of short-stop, and got a man to shove up behind. We got up a handsome speed, and presently traversed a brick, and I went out over the top of the tiller and landed, head down, on the instructor’s back, and saw the machine fluttering in the air between me and the sun. It was well it came down on us, for that broke the fall, and it was not injured.

Five days later I got out and was carried down to the hospital, and found the Expert doing pretty fairly. In a few more days I was quite sound. I attribute this to my prudence in always dismounting on something soft. Some recommend a feather bed, but I think an Expert is better…

I rest what might jokingly be called my case. Do read on.

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 5am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!