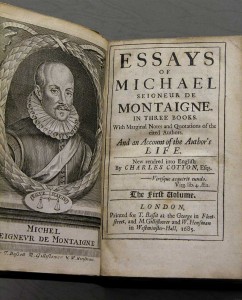

While making breakfast this morning I listened to the latest episode of Nigel Warburton’s and David Edmond’s wonderful Philosophy Bites podcast — a discussion of Montaigne with Sarah Bakewell, whose lovely book on the essayist I have read and enjoyed. Like most all of the Philosophy Bites podcasts, this one was thought-provoking and accessible (and I heartily recommend it), but the one thing I missed was any discussion of the similarity between Montaigne’s essays and the writing of good bloggers.

This comparison is not an original idea btw — I got it originally from Andrew Sullivan when I was working on my most recent book. But, as is the case with the Web, Andrew probably got it from Rob Goodman’s beautiful essay on the “Tyranny of Timeliness”, which says, in part:

As these digressions through literature, science, history, anecdote, and memory pile up, we sense that we are dealing not with a narrative, but with a network: no fact is an island; every point is linked to every other point in Montaigne’s mind by an endless array of invisible threads.

Of course, that’s how we all think. But it is not how we all write. Montaigne was unique in finding a written expression for the way conversations evolve organically, the way thought has a shadowy logic of its own; it’s why his essays are such a different animal from the essays we’re assigned in school, so different that they shouldn’t even bear the same name, and why we often feel more at home in them. He did it by being studiedly haphazard. And his achievement matches that of his contemporary, Shakespeare, who took years of experimentation to make his soliloquies sound less like declaimed speeches and more like overheard thought.

A Montaigne essay, like a Shakespeare soliloquy, gives us the impression that we are in the presence not of a disembodied, opinion-spouting voice, but of a real person. Long after those essays lost their relevance, long after the second-hand reports from the Americas and meditations on 16th-century French politics ceased to be news, they have maintained their appeal because they are a personality embodied. And the foremost trait of that personality is freedom: freedom to take up and turn over absolutely any subject in human experience, on any prompting or none; to follow any tangent simply because it catches his eye; to begin and end a continent apart, or simply to trail off; to know for the simple sake of knowing.

In Montaigne’s day, that freedom was the privilege of an aristocrat. Today, unless we trade it away for a mess of relevance, it’s the birthright of anyone with a high school education and an Internet connection.

My colleague Martin Weller also picked up on the Sullivan post and compiled this thoughtful list on what Montaigne means to him.

For me Montaigne shows the way for good bloggers through the following practices:

Honesty – you really can’t blog if you’ve got a hidden agenda. People have too much choice and so what you are after is some form of connection and this comes from people having good ideas, but also from connecting to them as an individual. Openness – as Sullivan points out in the quote above, one of the endearing qualities of Montaigne was his willingness to think out in the open. This is what bloggers do well, they put forward ideas, take criticism and comments, and develop those ideas partly in conjunction with their readers. They don’t work quietly for three years and then release a finished masterpiece (this is a good way of working for some writing, maybe novels, but not for blogs). Relaxed style – Montaigne really developed that chatty, informal style which is a lot harder than he makes it look. This is definitely the style that works best in blogs, because, to reiterate the point, part of what makes a good blog is a connection to the author. An element of the personal – Montaigne’s essays are famously rambling and rarely connected to the title. This approach doesn’t always work in blogs, which tend to be shorter posts focused on a particular point, but what does carry over is the way he brought in personal elements to back up and reinforce wider points, which a good blogger does without making it a boring shopping list. Reflective and questioning – good bloggers (and when I say a good blogger, I probably mean ‘bloggers I like reading’) seem to me to adopt Montaigne’s reflective approach, questioning themselves, and others. One of the delights of blogging is that it has no commercial masters to please and so bloggers tend to dig around a story, analyse it in detail and question every aspect of it (unlike many journalists who accept the PR from a company to fill space). Playfulness – I like bloggers who toy with ideas, mess around with media and inject some playfulness into their posts. Blogs liberate us from the considerations of many formal publications and I like people who embrace this. Owning a vineyard – oh, okay that one doesn’t apply.

In a much earlier post, Andrew Sullivan had a nice meditation on the political significance of blogging (something that would have been entirely alien to Montaigne, I suppose, but which is relevant to any consideration of how blogging affects the public sphere).

Michael Oakeshott’s conservatism owes a huge amount to Montaigne (and Augustine), which is why one of Oakeshott’s central metaphors is exactly conversation. He believed that such a metaphor captures the dramatic, undetermined, spontaneous and organic association of people in free societies. And such an open-ended conversation is, of course, the exact opposite of fundamentalism, which, in its extreme forms, demands no interaction, merely submission to a sacred, pre-ordained text. That’s why blogging is a little retrovirus called freedom, unleashed into the wider world of media to replicate endlessly. And why the blogosphere’s very existence and potential power is one of freedom’s most potent allies in our generation’s war against fundamentalism. Churchill once spoke of sending the English language into battle. He saw it as a great weapon against tyranny. It still is – in print, but just as powerfully, in pixels.

The point of all this is not to reinforce the trope about there being nothing new under the sun, but to counter the hubristic claims about everything digital being new. Of course the technology enables things that were inconceivable up to now, but it also facilitates and sometimes turbo-charges things that have been done for millennia. Like writing and thinking. And conversation.

LATER: Just realised that Sarah Bakewell has written a lovely blog post about all of this. It concludes thus:

These days, the Montaignean willingness to follow thoughts where they lead, and to look for communication and reflections between people, emerges in Anglophone writers from Joan Didion to Jonathan Franzen, from Annie Dillard to David Sedaris. And it flourishes most of all online, where writers reflect on their experience with more brio and experimentalism than ever before.

Bloggers might be surprised to hear that they are keeping alive a tradition created more than four centuries ago. Montaigne, in turn, might not have expected to be remembered so long, least of all in the English language—yet he always believed that such understanding between remote eras and cultures was possible. “Each man bears the entire form of the human condition,” he said. We are united in the very fact of our diversity, and “this great world is the mirror in which we must look at ourselves to recognize ourselves from the proper angle.” His book is such a world, and when we look into it there is no end to the strangeness and familiarity we might see.

Sigh. Maybe the heading for this post ought to have been “Thinking aloud”.