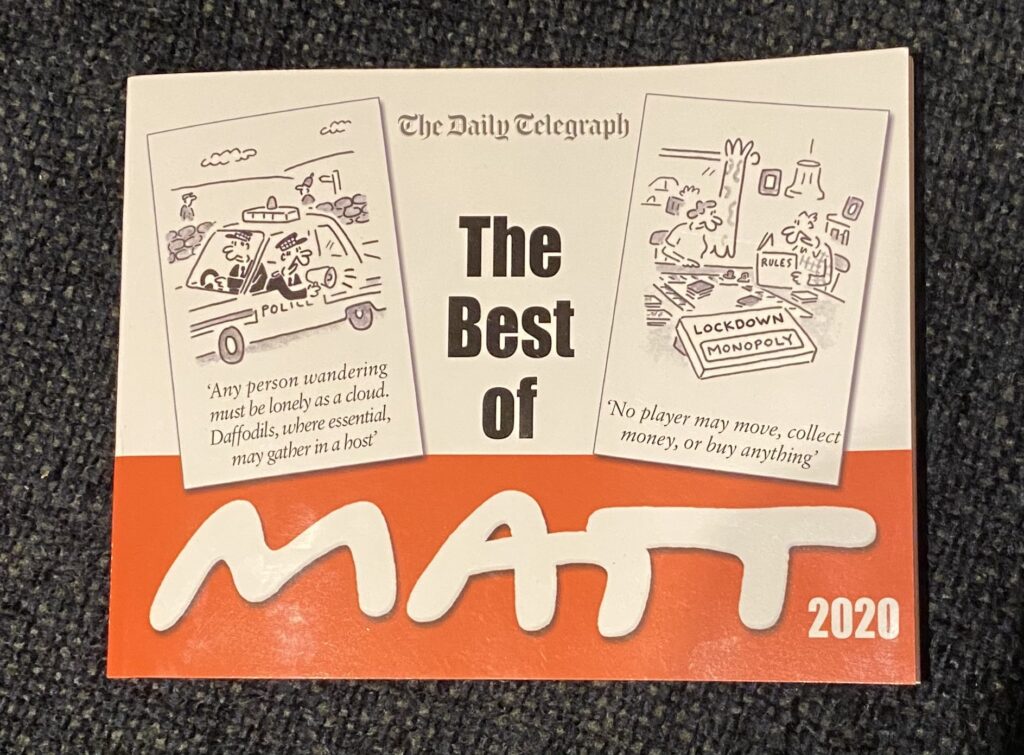

The genius who is Matt

Matt, the Daily Torygraph‘s cartoonist, is a genius. Which — my lovely daughter thought — is why his annual collection would be a great Christmas present for her Dad.

She was right. Here’s just one reason:

Quote of the Day

”The privately educated Englishman – and Englishwoman, if you will allow me – is the greatest dissembler on Earth. Was, is now and ever shall be for as long as our disgraceful school system remains intact. Nobody will charm you so glibly, disguise his feelings from you better, cover his tracks more skilfully or find it harder to confess to you that he’s been a damned fool.”

- George Smiley in John le Carré’s The Secret Pilgrim.

Remind you of anyone?

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Sharon Shannon | Blackbird

Long Read of the Day

John Rawls: can liberalism’s great philosopher come to the west’s rescue again?

Good question, thoughtfully discussed by Julian Coman in this Guardian Long Read:

He begins with the arguments that broke out in the New York Times on how the paper should cover Trump after his election as President. Confronted with a leader who delighted in flouting democratic norms and attacking minorities, was it the duty of this bastion of American liberalism to remain above the fray or should it play a partisan role in defence of the values under attack?

As journalists and staff argued online, a prominent columnist “uploaded a PDF of John Rawls’s treatise on public reason, in an attempt to elevate the discussion”. Rawls, who died in 2002, remains the most celebrated philosopher of the basic principles of Anglo-American liberalism. These were laid out in his seminal text, A Theory of Justice, published in 1971. The columnist, Elizabeth Bruenig, suggested to colleagues: “What we’re having is really a philosophical conversation and it concerns the unfinished business of liberalism. I think all human beings are born philosophers, that is, that we all have an innate desire to understand what our world means and what we owe to one another and how to live good lives.” One respondent wrote back witheringly: “Philosophy schmosiphy. We’re at a barricades moment in our history. You decide: which side are you on?”

In an age of polarisation, the exchange encapsulated a central question for the liberal left in America and beyond. Jagged faultlines have disfigured the public square during a period in which issues of race, gender, class and nationhood have divided societies. So was Bruenig right? To rebuild trust and a sense of common purpose, can we learn something by revisiting the most influential postwar philosopher in the English-speaking world?

Worth reading in full.

Reasons to be cheerful?

The economist Tyler Cowen is temperamentally an optimist; his glass is always three-quarters full. In his Bloomberg column 2020 “gets an asterisk for Covid”, but he thinks the year also saw great scientific progress. For example:

- The astonishingly rapid creation of several kinds of Covid-19 vaccines

- A “very promising” vaccine candidate against malaria, perhaps the greatest killer in human history

- New CRISPR techniques that appear to be on the verge of vanquishing sickle-cell anemia

- GPT-3 (AI) technology that composes remarkably human-like prose

- DeepMind’s machine learning system that seems to have cracked the problem of protein folding

- Driverless vehicles appeared to be stalled, but Walmart will be using them on some truck deliveries in 2021

- SpaceX achieved virtually every launch and rocket goal it had announced for the year.

- Toyota and other companies have announced major progress on batteries for electric vehicles, with related products are expected to arrive in 2021

- Lots of progress in affordable solar power

- China has developed a new and promising fusion reactor

- Many more Zoom meetings will be held, and many business trips will never return.

You get the picture. Professor Cowen is an upbeat kind of guy. But he’s also pretty perceptive about what’s going on.

Talking Politics @5

Talking Politics, the podcast founded and hosted by my friend and colleague David Runciman, has been going for five years. I’ve been a fan of it from the beginning, and occasionally ‘appeared’ on it (if that’s an accurate of describing participation in an audio recording). By any standards — and especially those of academic ‘engagement’ and outreach — the podcast has been a knockout success.

How do I know that? Well, ponder some of the statistics:

- Total downloads over the five years: 19.6m (20.57m if we include the History of Ideas strand)

- Total downloads in 2020: over 8.1m

- Weekly listens in 2020: 155,000 per week

- Countries reached in 2020: 197

This week’s edition was #295 and was devoted to some reflections on the five tumultuous years by David, Helen Thompson and Catherine Carr, the producer of the show. It’s well worth a listen. After hearing it I fell to pondering why TP has been so successful. Here are the notes I made…

-

Timing and luck. David made the point well — five years ago turned out to be a perfect moment to launch a show like TP because 2015 was a moment when democratic politics suddenly began to be interesting again. My own take on it is that the academic study of politics was just entering a phase which had the hallmarks of Thomas Kuhn’s description of the intellectual crises which scientific disciplines periodically go through as a field’s theoretical paradigm encounters increasing scepticism among researchers and a rival theoretical framework begins to emerge. A key feature of these crises, Kuhn observed, was incommensurability — the absence of a neutral language in which the merits of the old paradigm and its emerging rival could be objectively assessed. (Think Newtonian dynamics with its billiard balls vs quantum physics with its neutrinos, quarks and Higg’s boson.) So there’s initially no way of knowing which one ‘should’ win. The difference between the exact sciences and the social sciences is that, in the former, the experimental and observational facts are obtainable and so eventually obsolete paradigms die a natural death. That’s not the case in the social sciences (or indeed the humanities), which is why pathological paradigms (like rational expectations in economics) live on long past their sell-by dates. My hunch is that the theoretical paradigms which had governed what is laughingly called ‘political science’ lost credibility after the 2008 banking crisis and its aftermath, and TP thrived in the resulting vacuum of ideas.

-

Given that, the fact that TP was often ‘wrong’ –in its predictions and analyses but cheerful in its acceptance of that — was a feature not a bug. When you’re in a crisis of incommensurability, that’s the only way to act rationally. And, critically, it’s what conventional political analysis cannot do: it has to purport to possess a coherent narrative for what’s going on because those involved believe that their credibility depends on it. This is perhaps a measure of intellectual insecurity, and one of the defining characteristics of TP is that the main contributors and hosts don’t suffer from that and were therefore able to live with radical uncertainty in a way that members of the political commentariat could not!

-

Another thing that marked out TP from the burgeoning ruck of ‘politics’ podcasts was that it was forever escaping from “the sociology of the last five minutes”. No matter how urgent the question of the day, there was always Helen Thompson excavating the long history and political economy of how we got here, or Gary Gerstle or Adam Tooze doing the same, or Ken Armstrong explaining the incomprehensible complexities of regulatory divergence and related arcana. And so on.

-

In that sense, the podcast has been a showcase for the advantages of sheer erudition. There’s no substitute for it — as the discussion of the Corn Laws that was highlighted in this week’s edition demonstrated perfectly. And one of the great advantages TP had was that of being located in a major research university. It wouldn’t have been able to tap into this huge pool of collective IQ, however, had David Runciman and Helen Thompson not been recognised by their peers as formidable thinkers in their own right. Being invited to appear on TP was recognised by many distinguished thinkers as a real compliment.

-

Finally, TP was a great exploiter of the fact that podcasting has a wider intellectual bandwidth than other media — especially broadcast media which even on a good day have the bandwidth of smoke signals. When my son Pete (also a podcast producer) was making his ‘MPs’ Expenses’ series for the Telegraph, I remember thinking that if journalism is the first draft of history, then podcasting looks very much like the second draft. And Talking Politics is v2.1.

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if your decide that your inbox is full enough already!