Quote of the Day

”Worth seeing, but not worth going to see.”

- Samuel Johnson on the Giant’s Causeway in Co. Antrim.

(I respectfully disagree with the great Doctor in this case.)

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Jimmy Yancey | How Long Blues

Beautiful, just beautiful. And so simple.

Long Read of the Day

False Positivism versus Real Life

Thoughtful essay by Peter Polack on the implications of retreating into data-driven arguments as a way of navigating round ideologically-fuelled disagreements. An appeal to the objectivity of models can seem like an escape from subjective politics.

This idea has its roots in a longstanding desire to streamline political thought through an appeal to technical principles. It can be traced back at least to Auguste Comte’s 19th century positivism and his idea of developing a “social physics” that could account for social behavior with a set of fixed, universal laws. Later in the 19th century the term was taken up by statisticians, covering their racist criminological and sociological theories with a veneer of data. Now the premise of social physics lives on in everything from MIT professor Alex Pentland’s work on modeling human crowd behavior to the dreams of technocrats like Mark Zuckerberg, whose quest for “a fundamental mathematical law underlying human social relationships” is in conspicuous alignment with Facebook’s pursuit and implementation of a “social graph.”

But a “social physics” approach that broadens the horizon of computational modeling can seem appealing to more than just tech-company zealots. In more disinterested hands, a compelling political case can be made that it is the only viable way forward in a world out of control, marked by demagoguery and mistrust. As the hopes for modeling gain momentum, it will become increasingly important to articulate clearly its shortcomings, inconsistencies, and dangers.

Which is what this perceptive piece tries to do.

Why doesn’t whistleblowing lead to more real change?

Re-reading this piece by Os Keys in Wired made me wonder whether the astute campaign currently being run by Francis Haugen is likely to be any more effective at inducing real change than earlier whistleblowers.

“In this environment, whistleblowing can’t save us, because the issue isn’t an absence of information but an absence of will. And what builds will, and shifts norms, doesn’t look like a single, isolated figure speaking truth, but mass movements of people setting new standards and making clear there are costs to regulators and companies for not attending to them.”

Yep. Take the case of Edward Snowden. His revelations were genuinely sensational, revealing the astonishing scale and comprehensiveness of the NSA’s (and its allies’) electronic surveillance. It was clear that the democratic oversight of this surveillance in a range of Western countries had woefully inadequate in the post-9/11 years.

The revelations triggered inquiries in many of those countries. But what actually happened? In the US, very little. In the UK, after three separate inquiries, there was a new Act of Parliament — the Investigatory Powers Act 2016, which replaced inadequate oversight with slightly less inadequate oversight and gave the security services a raft of useful new powers.

Will it be any different with the Haugen revelations? Regretfully, my hunch is no because the political will to tackle Facebook’s astonishingly profitable abusiveness is still missing. Ms Haugen’s ‘testimony tour’ (she comes to Parliament here soon) will make for great copy and legislative grandstanding. But her revelations will “have zero impact on regulation. No new laws, no new regulations, no new challenges worth a damn” says Os Keys. The idea that when the truth gets out, good things happen — that regulators and corporate executives and legislators are ultimately just dependent on the right information to ensure justice is done — is a myth. Which is why the only regimes capable of taming companies like Facebook are autocracies. And we’re not there — yet.

Surprise: the Big Bang isn’t the beginning of the universe anymore

Damn! Is nothing sacred? We (well, cosmologists) used to think the Big Bang meant the universe began from a singularity. Nearly 100 years later, we’re not so sure. This long piece by Ethan Siegel, a theoretical astrophysicist, says that the Big Bang theory teaches us that our expanding, cooling universe used to be younger, denser, and hotter in the past. But apparently extrapolating all the way back to that cosmic ‘singularity’ leads to predictions that disagree with what we observe. Instead, “cosmic inflation preceded and set up the Big Bang, changing our cosmic origin story forever”.

This should probably be put in the “important if true but not directly relevant to the climate crisis” drawer. Fun to see how cosmologists think, though.

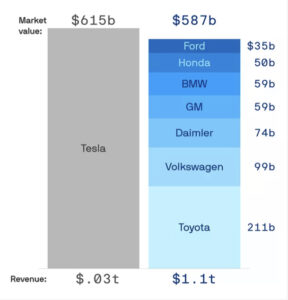

Chart of the Day

The moral: the stock market is a parallel universe to the one we inhabit.

My Commonplace booklet

Eh? (See here)

From Axios:

Companies that have returned more than 10,000% over 30 years — “superstocks,” as christened by fund manager William Bernstein of Efficient Frontier Advisors — all tend to crash at least once along the way.

Buying Apple stock 30 years ago would have been a fantastic investment, for instance: A $100 investment in October 1991 would be worth some $40,000 today.

But it was a bumpy ride: The same $100 would have been worth just $26.75 at the end of 1997.

This blog is also available as a daily newsletter. If you think this might suit you better why not sign up? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. And it’s free!