The view from… nowhere

I was brooding on something that the French painter Paul Delaroche is reputed to have said after seeing one of the first daguerreotypes in the late 1830s or early 1840s: “From today painting is dead”. Given the astonishing computational power that my iPhone now brings to bear on every image snapped by its camera, I was playing with the idea of an analogous slogan — “After computation, photography is dead!” And then, just for fun, I told Google’s LLM Gemini to create “a photo-realistic image of a young man, dressed in a business suit, climbing up the outside of the Eiffel Tower”, and a few seconds later this was the result.

Quote of the Day

”George Washington did not enjoy public speaking. Because of his dentures, made of a combination of elephant tusks, horse and cow teeth, and teeth pulled from the mouths of people he held as slaves, he found speaking for any length of time painful.”

- Historian Jill Lepore, writing in the New Yorker

Hmmm… not half as painful as what the slaves who made that involuntary sacrifice experienced.

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Elgar | Enigma Variations | Simon Rattle & the Berliner Phil

Still stops me in my tracks.

Long Read of the Day

Are We Doomed?

This is the cheery headline on a masterly LRB review-essay by David Runciman of a trio of books on the forthcoming global population collapse. I’ve read some of this stuff, and it makes one’s head spin sometimes, but this is the best summing-up of it I’ve come on.

Here’s a sample:

People are living longer than they used to. They are also having fewer children. The evidence of what this combination can do to a society is growing around the world, but some of the most striking stories come from Japan. For decades the Japanese health ministry has released an annual tally of citizens aged one hundred or over. This year the number of centenarians reached very nearly a hundred thousand. When the survey started in 1963, there were just 153. In 1981 there were a thousand; in 1998 ten thousand. Japan now produces more nappies for incontinent adults than for infants. There is a burgeoning industry for the cleaning and fumigating of apartments in which elderly Japanese citizens have died and been left undiscovered for weeks, months or years. Older people have far fewer younger people to take care of them or even to notice their non-existence. That neglect is a brute function of some simple maths. In 1950, Japan had a Total Fertility Rate (TFR) of 4, which represents the average number of children a woman might expect to have in her lifetime. Continued over five generations, that would mean a ratio of 256 great-great-grandchildren to every sixteen great-great-grandparents – in other words, each hundred-year-old might have sixteen direct descendants competing to look after them. Today Japan’s TFR is approaching 1: one child per woman (or one per couple, half a child each). That pattern continued over five generations means that each solitary infant has as many as sixteen great-great-grandparents vying for his or her attention. Within a century the pyramid of human obligation has been turned on its head.

There are two different ways to describe a family tree. You can start with an individual and trace their ancestry through parents and grandparents and beyond to produce a picture of the variety of human beings it takes to make up any one of us. That’s genealogy. The other version is to pick someone from an earlier generation – king or commoner – and count their direct descendants. That’s heredity. But the choice between the two approaches – one spreading out backwards and one spreading out forwards – is only possible because earlier generations tended to have multiple offspring. Once that ceases to be true, family trees start to look the same from both directions. That has never happened before and it is hard to know what it will mean. But it is going to feel oppressive…

Read on. It’s both gripping and sobering.

My commonplace booklet

I asked ChatGPT: “How many angels can dance on the head of a pin?” Here’s its reply:

Short answer: it depends — on what you mean by “angel.”

Three ways to answer it:

1) Theological / philosophical: If angels are immaterial (no size) then — mathematically — an infinite number can “dance” on the head of a pin. That’s the usual jokey scholastic point: the question is meaningless unless you fix physical assumptions.

2) Historical: The famous question is a later caricature of medieval scholastic debate, not a literal physics problem asked by medieval theologians.

3) If you force a physical/mathematical interpretation: Use the area of the pinhead and the area occupied by each angel. For a typical pinhead 2.0 mm across, area = π·(1.0 mm)² ≈ 3.1416×10⁻⁶ m². Then • If each angel needs 1 mm² (1.0×10⁻⁶ m²) → ≈ 3.14 angels (so practically 3). • If each needs 0.1 mm² (1.0×10⁻⁷ m²) → ≈ 31 angels. • If each needs 0.01 mm² (1.0×10⁻⁸ m²) → ≈ 314 angels. • If each needs 0.001 mm² (1.0×10⁻⁹ m²) → ≈ 3,142 angels.

Formula used: N = (area of pinhead) / (area per angel).

So — short, playful reply: “As many as you allow them to be.” If you want, tell me what pin diameter and what angel size you imagine and I’ll give the exact number.

Feedback

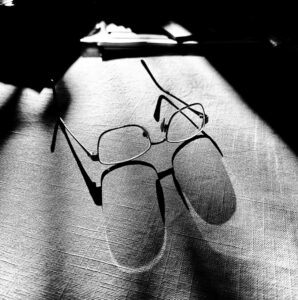

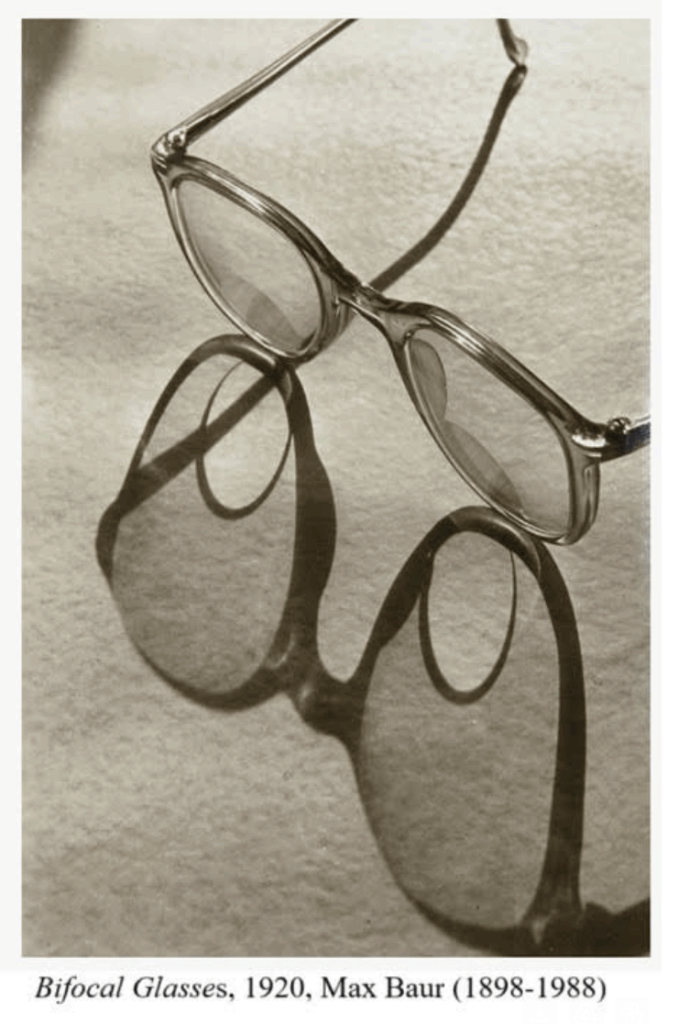

My quasi-surrealist pic of spectacles in sunlight in Wednesday’s edition, prompted Kevin Cryan to remind me that “there is nothing new under the sun”. As proof he pointed to this lovely 1920 work by Max Baur.

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 5am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!