- Jennifer Pahlka, who heads Code for America, was invited to the White House ‘tech summit’. Here’s her low key but interesting report.

- In a few years, no investors are going to be looking for AI start-ups. Guess why. (Hint: investors are always looking for the New New Thing.)

- Is the Internet Broken?. Good discussion from the Aspen Ideas Festival. Answer: No — the Internet isn’t broken. It’s still doing what it was designed to do, namely to connect computers to other computers. It’s those computers — and what people do with them — that’s the problem. Two guys on the panel — Howard Shrobe from MIT and Milo Medin (ex-NASA, now at Google) — really know their stuff.

- To tackle Google’s power, regulators have to go after its ownership of data. Excellent piece by Evgeny Morozov from yesterday’s Observer.

- Internet regulation: is it time to rein in the tech giants?. Long and thoughtful piece by Charles Arthur.

- How contemporary accounts of the Watergate years read in the Trump era.

Monthly Archives: July 2017

What Steve (Jobs) hath wrought

My Observer column on the tenth anniversary of the iPhone:

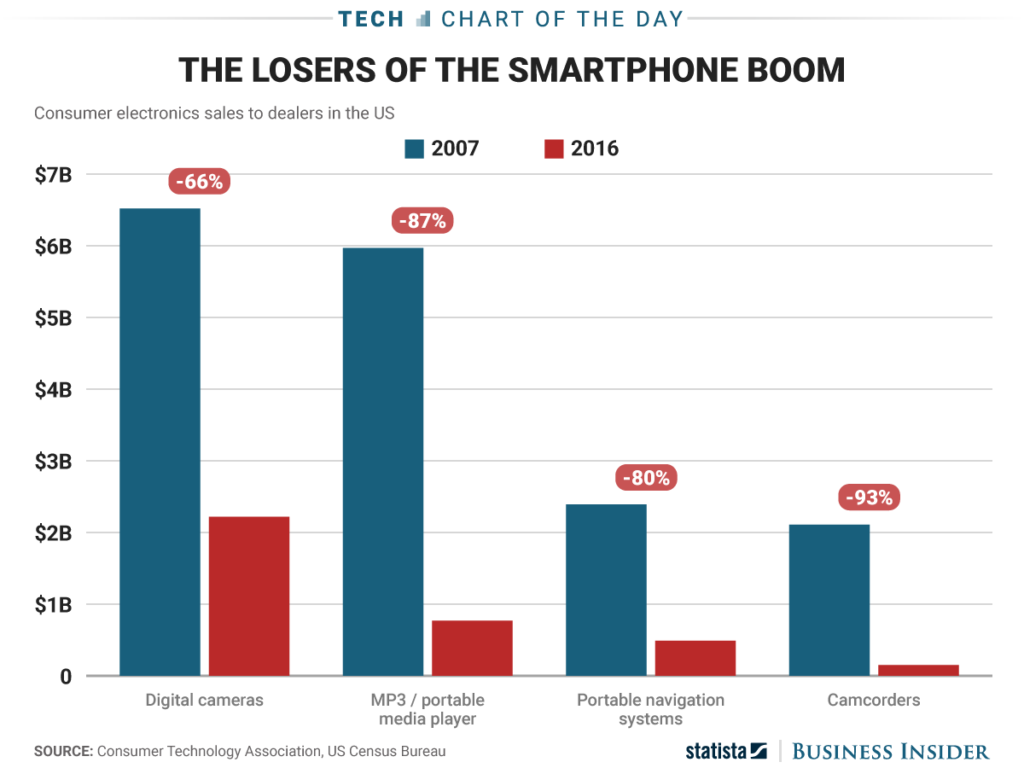

The iPhone made Apple the world’s most valuable company (with a market capitalisation of $771.44bn when I last checked) but, in a way, that’s the least interesting thing about it. What’s more significant is that it sparked off the smartphone revolution that changed the way people accessed the internet. Steve Jobs’s seminal insight was that a mobile phone could be a powerful, networked handheld device which could also be used to make voice calls. Turning that insight into a marketable reality was a remarkable achievement – commemorated last week by the Computer History Museum in a fascinating two-hour series of recorded conversations with the engineers who built the phone.

The result of this revolution is a world in which most people carry their internet connection around in their bags and pockets. It’s a world of ubiquitous connectivity in which people are never offline and are increasingly addicted to their devices. It’s got to the point where someone has coined a new term – smombies (zombies on smartphones) – to describe pedestrians who walk into obstacles because they are looking at screens rather than at where they’re going…

Paranoia in the Valley

My Observer piece about US reaction to the Google fine:

The whopping €2.4bn fine levied by the European commission on Google for abusing its dominance as a search engine has taken Silicon Valley aback. It has also reignited American paranoia about the motives of European regulators, whom many Valley types seem to regard as stooges of Mathias Döpfner, the chief executive of German media group Axel Springer, president of the Federation of German Newspaper Publishers and a fierce critic of Google.

US paranoia is expressed in various registers. They range from President Obama’s observation in 2015 that “all the Silicon Valley companies that are doing business there [Europe] find themselves challenged, in some cases not completely sincerely. Because some of those countries have their own companies who want to displace ours”, to the furious off-the-record outbursts from senior tech executives after some EU agency or other has dared to challenge the supremacy of a US-based tech giant.

The overall tenor of these rants (based on personal experience of being on the receiving end) runs as follows. First, you Europeans don’t “get” tech; second, you don’t like or understand innovation; and third, you’re maddened by envy because none of you schmucks has been able to come up with a world-beating tech company…

So who decides if someone is a journalist or not?

Very interesting snippet in Sue Halpern’s thoughtful NYRB review of Laura Poitras’s film about Julian Assange:

The danger of carving off WikiLeaks from the rest of journalism, as the attorney general may attempt to do, is that ultimately it leaves all publications vulnerable to prosecution. Once an exception is made, a rule will be too, and the rule in this case will be that the government can determine what constitutes real journalism and what does not, and which publications, films, writers, editors, and filmmakers are protected under the First Amendment, and which are not.

This is where censorship begins. No matter what one thinks of Julian Assange personally, or of WikiLeaks’s reckless publication practices, like it or not, they have become the litmus test of our commitment to free speech. If the government successfully prosecutes WikiLeaks for publishing classified information, why not, then, “the failed New York Times,” as the president likes to call it, or any news organization or journalist? It’s a slippery slope leading to a sheer cliff. That is the real risk being presented here, though Poitras doesn’t directly address it.