There’s an interesting post on Quartz about the fragility of a complex system — in this case the Web. The gist of it is that there’s a small piece of Javascript code written by a 28-year-old open source programmer named Azer Koçulu which was hosted on npm, a well-known package-manager for open source javascript code.

As Quartz tells it,

One of the open-source JavaScript packages Koçulu had written was kik, which helped programmers set up templates for their projects. It wasn’t widely known, but it shared a name with Kik, the messaging app based in Ontario, Canada. On March 11, Koçulu received an email from Bob Stratton, a patent and trademark agent who does contract work for Kik.

Stratton said Kik was preparing to release its own package and asked Koçulu if he could rename his. “Can we get you to rename your kik package?” Stratton wrote.

There then followed some fairly acrimononious back-and-forth between Stratton and Koçulu, who was irritated by a private company wanting him to rename his package.1 In the end, Stratton went to npm, who agreed to take his package down.

A few days later, JavaScript programmers around the world began receiving a strange error message when they tried to run their code. For some, the issue was severe enough to keep some of them from updating apps and services that were already running on the web.

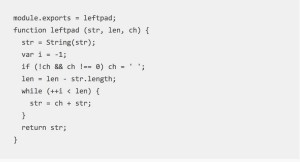

It turned out that lots of applications actually needed Mr Koçulu’s tiny snippet of code if they were to function properly.

This is just the latest illustration of one of the most conveniently-overlooked aspects of the Web (and indeed of the whole Internet), namely that many commercially-profitable enterprises are built on the back of open source code — stuff written by programmers who are willing to put their work into the public domain.

This is one of the dirty secrets of digital technology: some Internet fortunes are the result of free riding on the backs of other people’s (unpaid) work.

-

To be fair to Mr Stratton, he offered to buy the name ‘kik’, but Mr Koçulu priced it at $30k, which I guess is a bit steep for 11 lines of Javascript. ↩