Daily Archives: April 19, 2015

The Eurosceptic UK

If a referendum were held on the UK’s membership of the EU with the options being to remain a member or withdraw, how do you think you would vote?

Would definitely vote to leave the EU = 28% Would probably vote to leave the EU = 18% Would probably vote to remain in the EU = 20% Would definitely vote to remain in the EU = 18% Don’t know = 17%

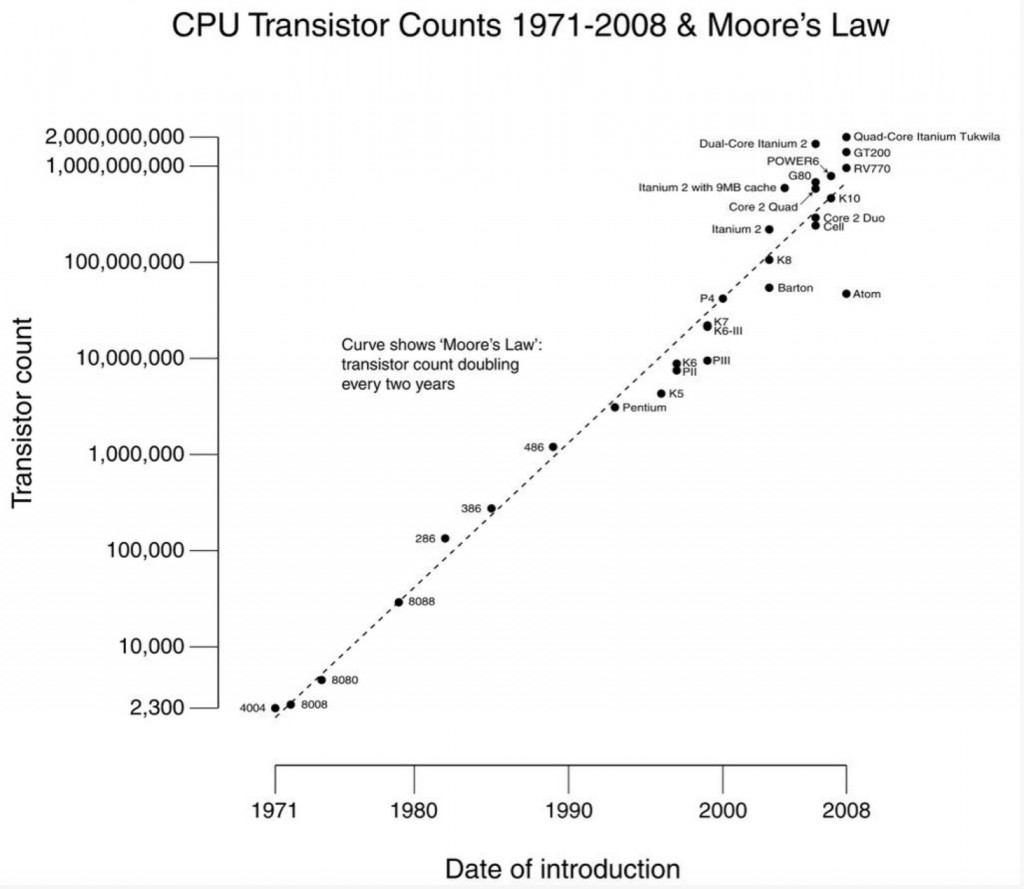

Moore’s Law in a picture

Whenever I lecture on the implications of Moore’s Law I find myself talking about the ‘wheat and the chessboard’ fable. One way of thinking about Moore is that if a problem simply needs more computing power to be solved, then consider it solved.

HT to Ian Yorston for the image.

So can software handle your emotions?

Interesting piece by Zeynep Tufecki in the NYT. She starts with the news that

A robot with emotion-detection software interviews visitors to the United States at the border. In field tests, this eerily named “embodied avatar kiosk” does much better than humans in catching those with invalid documentation. Emotional-processing software has gotten so good that ad companies are looking into “mood-targeted” advertising, and the government of Dubai wants to use it to scan all its closed-circuit TV feeds.

Before buying or using any software, consumers increasingly rely on detailed reviews to ensure they are making the right choice. With the rise of emotion-detection software, this trend has extended beyond mere functionality and into how technology impacts user experience.

For those considering new products, it’s wise to explore resources like https://www.digitalproductsdp.com/ to get a clearer picture of the software’s capabilities and limitations. This ensures that consumers are well-informed and prepared to navigate the complexities of emerging technologies.

What this means is that

Machines are getting better than humans at figuring out who to hire, who’s in a mood to pay a little more for that sweater, and who needs a coupon to nudge them toward a sale. In applications around the world, software is being used to predict whether people are lying, how they feel and whom they’ll vote for.

To crack these cognitive and emotional puzzles, computers needed not only sophisticated, efficient algorithms, but also vast amounts of human-generated data, which can now be easily harvested from our digitized world. The results are dazzling. Most of what we think of as expertise, knowledge and intuition is being deconstructed and recreated as an algorithmic competency, fueled by big data.

But computers do not just replace humans in the workplace. They shift the balance of power even more in favor of employers. Our normal response to technological innovation that threatens jobs is to encourage workers to acquire more skills, or to trust that the nuances of the human mind or human attention will always be superior in crucial ways. But when machines of this capacity enter the equation, employers have even more leverage, and our standard response is not sufficient for the looming crisis.

Googlepower challenged? Not really

This morning’s Observer column:

To those of us who follow these things, the most interesting thing about Thursday’s announcement is the way it highlights the radical differences that are emerging between European and American attitudes to internet giants. The Wall Street Journal recently revealed that the US Federal Trade Commission had investigated similar claims about Google’s abuse of monopoly power in 2012 and that some of the agency’s staff had recommended charging the company with violating antitrust (unfair competition) laws. But in the end, the FTC backed off.

Now it turns out that its staff had been in regular communication with the European commission’s investigators in Brussels, which means that the Europeans knew what the Americans knew about Google’s activities. But the commission has acted, whereas the FTC did not. Why?