To Burnham Market, the poshest small town in England, for lunch. It’s still the lovely place I remember from when we used to go there two decades ago, but has gone spectacularly up-market — to the point where it now resembles nothing so much as Chelsea-on-Sea. Streets choc-a-bloc with Porsche Cayman and Toucan Touareg SUVs, boutiques selling trinkets that cost more than the Gross National Product of Ecuador, cheery gels with names like Camilla and Eugenie and Amanda wearing green wellies — you can imagine the scene. But still, unaccountably, charming. I was reminded of the time, years ago, when a good friend of mine dreamed of buying a little house in Burnham Market and settling down to a career writing scandalous novels. (She never managed it, and became an academic instead. But today I imagined her casting an ironic eye on the visiting Yuppies, and using them as characters in a comic novel.)

Our plan was to lunch in the Hoste Arms, but given that (a) we arrived at 1pm, (b) it was wet and cold (and (c) the middle of the holiday season to boot) we should have known better: it was heaving with lunchers. So we found a small cafe and had lovely pea soup and sandwiches instead.

Our plan was to lunch in the Hoste Arms, but given that (a) we arrived at 1pm, (b) it was wet and cold (and (c) the middle of the holiday season to boot) we should have known better: it was heaving with lunchers. So we found a small cafe and had lovely pea soup and sandwiches instead.

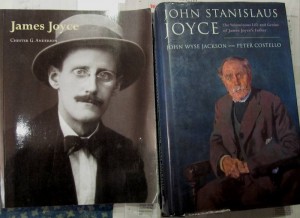

And then we stumbled on the loveliest little secondhand bookshop which had the best collection of biographies I’ve seen in a while — including Chester Anderson’s short illustrated biography of Joyce and the fascinating biography that John Wyse Jackson and Peter Costello wrote of John Joyce, James’s reprobate of a father. I walked out clutching both, and only £11 poorer. Bliss.