The toughest question a venture capitalist can ask a company seeking finance is “what happens if Google decides to move in on your turf?” (Thus far, nobody has come up with a good answer to that question, though we live in hope.) Skype, the VoIP company bought by eBay for an unconscionable sum some years ago, has just encountered that moment. Late yesterday I noticed a little red notice on the top of my Gmail screen saying “New Video Chat!” — Google chat had just been upgraded to handle video. And so, after a quick install and restart of the browser, it has. The guys who unloaded Skype onto eBay and pocketed the loot must be grinning from ear to ear today.

Daily Archives: November 16, 2008

How to regulate

Mark Shuttleworth is in favour of regulated capitalism. But he argues that regulation has to be done properly. Here are his guidelines.

Good regulation is very hard. Over the years I’ve interacted with a few different regulatory authorities, and I sympathise with the problems they encounter.

First, to be an effective regulator, you need superb talent. And for that you need to pay – talent follows the money and the lights, whether we like it or not, so to design a system on other assumptions is to design it for failure. My ideal regulator is an insightful genius working for the common good, but since I’m never likely to meet that person, a practical goal is to encourage regulators to be small but very well funded, with key salaries and performance measures that are just behind the industries they are supposed to regulate. Regulators must be able to be fired – no sense in offering someone a private sector salary and public sector accountability. Unfortunately, most regulators end up going the other way, hiring more and more people of average competence, that they become both expensive and ineffective.

Second, a great regulator needs to be independent. You’re the guy who tells people to stop doing what will hurt society; it’s very hard to do that to your friends. A regulatory job is a lonely job, which is why you hear so many stories of regulators being wined and dined by the industries they regulate only to make sure they don’t look too hard in the back room. A great regulator needs to know a lot about an industry, but be independent of that industry. Again, my ideal is someone who has made a good living in a sector, knows it backwards, can justify their high price, but wants to make a contribution to society.

Third, a great regulator needs to have teeth and muscle. It has been very frustrating for me to watch the South African telecomms regulator get tied up in court by Telkom, and stymied by government department inadequacy. Regulators need to be able to drive things forward, they need to be able to change the way companies behave, and they cannot rely on moral suasion to do so.

And fourth, a regulator has to make very tough decisions about innovation, which amount to venture capital decisions – to make them well, you have to be able to tell the future. For example, when an industry changes, as all industries change, how should the rules evolve? When a new need for society is identified, like the need to address climate change early and systemically, how should the rules evolve? Regulators need to move forward as fast as the industries they regulate, and they need to make decisions about things we don’t yet understand. And even when you regulate, you may not be able to stop an impending crisis. It’s very easy to criticize Greenspan for his light touch regulation on hedge funds and derivatives today, but it’s not at all clear to me that regulation would have made a difference, I think it would simply have moved the shadow global financial system offshore.

So regulation is extremely difficult, but also very much worth investing in if you are trying to run a healthy, vibrant, capitalist society.

Spot on.

Why he blogs

One of my favourite bloggers is Willem Buiter. He’s just written a lovely post explaining why he blogs.

To all those readers of this blog who have requested shorter, snappier, less technical and abstruse postings, the following. I write this blog for me, not for my readers. Writing things down is the only way for me to communicate effectively with myself about complex issues. By doing this writing in the form of a blog, I gain the option of taking on board the comments and criticism of those who read my scribblings and feel compelled to respond to it. I gain this benefit at the cost of having to plough through a lot of stuff that makes little or no sense, in order to uncover the few pearls hidden among the swine. There are minor vanity/ego rents to having people read what I write, and my consulting income may receive an indeterminate boost from these activities. But all that is secondary to my need to write. I don’t know something unless I have written it down.

I started this blog quite independently, at http://maverecon.blogspot.com/. I was invited by the Financial Times to move my blog to their site. Because of the likelihood of greater vanity/ego rents and the possibility of more frequent intelligent feedback through wider readership, I accepted this invitation. When the FT lose interest, I will go private again. I don’t get paid for this blog.

Attaboy! Echoes of my own attitude to the question.

Google as a predictor

Following on from this post and today’s Observer column, I’ve had some feedback asking how one might go about using Google queries as forward indicators of economic developments. The answer is that I don’t know, but it probably hinges on finding the right search queries to map. Here are some experiments I’ve done.

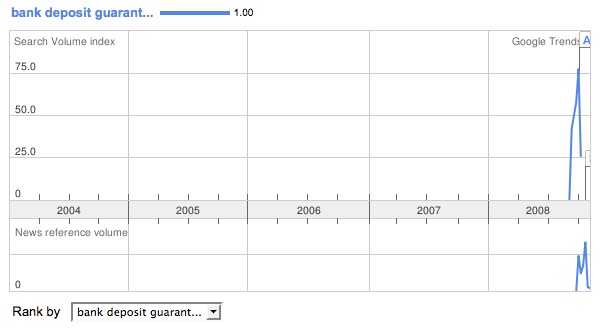

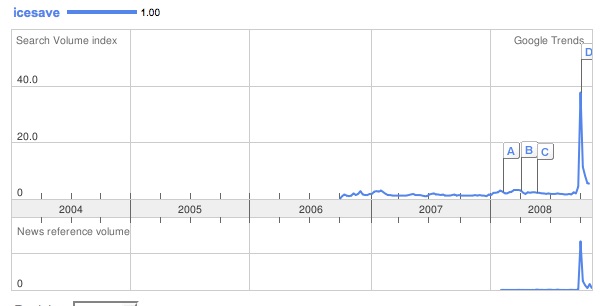

This suggests that people weren’t really concerned about bank deposit guarantees until August 2008. I don’t believe this, so perhaps this is the wrong search term to be tracking.

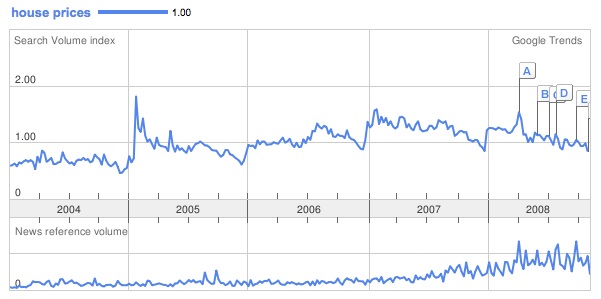

This suggests that the peak of interest in house prices occurred in 2005 and is now in gentle decline. This might indicate that this search term is a token for general curiosity (“wonder why our house is worth at the moment?”) rather than alarm. It’s interesting to compare this with the chart for ‘negative equity’ below.

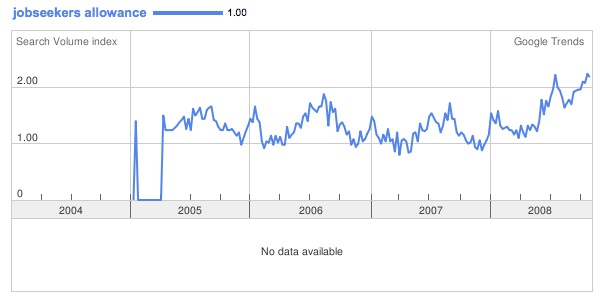

This has a regular annual cycle but is now clearly on the rise. Again, it’s not clear that it has much predictive power.

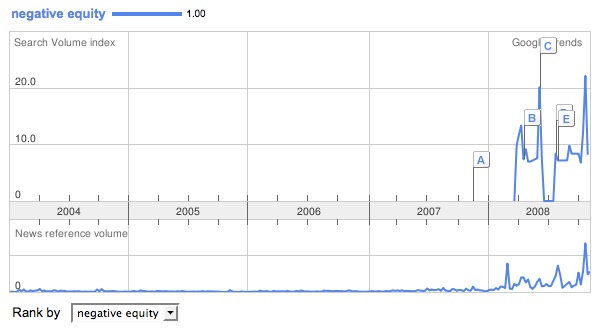

Speaks for itself, I think.

Ditto.

As I say, the trick would be to identify search terms which would give an indication of what people know or suspect about their organisational future.

There’s nothing terribly systematic about this — I was just trying to think of search terms that might reveals what people were thinking as they realise that they face an uncertain future.

Tony Hirst, who is the nearest thing to a wizard with Google data that I know, has some interesting things to say about the topic. He’s also knowledgeable about the limitations of the Google data.

The predictive power of search engine queries

This morning’s Observer column…

The most interesting aspect of the Google data, however, was revealed in a chart which compared flu queries with ‘objective’ data on incidence of the disease compiled by public health authorities. The chart suggests that the search data accurately reflects incidence – but is current rather than lagged. (The official statistics take about two weeks to collate.)

This suggests other possibilities – for example in macroeconomic management. Everyone I know in business has known for months that the UK is in recession, but it’s only lately that the authorities have been in a position to confirm that – because the official data always lag the current reality. So policymakers are in the situation of someone trying to drive a car which has a blacked-out windscreen. The driver’s only view of the road is a via TV monitor showing what was happening 10 seconds ago. How long would you give the driver before he hits a wall? We need to raise our game, and maybe intelligent use of the net offers us a way of doing it.

Depth of field

One of the delights of the Nikon D700 is that all my old Nikon glassware has come back into its own. This was taken earlier this evening with the ancient 50mm f1.2 lens at full aperture.