Riverside

Eastern bank of the Rhone in Arles on a peaceful Summer evening.

Quote of the Day

”When you stop doing things for fun you might as well be dead.”

- Ernest Hemingway

He was as good as his word.

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Handel | Water Music | Suite No. 2 in D Major, HWV 349: II.

I’m married to a keen gardener who is distressed by the current drought. So I offer this as a feeble alternative to attempting a rain dance.

Long Read of the Day

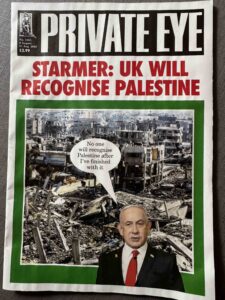

Trump’s Apprentice

If you think that, however unhinged or despicable things are in Washington D.C., it doesn’t affect us here in the UK, then think again — as this fine piece of reportage by Sam Bright makes clear.

When Donald Trump took the oath of office, he made a promise to his bank account – to use the powers of the presidency to enrich the Trump dynasty.

Even in the space of a few short months, according to The New Yorker, Trump has executed his plan with ruthless efficiency, making an eye-watering $3.4 billion. Public service has been supplanted by private revenue. Trump has given a masterclass in how to wrap personal enrichment in the flag and call it patriotism.

Across the Atlantic, Nigel Farage has been taking notes. Since entering Parliament in July 2024, the GB News host and part-time MP has pulled in over £1 million a year from non-parliamentary ventures. He’s even been paid £189,300 for a gold-bullion ambassadorship that requires four hours of work a month.

Farage’s desire to merge politics with personal gain seems to have grown since his theatrical ride in the gold lift of Trump Tower the morning after the 2016 US election…

Worth pondering, now that Reform is polling ten points ahead of Labour at the moment.

My commonplace booklet

Would you pay $200,000 to look half your age?

My eye was caught by a sharp piece by Emma Jacobs in the weekend edition of the Financial Times. It’s about the staggering efforts that members of the 0.01% set are now making to deny that they are getting older.

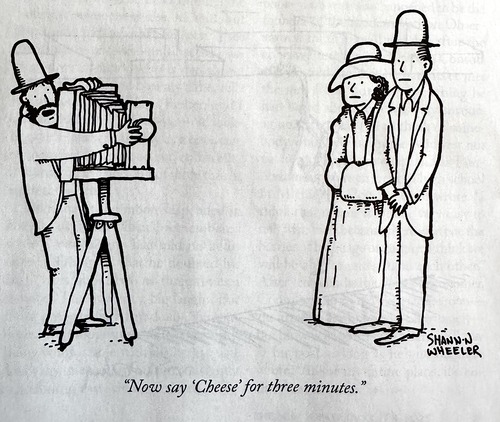

It seems that that old staple, the facelift, is now being given,

well, a facelift. While there is no single “magic” facelift, advances in technique now focus on lifting and tightening the lower part of the face by working with the superficial muscular aponeurotic system (SMAS). This is a key layer involved in facial movement and support.

According to London aesthetics doctor Jonny Betteridge, “By repositioning the SMAS rather than just tightening skin, surgeons can achieve results that look more natural and last longer.”

The deep-plane facelift goes further, he adds. “By releasing and lifting tissue beneath the SMAS, it can provide more significant improvement to the mid-face and nasolabial folds in the right patients. This deeper approach can deliver a more comprehensive lift without an over-tightened appearance.”

Note that this cove is an “aesthetics doctor”. He and his mates have

also learnt to combine facelifts well with other procedures like blepharoplasty (eyelid surgery), fat transfers and brow lifts to achieve more balanced and “harmonious results”. Having one area rejuvenated and another beside it untouched might draw attention to something being done, she says. Furthermore, the abilities of the practitioner are key, with an A-list coterie of doctor names emerging. Betteridge observes “a clear trend towards refreshed and sculpted looks that often result from discreet and highly skilled surgical techniques”.

Of course, this stuff doesn’t come cheap. It seems that A-list celebrities usually turn to expensive surgeons for deep-plane facelifts, which cost more than an SMAS facelift, with prices ranging from $100,000 in New York and Los Angeles, even surpassing $200,000, according to some reports.

We’re living in Gilded Age 2.0, much of it funded by obscene wealth created by tech companies. So maybe Silicon Valley needs a rebrand, or at least a breast implant: Silicone Valley.

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 5am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!