Anyone home?

A neighbour’s lovely cat, who often patrols the locality to check up on who’s up and about.

Quote of the Day

”I had lunch with a chess champion the other day. I knew he was a chess champion because it took him twenty minutes to pass the salt”.

- Eric Sykes

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Joseph Haydn | Cello Concerto in C Major (1st mvt. Moderato) | JY Ahn

Long Read of the Day

Beware the Oligarchs’ Two Bubbles

Robert Reich on the AI and crypto bubbles in which we are currently immersed.

The flood of money into these two opaque industries — AI and crypto — has propped up the U.S. stock market and, indirectly, the U.S. economy.

AI and crypto have created the illusion that all is well with the economy — even as Trump has taken a wrecking ball to it: raising tariffs everywhere, threatening China with a 100 percent tariff, sending federal troops into American cities, imprisoning or deporting thousands of immigrants, firing thousands of federal workers, and presiding over the closure of the U.S. government.

When the AI and crypto bubbles burst, we’ll likely see the damage Trump’s wrecking ball has done.

I fear millions of average Americans will feel the consequences — losing their savings and jobs.

I don’t know about crypto, but the AI bubble looks to me like the real deal, and I wonder what will be left when it bursts.

Books, etc.

This looks interesting. It was recommended by Andrew Curry (Whom God Preserve). It describes a world, he says, where

Climate change has got worse, and governments have shrunk. To the extent that government works at all, it works in the service of a collection of anonymous corporations whose interests are protected by aggressive intellectual property legislation and their own privately maintained police forces. In the countryside, many people live in ‘corpo-towns’ maintained by the corporations. (For those outside of their protection, ‘corpo’ is a term of disdain, or abuse.) There’s a large active underclass that looks after itself outside of the mainstream economy, living in places that are in a kind of liminal space, a nomansland, between city and country. Violence is never far below the surface.

AI manages a lot of services, and security, and confusing it about who you are as you go across town is an important part of surviving in this world…

One of the reasons why more people don’t worry about the direction of travel in our contemporary world is that we all suffer from imaginative failure — our inability to project forward. That’s why we need creative artist and novelists who can see round some of the corners that lie ahead. Many moons ago, two writers — George Orwell and Aldous Huxley — put forward two different visions on how things would pan out. Orwell thought we would be destroyed by the things we fear; Huxley that we would be undone by the things that delight us. As it happened, both were right: we got two dystopias for the price of one.

Feedback

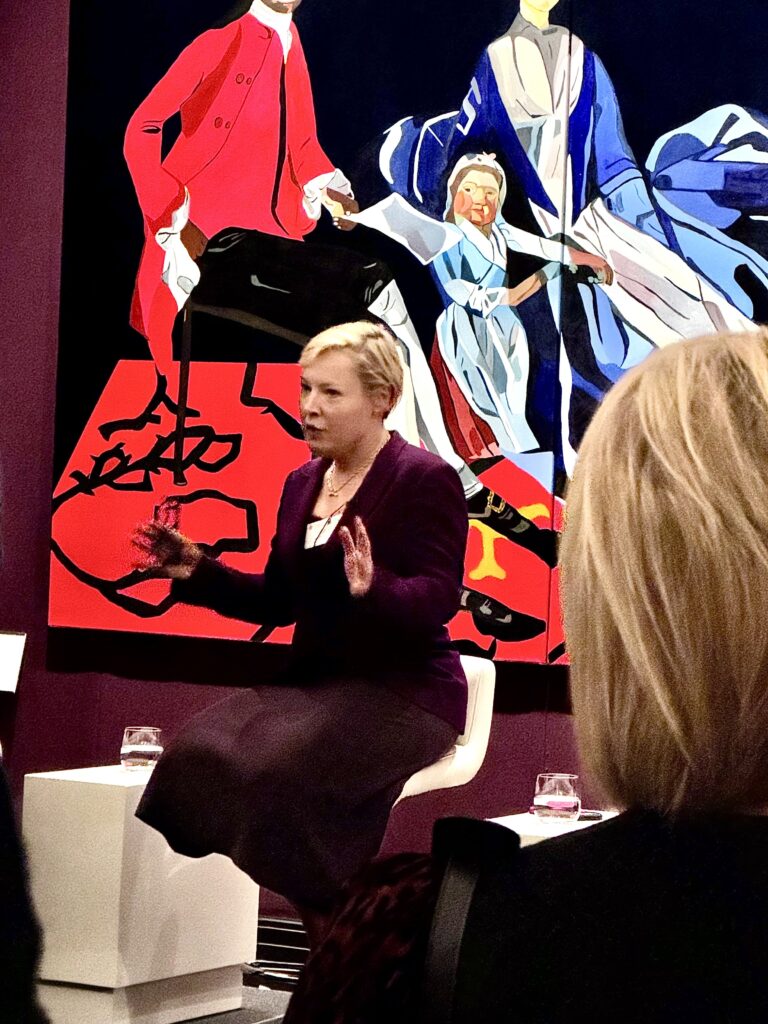

Thanks to Diane Coyle and Robert Hanks for identifying the picture behind Gillian Tett in Monday’s photograph.

It’s Joy Labinjo’s An Eighteenth-Century Family.

Robert writes that it’s

part of the rehang a couple of years ago which added a number of works by women (mostly brought out of the vaults) and POCs (mostly new commissions). It’s an imaginary portrait of the writer and campaigner for abolition Olaudah Equiano and his family: he married Susannah Cullen, a Soham girl. I’ve a vague idea that it’s based on a portrait by Gainsborough of his own family. The rehang isn’t entirely successful, imo, but I do like this one.

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 5am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!