One way of growing an Iris

In the college garden.

Quote of the Day

”What is the difference between a Nazi and a dog? The Nazi lifts his arm.”

- Viktor Borge

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Mozart | Don Giovanni | K. 527 | Act 1 | “Là ci darem la mano”| (Live)

How is it that the devil generally has the best tunes?

Long Read of the Day

Populism is an information problem, but not in the way that you think

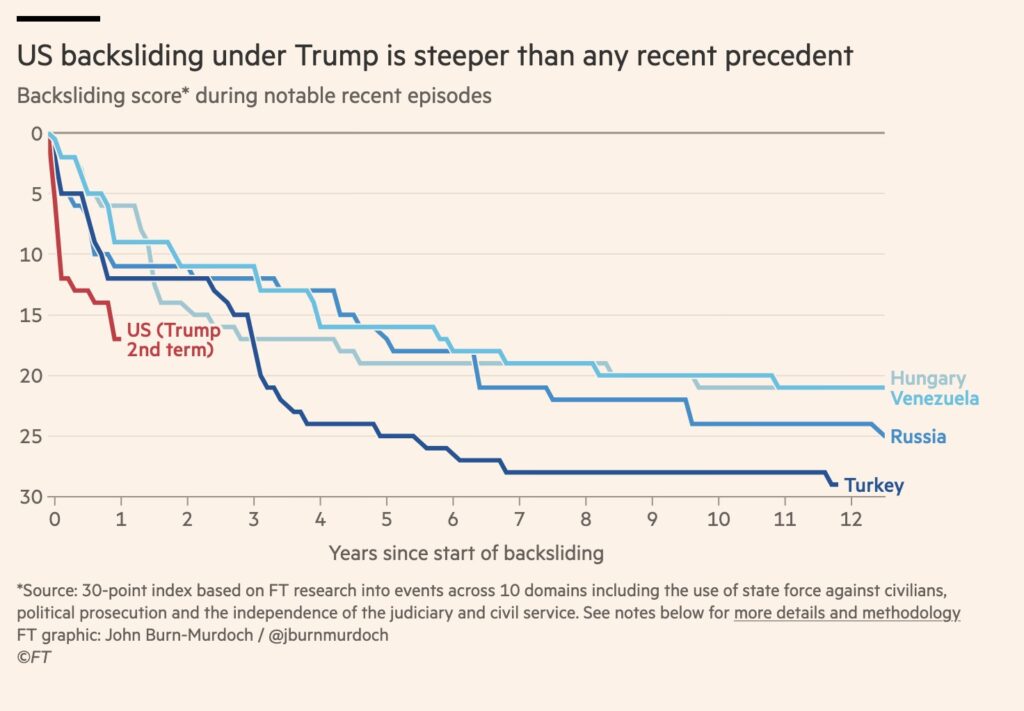

One of the frustrating things about living in the UK at the moment is the way the country seems to be terminally stuck. It has a Labour government with a huge parliamentary majority — big enough to qualify as the ”elective dictatorship” that the Attlee government used to start the reconstruction of a war-exhausted country — and yet it’s blundering around devoid of a vision or even a good story. Part of that is a legacy of Brexit, but the bigger reason is that the UK is a case study in a much wider problem — how post-war liberal democracy has failed its citizens.

Democratic revival has to start with a frank acknowledgement of this failure. And for that we need an analytical lens through which to view it, which is why this essay by Andrew Curry in yesterday’s edition of his Just Two Things Substack was such a delight. He draws on Dan Davies’s magnificent book, The Unaccountability Machine: Why Big Systems Make Terrible Decisions to make his point.

All of this reminded me of Dan Davies’ book The Unaccountability Machine, about the principles of management cybernetics developed by Stafford Beer (more about the book on Just Two Things here), In it, he applies some of the learning to the rise of populism:

“People are overloaded with information that they can’t process; the world requires more decisions from them than they’re capable of making, and the systems that are meant to shield them from that volatility have stopped doing the job. (p.253)

Although it is hard to define ‘overload’ in this context, you can see the signs:

“you can easily observe the difference between a human being that is coping and one that is overloaded”. (p.251)

Often these signs are qualitative: Lexi, for, example, a mother of two, who told John Harris that she

“holds down three different jobs – as a care support worker, a dinner lady and a cleaner – and says she is just about holding everything together”.

But there are not only qualitative signals. The work of Anna Case and Angus Deaton showed a sharp quantitative increase in what they called “deaths of despair” in the United States, from alcoholism, opiate addiction and suicide. The qualitative insight here was in connecting these different data categories in a single frame.

But one of the bigger problems here is that in modern states, even in democracies, the information channels between governments, political parties, and citizens don’t carry very much information:

”The only kind of communication that such a constrained channel can carry is a scream: the signal that passes through the levels of control and announces that something has gone wrong which threatens the integrity of the system itself. This is why there was a family resemblance between the ‘populist’ movements that sprang up in the 2010s… The medium itself is the message: what liberal society ought to be responding to is the fact of mass distress, not its content.” (pp250-51, emphasis in original)

I’ve always thought that the Brexit vote was a scream in that sense. In the 2015 general election in Britain, for example, nearly 4m people voted for UKIP — the “Leave’ party. And got precisely one MP (out of 650) because of the country’s First-Past-The-Post system. The Brexit referendum, however, gave them a vote that would matter — a binary choice — and they took it.

Do read on. Dan Davies’s brilliant insight was that cybernetics offered a novel way of thinking about our present difficulties. This is music to the ears of an engineer like me. And not just me: it has also struck Henry Farrell, who is a great political scientist and one of the smartest people around.

My commonplace booklet

From Brad Delong…

FEB 23, 2026

I do not know how to handle the intellectual crisis tsunami now coming down on me from the creation, development, and societal consequences of MAMLMs—Modern Advanced Machine-Learning Models—other than to find a floatation device, hang on for dear life, and start kicking as fast as I can. But I do know some things: As MAMLMs make text-extrusion five times faster, the real crisis moves to reading, filtering, and not going insane. “Prompt whispering” is theater; “context engineering is the work”. Stop treating language models like minds and start treating them like very fancy calculators wired to very large libraries. Your AI is not your friend, therapist, co‑author, or co-pilot; it is a token‑production machine. If you feed it a wise string of tokens, wise tokens will come out. If you feed it tokens from a stupid conversation, stupid tokens will come out…

He also quotes this from Mike Taylor:

Memory is frequently described as ChatGPT’s “killer feature.” Many people tell me they can’t switch to Gemini or Claude because the OpenAI tool “knows them so well.”

I have memory turned off.

The memory feature allows ChatGPT to save and recall information it thinks is important about you, as well as reference past chats to shape its responses. While I can see how this could make a “helpful assistant” more helpful, I don’t use it.

I want unbiased results from ChatGPT, based on context that I carefully curated and put in the prompt, so I know how it made its decision. With memory, anything from your past chats could affect the results in ways that are hard to predict.

This squares with my experience.

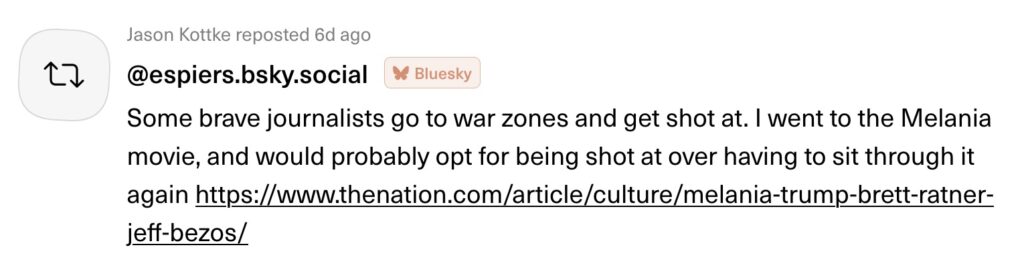

Linkblog

Something I found while drinking from the Internet firehose

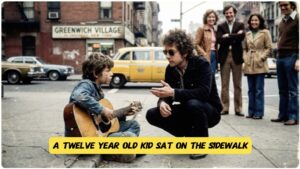

Screenshot

The day Bob Dylan came on a street kid playing a broken guitar in New York. And stopped to talk to him

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 5am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!