Skype interview by andrewkeen on Vimeo.

Category Archives: Intellectual Property

Google’s bid for our literary heritage

This morning’s Observer column.

If you have any free brain cells next Tuesday, spare a thought for Denny Chin. He is a judge on the US district court for the southern district of New York. And he has the job of deciding a case which has profound implications for our culture.

At its centre is a decision about how we will access printed books in the future. And, as you might guess, Google is at the heart of it…

The published version of the column omitted the reference to Professor James Grimmelmann’s terrific commentary on the case. If you’re interested, you can get the pdf from here.

Lord Mandelson’s Dangerous Downloaders Act

My two-pennyworth in today’s Times .

The consultation document says the Carter plan would take too long to implement “given the pressure put on the creative industries by piracy”. Instead, ISPs would be obliged to block access to download sites, throttle broadband connections or even temporarily cut off access for repeat offenders. It is clearly envisaged that the new measures will be bundled into the Bill, which will implement the main proposals of the Digital Britain report.

If that does indeed happen, then the nearest legal precedent is the Dangerous Dogs Act of 1991, an unworkable statute passed in response to tabloid hysteria about pitbull terriers. There’s no evidence that anyone in Lord Mandelson’s department has thought through the implications of giving in to the content industries. For one thing, there are the technical, financial and legal burdens the proposals would put on ISPs, which would be required not only to act as security officers for the entertainment industry, but also to enter the minefield of terminating people’s internet access on grounds that could be questionable in law.

The only people who think this is simple are either industry lobbyists or those who don’t understand it…

Free Thinking

This morning’s Observer column.

The reception accorded to Free has been markedly different from the respectful audience for the Long Tail. The opening salvo came from Malcolm Gladwell, the New Yorker writer who is himself a virtuoso of the Big Idea, as expressed in books such as The Tipping Point and Outliers. He was particularly enraged by Anderson’s recommendation that journalists would have to get used to a world in which most content was free and more and more people worked for non-monetary rewards.

“Does he mean that the New York Times should be staffed by volunteers, like Meals on Wheels?” Gladwell asked icily…

The Gladwell piece is here, by the way.

Saving Texts From Oblivion

Interesting essay by Oxford University Press’s Tim Barton.

At a focus group in Oxford University Press’s offices in New York last month, we heard that in a recent essay assignment for a Columbia University classics class, 70 percent of the undergraduates had cited a book published in 1900, even though it had not been on any reading list and had long been overlooked in the world of classics scholarship. Why so many of the students had suddenly discovered a 109-year-old work and dragged it out of obscurity in preference to the excellent modern works on their reading lists is simple: The full text of the 1900 work is online, available on Google Book Search; the modern works are not.

It’s a very thoughtful, non-doctrinaire piece. “If it’s not online, it’s invisible”, he writes.

While increasing numbers of long-out-of-date, public-domain books are now fully and freely available to anyone with a browser, the vast majority of the scholarship published in book form over the last 80 years is today largely overlooked by students, who limit their research to what can be discovered on the Internet.

On the Google Books ‘agreement’, he writes:

It has taken many months for the import of the settlement to become clear. It is exceedingly complex, and its design — the result of two years of negotiations, including not just the parties but libraries as well — is, not surprisingly, imperfect. It can and should be improved. But after long months of grappling with it, what has become clear to us is that it is a remarkable and remarkably ambitious achievement.

It provides a means whereby those lost books of the last century can be brought back to life and made searchable, discoverable, and citable. That aim aligns seamlessly with the aims of a university press. It is good for readers, authors, and publishers — and, yes, for Google. If it succeeds, readers will gain access to an unprecedented amount of previously lost material, publishers will get to disseminate their work — and earn a return from their past investments — and authors will find new readers (and royalties). If it fails, the majority of lost books will be unlikely ever to see the light of day, which would constitute an enormous setback for scholarly communication and education.

The settlement is a step forward in solving the problem of “orphan works,” titles that are in copyright but whose copyright holders are elusive, meaning that no rightsholder can be found to grant permission for a title’s use. For such books, a professor cannot include a chapter in a course pack for students; a publisher cannot include an excerpt in an anthology; and no one can offer a print or an electronic copy for sale. Making those books available again is a clear public good. Google’s having exclusive rights to use them, as enshrined in the current settlement, however, is not.

If the parties to the settlement cannot themselves solve this major problem, then at a minimum Congress should pass orphan-works legislation that gives others the same rights as Google — an essential step if Google is not to gain an unfair advantage. Despite significant advocacy, Congress has failed to legislate on this issue for 20 years; we at Oxford hope the specter of Google having exclusive rights to use orphan works will spur heightened public debate and Congress to immediate action.

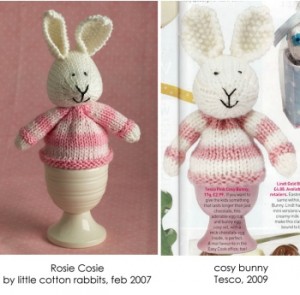

Tesco: every little helps, er, Tesco

Guess how much Tesco paid for the rights to Rosie Cosie?

Then check your estimate here.

(Prediction: the next step will be a letter from Tesco lawyers accusing Julie Williams for using the image of Tesco Cosy Bunny without permission.)

UPDATE: The link to her blog no longer works. Ms Williams has taken her post offline. She explains:

A quiet thank you

I had no idea that things would escalate to such proportions when I wrote about my egg cosy problems earlier today. I need to sleep on the whole matter and consider some of the very valid points that have been raised. This is a matter for me and one that only affects me and my very little business. To see things snowballing from a small and personal matter is a little disconcerting, and the reason I’ve taken my post off-line for now.

Wonder what happened?

Google vs songwriters

Very interesting blog post by Rory Cellan-Jones.

neither Google – YouTube's owners – nor the PRS will give chapter and verse on their previous licensing agreement, but neither are they disputing the size of the payouts. But the problem, in the words of someone close to the negotiations, is that the PRS seems to have signed “a rubbish deal” – at least as far as the songwriters are concerned. And that’s because it was struck when YouTube was in its infancy – oooh two or three years back – and nobody saw it growing into a major force in the music business.

Now the PRS has demanded a rate per stream from YouTube which Google says is just completely unrealistic – and would mean the search firm would lose money every time someone watched a music video.

Mind you, the German songwriters union has apparently looked at what the British are asking for – and demanded a rate 50 times higher.

Later on, Rory cites research by Credit Suisse which claims that Google is losing about $440 million a year on YouTube. It can’t last, folks — enjoy it while you can.

“Misappropriation” vs. Fair Use

The legal basis for a challenge by newspapers to Google is beginning to emerge.

In 1918, the AP was involved in a case called International News Service v. Associated Press. Like current competitor All Headline, INS didn’t actually copy AP’artime scoops off the wire, have a hired hack rewrite the story in his own words, and put out their own version of the breaking news without having to bear all the overhead (not to mention the considerable risk) of sending trained reporters to a war zone. It wasn’t quite copyright infringement, but it sufficiently offended the justices’ sense of fair play that they developed the doctrine of ‘misappropriation’ to cover the immediate copying and dissemination of ‘hot news’ by commercial competitors of a news organization. If such ‘free riding’ were allowed, the judges reasoned, the parasites would always be able to undersell their hosts, to the detriment of journalism in the long run.

It’s not hard to see why AP is concerned now. According to its annual report (PDF), the combination of subscriber attrition and the lower fees they’ve had to adopt to keep that dwindling, cash-strapped client base on board “will result in a revenue decline not seen by the company since the Great Depression.”

The Internet compounds the problem. The RIAA and MPAA can at least try—however ineffectively—to use copyright law to stanch unauthorized copying of their works. But what AP is selling isn’t really the scintillating prose of its writers: it’s fast access to the facts of breaking news. Now, though, a writer for any one of a million websites can read an AP story on the site of a subscribing news organization, write up their own paraphrase of the story, and have it posted—and drawing eyeballs from AP subscribers — within an hour of the original’s going live.

This might just work for AP. It’ll be harder for newspapers to argue, however — except for straight news coverage. I’d be surprised if they could make the argument stick for commentary — which, after all, is what most newspapers do nowadays.

The Digger wants to give up Googlejuice.

Funny to see the Dirty Digger and arch-libertarian Henry Porter climbing onto the same mattress, but life’s like that sometimes. History’s littered with strange alliances. Here’s Forbes.com’s take on it:

Rupert Murdoch threw down the gauntlet to Google Thursday, accusing the search giant of poaching content it doesn’t own and urging media outlets to fight back. “Should we be allowing Google to steal all our copyrights?” asked the News Corp. chief at a cable industry confab in Washington, D.C., Thursday. The answer, said Murdoch, should be, “Thanks, but no thanks.”

Google sees it differently. They send more than 300 million clicks a month to newspaper Web sites, says a Google spokesperson. The search giant is in “full compliance” with copyright laws. “We show just enough information to make the user want to read a full story–the headlines, a line or two of text and links to the story’s Web site. That’s it. For most links, if a reader wants to peruse an entire article, they have to click through to the newspaper’s Web site.”

Later in the piece Anthony Moor, deputy managing editor of the Dallas Morning News Online and a director of the Online News Association is quoted as saying:

“I wish newspapers could act together to negotiate better terms with companies like Google. Better yet, what would happen if we all turned our sites off to search engines for a week? By creating scarcity, we might finally get fair value for the work we do.”

Now that would be a really interesting experiment. If I were the Guardian and the BBC I’d be egging these guys on. It’d provide an interesting case study in how to lose 50% market share in a week or two.

UPDATE: Anthony Moor read the post and emailed me to say that Forbes’s story presented an unduly simplistic version of his opinion:

Just to clarify, I’m not one of those who think Google is the death of newspapers. Quite the contrary, I emphasized to reporter Dirk Smillie that search engines are the default home page for people using the Internet, and as such, direct a lot of traffic to us. That traffic is important. I don’t believe Google is “stealing” our content. And I was being a bit tongue-in-cheek about “turning off” to Google. We don’t matter much to Google. I was musing about what might happen if all news sites turned off for a week. What would people think? Would they survive? (Maybe.) I wasn’t suggesting we block Google from spidering our content. That wouldn’t test the “what if digital news went dark” hypothesis. In any case, none of that will fix our own broken business model.

Google organizes the Web. Something needs to do that. My concern is that they’re effectively a monopoly player in that space. Oh sure, there’s Yahoo, but who “Yahoos” information on the Web? I understand and recognize the revolutionary nature of the link economy, but I’m concerned that it’s Google which defines relevance via their algorithms. (Yes, I know that they’re leveraging what people have chosen to make relevant, but they’re still applying their own secret sauce, which is why we all game it with SEO efforts) and that puts the rest of us in a very subservient position.

I wonder if there isn’t another way in which the Web can be organized and relevance gained that reduces the influence of Google and returns some of the value that Google is reaping for the rest of us? I predict that someday there will be and all this talk of Google’s dominance will be history.

STILL LATER: At the moment, there’s a very low signal-to-noise ration in this debate : everyone has opinions but nobody knows much, and it’d be nice to find some way of extracting some nuggets of hard, reliable knowledge on which we could all agree. An experiment in which major news sources turned off their online presence for a week or two might be useful in that context. And it might enable us to move on from the current yah-boo phase. It would enable us to assess, for example, the extent to which the blogosphere is really parasitic on the traditional news media. My view (for what it’s worth) is that the relationship is certainly symbiotic, but that the blogosphere is more free-standing than print journalists tend to assume. The experiment would shed some light on that.

Will Google be a benign foster-parent? Don’t bet on it

When you think about the way the academic world allowed itself to be hooked by the scientific periodical racketeers, it makes sense to be wary of any commercial outfit that looks like acquiring a monopoly of a valuable resource. The obvious candidate du jour is Google, which is busily scanning all those orphan works (i.e. works whose copyright owners cannot be found) in libraries in order to make them available to a grateful (academic) world. Some people are (rightly) suspicious and are going to challenge the legal settlement which Google negotiated with publishers in the US. At the JISC ‘Libraries of the Future’ event in Oxford last Thursday, Robert Darnton of Harvard (pictures above) said some perceptive things about the potential threats ahead. So it was interesting to see this piece in this morning’s NYT.

These critics say the settlement, which is subject to court approval, will give Google virtually exclusive rights to publish the books online and to profit from them. Some academics and public interest groups plan to file legal briefs objecting to this and other parts of the settlement in coming weeks, before a review by a federal judge in June.

While most orphan books are obscure, in aggregate they are a valuable, broad swath of 20th-century literature and scholarship.

Determining which books are orphans is difficult, but specialists say orphan works could make up the bulk of the collections of some major libraries.

Critics say that without the orphan books, no competitor will ever be able to compile the comprehensive online library Google aims to create, giving the company more control than ever over the realm of digital information. And without competition, they say, Google will be able to charge universities and others high prices for access to its database.

The settlement, “takes the vast bulk of books that are in research libraries and makes them into a single database that is the property of Google,” said Robert Darnton, head of the Harvard University library system. “Google will be a monopoly.”

Yep. I’ve always thought that Google will be Microsoft’s successor as the great anti-trust test for the Obama Administration. I hope the DoJ is tooling up for it.