I’ve always been ambivalent about Christmas. Because my parents were’t very good at celebrations, my childhood experience of the festival was often one of disappointment. When I met Sue, my late wife, I had to change my views because she really loved Christmas and took great delight in every part of it, and our children learned that from her. But I remain acutely aware of the stresses it puts on people who are poor, unhappy or depressed, when the contrast between their own conditions and the glitzy, showy, consumer-driven atmosphere all around is painful. So it was sweet to find this message on one of the main pedestrian bridges across the Cam this Christmas.

Category Archives: Asides

Practice makes perfect

Tyler Cowen, the economist, is one of the most interesting public intellectuals around. His blog is a marvel (and a daily visit for me). His capacity to absorb ideas is remarkable. And he is fearsomely productive. So how, one wonders, does he do it?

This week he shed some light on how he works:

I write every day. I also write to relax.

Much of my writing time is devoted to laying out points of view which are not my own. I recommend this for most of you.

I do serious reading every day.

After a talk, Q&A session, podcast — whatever — I review what I thought were my weaker answers or interventions and think about how I could improve them. I rehearse in my mind what I should have said. Larry Summers does something similar.

I spent an enormous amount of time and energy trying to crack cultural codes. I view this as a comparative advantage, and one which few other people in my fields are trying to replicate. For one thing, it makes me useful in a wide variety of situations where I have little background knowledge. This also helps me invest in skills which will age relatively well, as I age. For me, this is perhaps the most importantly novel item on this list.

I listen often to highly complex music, partly because I enjoy it but also in the (silly?) hope that it will forestall mental laziness.

I have regular interactions with very smart people who will challenge me and be very willing to disagree, including “GMU lunch.”

Every day I ask myself “what did I learn today?”, a question I picked up from Amihai Glazer. I feel bad if I don’t have a clear answer, while recognizing the days without a clear answer are often the days where I am learning the most (at least in the equilibrium where I am asking myself this question).

One factor behind my choice of friends is what kind of approbational sway they will exercise over me. You should want to hang around people who are good influences, including on your mental abilities. Peer effects really are quite strong.

I watch very little television. And no drugs and no alcohol should go without saying.

Footnote ‘GMU’ = George Mason University, where he works.

Sex sells, apparently

Well, what do you know? the best-selling book over the last decade was E.L. James’s 50 Shades of Grey, which which sold 15.2 million copies from 2010 through 2019. It was originally self-published as a Kindle ebook and print-on-demand publication in June 2011; the publishing rights were acquired by Vintage Books in March 2012. Smart move. I wonder what they paid for them.

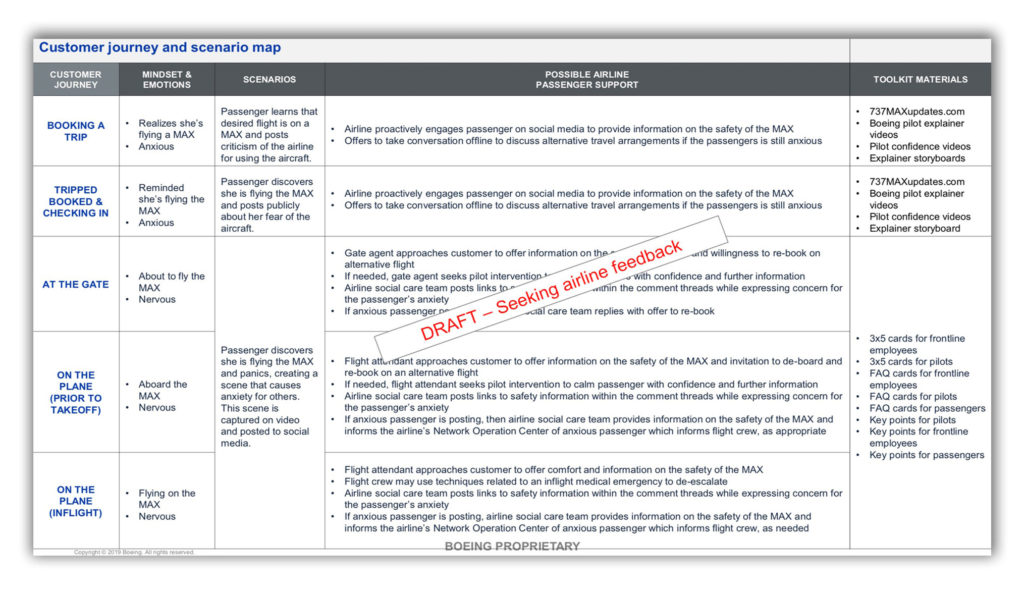

Boeing’s idea of reassurance

Source: New York Times

Boeing’s 737MAX remains grounded (rightly) as the company struggles to overcome the design flaw that caused two crashes that killed everyone on board. In the meantime, Boeing has been surveying airline passengers across the world to assess their thoughts about flying in the MAX once it gets certification. The news is not good, according to this report in the New York Times: people are nervous about flying in the plane. In order to get ahead of the problem, Boeing has been preparing draft briefing materials for airline staff giving guidance on how to soothe and reassure nervous passengers. Above is a draft of the crib-sheet that’s been obtained by the Times.

As you’d expect, it’s an exercise in consumer manipulation.

This has a personal dimension for me. The place to which I most often fly is Ireland. And the only way to get there from Stansted, my local airport, is via RyanAir. But RyanAir plans to replace its existing fleet of Boeing aircraft with 737MAXs. So will I trust the Federal Aviation Administration enough to continue flying RyanAir? Or will I have to plump for much less convenient alternatives?

Hmmm…

Merry Xmas

70 is NOT “the new 50”

What’s weird about a relentlessly ageing society is its equally relentless determination to avoid talking about the realities of ageing and death. Suddenly it’s ‘ageist’ to refer to somebody as “old”. They’re just “older” — which is idiotic, when you think about it: everybody is, by definition, older than somebody else. And as for the slogan that “70 is the new 50″… (Which, as an interesting NYT piece puts it, is “a rosy falsehood contradicted by any serious study of the age curve for major diseases”. For people older than 85, for example, the risk of developing Alzheimer’s is 14 times higher than for those ages 65 to 69.)

And, as the piece points out, the current decline in birth rates in countries like the US means that

there will be many fewer young and middle-aged people to care for the frailest of the old, whose death rate has not increased in recent years. The population of the prime caregiving age group, from 45 to 64, is expected to increase by only 1 percent before 2030, while the population over 80 will increase by 79 percent.

Our inability to think about — let alone plan for — the future is obviously a cultural thing (and is different in non-Western societies). But I wonder how much of it is also a by-product of the way Western democracies are now driven by five-year electoral cycles. No politician nowadays seems capable of long-term thinking.

And then there is the strange fact that five of the candidates for President — Joe Biden, Michael Bloomberg, Bernie Sanders, Donald Trump and Elizabeth Warren — are septuagenarians.

[Full disclosure: this blogger is over 70 and can testify that it is not the new 50! Nor is he running for president of anything.]

Trump writes, and this is what he wrote

This is his signature on the screwball letter he wrote to Speaker Pelosi.

A blogger’s mascot

Building vs. Streaming

Every Saturday morning for as long as I can remember, BBC Radio 3 has had a programme at 9am called “Building a Library”, in which a group of experts review recordings of classical music with a view to recommending the one(s) that the listener should contemplate adding to his or her ‘library’. The implicit model is that the music comes on a disc, which made complete sense in the pre-streaming era. The fact that the channel is still running the programme suggests that lovers of classical music still buy discs, which I guess really marks them out nowadays from lovers of pop, rap, etc., most of whom probably get their music from streaming sources. In which case a ‘library’ is now a playlist, I guess.

Fancy a job in Bletchley Park?

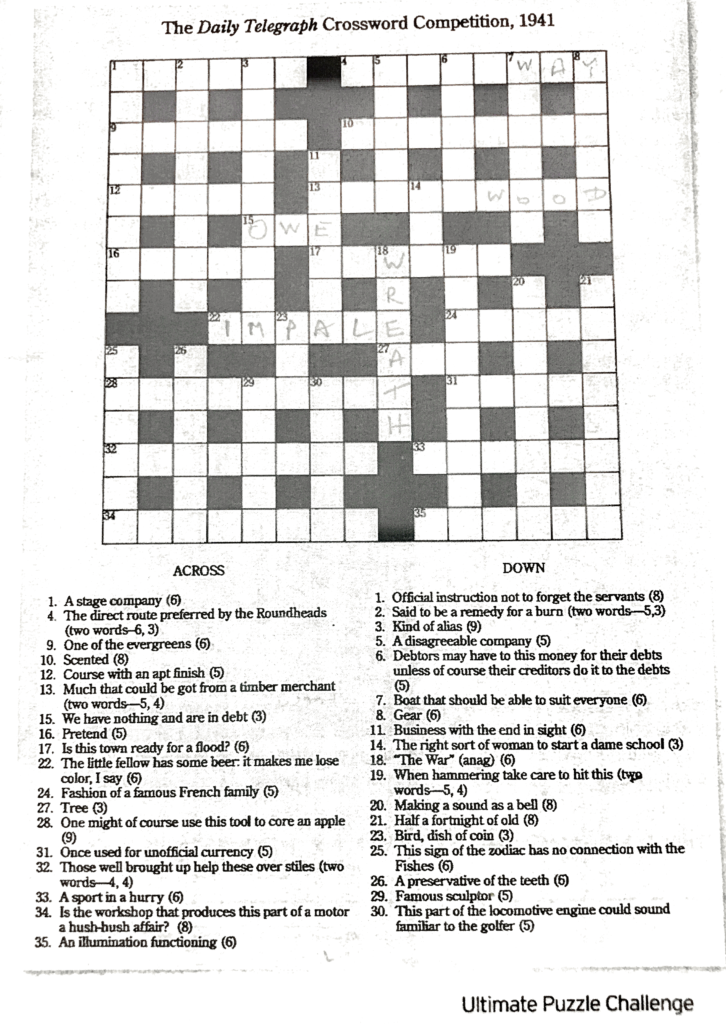

In late 1941, a mysterious Mr Gavin wrote to the Daily Telegraph offering £100 to be donated to charity if anyone could solve this crossword in less than 12 minutes. The competition was to be held at the Telegraph’s office in Fleet Street, London.

A few weeks later those who managed it received letters asking them to report to Military Intelligence (that well-known oxymoron), which then sent them on to Bletchley Park.

This recruitment method would never get past HR nowadays. But then, there was a war on.

(As you can see, someone in our house has been having a go at it!)

It’s different from the cryptic puzzles one finds nowadays in the posher newspapers — it’s a mixture of cryptic and quick clues.