Emma Freud told an interesting story on the radio this morning about her father, Clement. He had, she said, “a perfect death”. On the day in question, he’d been to the races (at Exeter), had won on the horses, had a good lunch with his “second best friend” (apparently he was punctilious about ranking his friendships), and was writing his column (about the Exeter meeting) for a racing newspaper when he dropped dead in mid-sentence. The next day, Emma and her Mum woke up his computer and found that the last words he’d written were “In God’s good time…”.

Category Archives: Asides

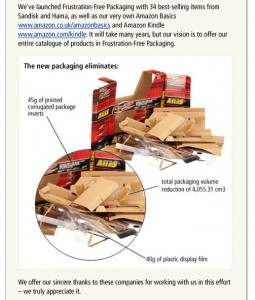

An end to wrap-rage?

Ever bought an SD or Compact Flash card and entertained fantasies about using the scissors which has just nearly sliced your thumb off to slit the throat of the guy who designed the packaging? Join the club. But help may be at hand. When I logged into Amazon.co.uk this morning, I found this:

It seems they’re doing deals with suppliers to create “frustration-free packaging”. About time too.

Prejudices from an exhibition

Anthony Lane has a lovely piece in the New Yorker about the new exhibition of Robert Frank’s famous visual study of his adopted country. Here’s how it begins:

In June, 1955, Robert Frank bought a car. It was a Ford Business Coupe, five years old, sold by Ben Schultz, of New York. From there, Frank drove by himself to Detroit, where he visited the Ford River Rouge plant, in Dearborn, as if taking the coupe home to see its family. Later that summer, he headed south to Savannah, and, with the coming of fall, set off from Miami Beach to St. Petersburg, and then struck out on a long, diversionary loop to New Orleans, and thence to Houston, for a rendezvous with his wife, Mary, and their two children, Pablo and Andrea. Together, they went west, arriving in Los Angeles in the nick of Christmastime. They stayed on the Pacific Coast until May of the following year, when Mary and the children returned to New York. Frank, however, still wasn’t done. Alone again, he made the trip back, going via Reno and Salt Lake City, then pushing north on U.S. 91 to Butte, Montana. From there, it was a deep curve, though a swift one, through Wyoming, Nebraska, and Iowa to Chicago, where he turned south; at last, by early June, Frank and his Ford Business, his partner for ten thousand miles, were back in New York. It had been a year, more or less, since he embarked, and there was much to reflect upon. Luckily, he’d taken a few photographs along the way.

In fact, he took around twenty-seven thousand…

In the end, Frank chose only 83 images from the 27,000 for the book which was published in November 1958 in Paris under the title Les Americains. From all of this he earned the princely sum of $817. He also received a lot of ordure from American critics, who were infuriated by his calm, detached view of their variegated, segregated, free-enterprise paradise. They saw this Swiss immigrant photographer as an agitator, the enemy within. (Remember, though, that this was the country which spawned Senator McCarthy.) Lane’s piece — and the contemporary exhibition — looks at The Americans with a less hysterical eye. The New Yorker prints Frank’s photograph of customers at a Drug Store counter in Detroit, a fascinating, disturbing image in which every countenance seems to tell a story. Here’s how Lane describes it:

Every stool is taken; the customers are waiting for their orders, two of them clasping their hands as if saying grace. Half of them look straight ahead, like drivers in dense traffic; not one seems to be talking to his neighbors. As Greenough [Curator of the current exhibition] suggests, this broken togetherness would have been bewildering to one who grew up amid the café society of Europe, with its binding hubbub.

Mind you, what would the diners say, if quizzed on their silence? Maybe they just came off a noisy shift, and could use a minute’s peace; maybe they’re simply tired and hungry; maybe, with a grilled-cheese sandwich and a cup of coffee inside them, they might warm up, and, if the man with the camera returned in half an hour, he would walk into a perfect storm of yakking. Whenever I see Frank’s photograph, with its citrus slices of cardboard or plastic dangling overhead, I think of “The Blues Brothers,” and John Candy briskly ordering drinks for himself and a couple of cops: “Orange whip? Orange whip? Three orange whips.” For every segment of melancholia that Frank cut from America, in other words, America could dish up a comic response, or at least an upbeat equivalent.

The great thing about the exhibition — and the massive book that’s been spun off from it, is that it enables us to look behind the editing and selection process that Frank employed when whittling down his 27,000 images to 83.

When he picked up a pair of hitchhikers and allowed one of them to drive, the sideways image that he took shows the driver—a dead-eyed ringer for Richard Dreyfuss in “Close Encounters of the Third Kind”—in determined profile. Check the contact sheet at the back of the catalogue, and you come across the succeeding frame: same angle, same guy, but now with a definite grin—closer in mood, instantly, to the Dreyfuss who gunned his truck in pursuit of the alien craft, his face lit with chirpy wonder.

The extra information one gleans from seeing contact sheets and Frank’s notes should caution anyone from drawing bold inferences from any single image, because often such interpretations involve projecting one’s own prejudices onto the photograph. A famous photograph in The Americans shows a number of smartly-dressed black dudes lounging alongside cars at a funeral. It was taken in North Carolina, I think, and many viewers over the years (me included) assumed that the men were probably chauffeurs patiently waiting for their white masters. But Frank’s contact sheet reveals that the men are actually attending an African-American funeral.

This is an exhibition I’d love to see, but it doesn’t seem to be coming to Europe. Ah well, I’ll just have to get the book

En passant: The New Yorker has a small slideshow to accompany Anthony Lane’s piece.

Meditation on a computer game

Lovely piece in the London Review of Books by Thomas Jones. Sample:

It’s 17 years since I stopped writing computer games: a combination of my going to a new school, the onset of adolescence and the BBC Micro becoming obsolete. There are still a few functioning Beebs around the place: a number of Britain’s railway stations apparently still use them to run their platform displays. But if, for nostalgia or any other reason, you’d like to get your hands on one, you don’t need to go to the trouble of robbing a railway station, because you can easily, free of charge, download an emulator from the internet. This is a piece of software that allows you to pretend that your PC is a BBC: the ultimate downgrade. A couple of days ago, I wrote a short BASIC program which allowed me to make a little man run about the screen. I even solved a problem that I’d completely forgotten had ever bothered me. It was a very simple problem, which had nothing to do with my understanding of BASIC and everything to do with my inability to work out the logical steps underpinning the procedure. The results were utterly unremarkable, and would have been equally unremarkable (to anyone apart from me) in the mid-1980s. But it gave me quiet satisfaction all the same: I worked out, after twenty years, how to make the little man jump.

Good news about the Republicans

Lovely NYTimes column by Frank Rich. Sample:

BARACK OBAMA’S most devilish political move since the 2008 campaign was to appoint a Republican congressman from upstate New York as secretary of the Army. This week’s election to fill that vacant seat has set off nothing less than a riotous and bloody national G.O.P. civil war. No matter what the results in that race on Tuesday, the Republicans are the sure losers. This could be a gift that keeps on giving to the Democrats through 2010, and perhaps beyond.

The governors’ races in New Jersey and Virginia were once billed as the marquee events of Election Day 2009 — a referendum on the Obama presidency and a possible Republican “comeback.” But preposterous as it sounds, the real action migrated to New York’s 23rd, a rural Congressional district abutting Canada. That this pastoral setting could become a G.O.P. killing field, attracting an all-star cast of combatants led by Sarah Palin, Glenn Beck, William Kristol and Newt Gingrich, is a premise out of a Depression-era screwball comedy. But such farces have become the norm for the conservative movement — whether the participants are dressing up in full “tea party” drag or not.

The battle for upstate New York confirms just how swiftly the right has devolved into a wacky, paranoid cult that is as eager to eat its own as it is to destroy Obama. The movement’s undisputed leaders, Palin and Beck, neither of whom has what Palin once called the “actual responsibilities” of public office, would gladly see the Republican Party die on the cross of right-wing ideological purity. Over the short term, at least, their wish could come true…

Yippee!

There must be easier ways of earning a living…

Become EU Prez, then go to gaol

Eh? George Monbiot’s supporting Blair’s candidacy for the EU Presidency? Well, here’s what he says:

Tony Blair’s bid to become president of the European Union has united the left in revulsion. His enemies argue that he divided Europe by launching an illegal war; he kept the UK out of the eurozone and the Schengen agreement; he is contemptuous of democracy (surely a qualification?); greases up to wealth and power and lets the poor go to hell; he is ruthless, mendacious, slippery and shameless. But never mind all that. I’m backing Blair….

Read on, my friends, read on. George has a Cunning Plan.

The utility of pure curiosity

Pondering the strange paradox that Cambridge is currently ranked second (after Harvard) in the world ranking of universities, despite the fact that its income is probably only a fifth of Harvard’s, I came on this terrific blog post by Mary Beard, who is Professor of Classics at Cambridge. Excerpt:

I still have a terrible sinking feeling about the new Research Excellence Framework, and its stress on the ‘impact’ of research. I took a good hard look at the recent consultation document produced by HEFCE … and at the “indicators” which might demonstrate “impact”. There are almost forty indicators, of which only four or five could possible ever apply to an arts and humanities subject. Most refer to income from industry, increased turnover for particular businesses, improved health outcome, better drugs (medicinal rather than recreational I imagine) and changes in public opinion (eg reductions in smoking). One of my colleagues ruefully observed that humanities research probably had a track record of encouraging smoking, at least among researchers… all that angst in the library.

Even the indicators which looked as if they might apply to us. Try “enriched appreciation of heritage or culture, for example as measured through surveys.” How on earth would a survey show the impact of, lets say, Wittgenstein? Even HEFCE seems to have given up at the end. Under the category “Other quality of life benefits” there were no indicators. Someone had just written “Please suggest what might be included”. A generous appeal to the academic community, or desperation?

[…]

British research punches far above its weight — unlike British sport (which is no more “useful”). If our middle distance runners did half as well as our universities (four out of the top six in the recent world ranking are British), there would be a national celebration and a triumphal procession in an open topped bus.

And look at the money the government is pouring into sport, on the correct principle … that you have to support generously a wide range of activities and people, in order to produce a very few medallists. Why dont they use that argument for academic research too?

The life of the mind

Saturday dawned damp and overcast, as if November had arrived early. The wind had begun to strip the trees, carpeting the footpath with leaves. It seemed like a day for hunkering down with the newspapers and a good book. But then I remembered that it’s Cambridge’s annual ‘Festival of Ideas’ (the Humanities’ counterpart to the Science Festival of which I’m a Patron). The philosopher Hugh Mellor was billed to give a talk on Frank Ramsey in the University Library at 11am. So I got up and went to hear him.

Frank Ramsey is a Cambridge legend — a wunderkind who died tragically young at the age of 26, and yet made an indelible impression on those who had known him.

I first heard of him when I came to Emmanuel in 1968 and bought a battered copy of Keynes’s Essays in Biography in which there’s an essay on this prodigious mathematican-cum-philosopher-cum-economist. In it, Keynes laments the passing of his young protege and remembers

“His bulky Johnsonian frame, his spontaneous gurgling laugh, the simplicity of his feelings and reactions, half-alarming sometimes and occasionally almost cruel in their directness and literalness, his honesty of mind and heart, his modesty, and the amazing, easy efficiency of the intellectual machine which ground away behind his wide temples and broad, smiling face, have been taken from us at the height of their excellence and before their harvest of work and life could be gathered in.”

Ramsey published only two papers in economics (which was not his main field). They were published in the Economic Journal (of which Keynes was the editor). The first (published in 1927) was “A Contribution to the Theory of Taxation”; the other was “A Mathematical Theory of Saving,” published in December 1928. It addressed the problem of how much should a nation save, and was, wrote Keynes,

“one of the most remarkable contributions to mathematical economics ever made, both in respect of the intrinsic importance and difficulty of its subject, the power and elegance of the technical methods employed, and the clear purity of illumination with which the writer’s mind is felt by the reader to play about its subject”.

Professor Mellor’s talk (largely based on this biographical essay) was fascinating, liberally illustrated with sound clips from a radio profile of Ramsey that he had made with the BBC many years ago (and which is available from the Cambridge Dspace archive if you’re interested). I loved this clip, in which I.A. Richards remembers an early encounter with Ramsey as a teenager:

“Well, my old friend C. K. Ogden had a very queer place called ‘Top Hole’ – named after a war cartoon – above MacFisheries in Petty Cury, and one afternoon there, a tap on the door and in came this tall, ungainly, rather gangling boy. We knew who he was instantly – he looked so like his mother – and in no time almost he was at home. He was from Winchester where he’d been for some time with no one doing much more than saying ‘The library is yours, just do what you want’. He was recognised clearly at Winchester as quite one of the wonders; and there he was, and we chatted along for some time, and then he turned to Ogden and said: ‘Do you know, I’ve been thinking I ought to learn German. How do you learn German?’. Ogden leaped up instantly, rushed to the shelf, got him a very thorough German grammar – and a dictionary, Anglo-German dictionary – and then hunted on the shelves and found a very abstruse work in German – Mach’s Analysis of Sensations – and said: ‘You’re obviously interested in this, and all you do is to read the book. Use the grammar and use the dictionary and come and tell us what you think’. Believe it or not, within ten days, Frank was back saying that Mach had misstated this and that he ought to have developed that argument more fully, it wasn’t satisfactory. He’d learned to read German – not to speak it, but to read it – in almost hardly over a week.”

Four things stand out in my memory from Professor Mellor’s talk.

“Well, he’d had a very hard time with the Tractatus, and all sorts of people were called in, and didn’t like any version they could make of it. They couldn’t make it make as good sense in English as – if it made any good sense in German – they thought it should. [G.E.] Moore had been insisting very much that it wasn’t translatable – it would be much better left just as it was. After inventing a title – Moore’s title – one way and another it got into a kind of discard; and then I don’t know who suggested that Frank ought to have a try at it, and as soon as Frank and Wittgenstein got together over this it was clear that there was a possibility.”

The Tractatus impressed Ramsey enormously. He, like everyone else, found it exceedingly difficult, and he took immense trouble to try and understand it. In the autumn of 1923, after graduating from Trinity College as a Wrangler – i.e. with a First in Part II of the Mathematics Tripos – he went to Austria to visit Wittgenstein, who was then living in a small village outside Vienna. In a letter home, Ramsey gave a vivid picture of Wittgenstein’s life and of the intensity of their conversations.

“Wittgenstein is a teacher in the village school. He is very poor, at least he lives very economically. He has one tiny room, whitewashed, containing a bed, washstand, small table and one hard chair and that is all there is room for. His evening meal which I shared last night is rather unpleasant coarse bread, butter and cocoa. His school hours are eight to twelve or one and he seems to be free all the afternoon. He is prepared to give four or five hours a day to explaining his book. I have had two days and got through seven out of eighty pages. He has already answered my chief difficulty which I have puzzled over for a year and given up in despair myself and decided he had not seen. It’s terrible when he says ‘Is that clear?’ and I say ‘No’ and he says ‘Damn, it’s horrid to go through all that again’.”

Thirdly, I hadn’t known is that Ramsey had done pioneering work in the philosophy of science, in particular on the nature of theories. His view was that any scientific theory has to be reducible to a single (perhaps very long) sentence. The Cambridge philosopher Richard Braithwaite described it thus:

“Ramsey produced therefore a very interesting view of how to consider these theoretical concepts. … it wasn’t the case that the sentences about electrons and protons and so on were to be translated directly into propositions about observables. These terms played their part in extremely complex sentences – in a form which were twenty years later called Ramsey sentences – which had both them and observables in as well. So that a treatise of physics would really be one big long sentence – it would be rather like a fairy story starting ‘Once upon a time there was a man who …’ or ‘Once upon a time there was a frog which …’, the rest of the story going on to describe the adventures of the man or the adventures of the frog. A treatise on electrons, in Ramsey’s view, starts by saying ‘There are things which we will call electrons which …’, and then goes on with the story about the electrons … only of course you then believe the whole thing, the whole ‘There is …’ sentence, whereas in a fairy story of course you don’t.”

What’s really interesting, though, is what Ramsey was able to infer from this view of theories. He contended that “no single bit of a scientific theory can be understood apart from that theory; and bits of rival theories can’t be dismissed just because they don’t occur in our theory”. Thus, “The adherents of two such theories could quite well dispute, although neither affirmed anything the other denied”. This insight, which is essentially a description of the way in which rival scientific paradigms can be ‘incommensurable’, lay buried for decades, until it surfaced in 1962 as a key idea in Thomas Kuhn’s book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Kuhn’s picture of science as a process of ‘normal science’ conducted around an agreed theoretical paradigm punctuated by occasional ‘revolutions’ in which one paradigm is overthrown by a newer one contained a shocking conjecture: because rival paradigms are ‘incommensurable’ — i.e. there exists no neutral language or conceptual structure in which the merits of the rivals can objectively be assessed — then essentially progress in science depends on non-rational factors. Or, to put it crudely, scientific progress depends on occasional bouts of what one critic called “mob psychology”. This offended many people — notably Karl Popper — but I don’t think anyone has really refuted it. The intriguing thing for me was the discovery that essentially the idea goes back to Frank Ramsey in 1920s Cambridge.

Finally, I discovered that Ramsey’s wife was Lettice Ramsey — the ‘Ramsey’ in Ramsey & Muspratt, the photographic studio in Post Office Terrace which photographed most Cambridge and Oxford academics for the best part of a century and which was demolished to make way for the Grand Arcade shopping mall. The firm’s archive has, it seems, gone to the Cambridgeshire Collection in the City library.

I’m on my way.

Behavioural therapy

Neat, eh?