We went to lunch at one of our favourite restaurants the other day and, before ordering, were given the standard board with bread plus butter and Balsamic vinegar in olive oil. This led us to wonder if the management knew we were slaves of OS X. Purists will argue that it must be coincidence — it lacks the mandatory bite out of the right-hand-side of the image. Still…

Category Archives: Asides

What the Google spat reveals about China

James Fallows — who recently returned to the US after a stint in China, whence he used to send very perceptive dispatches — has an interesting perspective in The Atlantic about the Google decision.

He thinks it represents a significant moment — “Significant for Google; and while only marginally significant for developments inside China potentially very significant for China’s relations with the rest of the world.”

In terms of its impact on Chinese Internet users, Fallows thinks that it’s not such a big deal.

In terms of information flow into China, this decision probably makes no real difference at all. Why? Anybody inside China who really wants to get to Google.com — or BBC or whatever site may be blocked for the moment — can still do so easily, by using a proxy server or buying (for under $1 per week) a VPN service. Details here. For the vast majority of Chinese users, it’s not worth going to that cost or bother, since so much material is still available in Chinese from authorized sites. That has been the genius, so far, of the Chinese “Great Firewall” censorship system: it allows easy loopholes for anyone who might get really upset, but it effectively keeps most Chinese Internet users away from unauthorized material.

The real significance, he argues, is that it may signify that China is entering its own “Bush-Cheney era”.

There are also reasons to think that a difficult and unpleasant stage of China-U.S. and China-world relations lies ahead. This is so on the economic front, as warned about here nearly a year ago with later evidence here. It may prove to be so on the environmental front — that is what the argument over China’s role in Copenhagen is about. It is increasingly so on the political-liberties front, as witness Vaclav Havel’s denunciation of the recent 11-year prison sentence for the man who is in many ways his Chinese counterpart, Liu Xiaobo. And if a major U.S. company — indeed, Google has been ranked the #1 brand in the world — has concluded that, in effect, it must break diplomatic relations with China because its policies are too repressive and intrusive to make peace with, that is a significant judgment.

[…]

In a strange and striking way there is an inversion of recent Chinese and U.S. roles. In the switch from George W. Bush to Barack Obama, the U.S. went from a president much of the world saw as deliberately antagonizing them to a president whose Nobel Prize reflected (perhaps desperate) gratitude at his efforts at conciliation. China, by contrast, seems to be entering its Bush-Cheney era. For Chinese readers, let me emphasize again my argument that China is not a “threat” and that its development is good news for mankind. But its government is on a path at the moment that courts resistance around the world. To me, that is what Google’s decision signifies.

This echoes something that Mark Anderson has been saying for ages — now reprinted on his blog:

Too often, today, sloppy thinkers and Western optimists assume that China is just a Big America, or a Big Vietnam, or a Fast India – or their Next Big Business Partner.

Wrong. At a time when the world thinks the communist model has been proved obsolete, China remains a communist country. In fact, under the current leader, Hu Jintao, human rights in China have recently suffered and are now in serious decline, according to Amnesty International-USA, the Committee to Protect Journalists, Human Rights Watch, and others.

China has tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of human censors monitoring citizen clicks and comments on the China government–controlled Internet. When my friend’s teenage daughter (a U.S. citizen) taught English there last year, police came to her apartment and grilled her about specific computer entries she had made. When one of Australia’s top mining firms, Rio Tinto, refused to allow China’s Chinalco to double its ownership interest last year (to 18%), China arrested local CEO (and Australian citizen) Stern Hu and three managers, who remain in jail today, under espionage charges. China denies any connection. In politics, thought, and business, China remains a police state.

We all refer to China as “China” now, as though it’s just One of the Gang, like “Ohio” or “Denmark”; after all, it’s a member of the G7, right? Just another market economy finding its way in the global river of events —

No, it’s not. And it isn’t in the G7. In fact, it isn’t even part of the G8, which includes Russia.

So now ask yourself: When is the last time you called Communist China, Communist China?

You’d better get used to it. There is no indication that the Chinese Communist Party has any intention of giving up any power at all, or of changing its power structure. In fact, discussion of anything political is basically off limits inside China; it is not done. Ah, you heard that there were some small moves toward shadow property rights in China? Sorry, that move has recently been reversed.

Mark goes on to itemise what he sees as the main tenets of Chinese policy. In his (bleak) view, they are:

1. Steal Intellectual Property.

2. Use Slave Labor Rates to Become the Low-Cost Producer of All Goods and Services.

3. Sell Stolen IP Back As Global Exports.

4. Industrial Policy: Subsidize Key Industries.

5. Prevent (or Restrict) Unwanted Imports.

6. Use Currency Manipulation to provide artificial aid to your export companies.

7. Price for Export, Suppress Domestic Consumption, and use domestic savings to drive the above policies.

8. Create the Appearance of Free and Fair Trade, Without the Fact.

9. Encourage Foreign Direct Investment – But Don’t Allow Controlling Ownership.

These are just the headlines — you need to read the full post to get the detail.

Google, China and staying on message

Just before 6pm yesterday I had a phone call from the Comment Desk of the (London) Times. Would I be interested in writing an OpEd piece about the Google business and how it shows that attempts to censor the Internet are doomed? I replied that I wished that were true, but that, sadly, it isn’t, and that the moral of the Google furore is that determined governments can effectively censor the Net. I’d be happy to write a piece explaining this, I said. “Oh”, replied my caller, “that’s very interesting. I need to go back to my editor to discuss it. I’ll phone back later.”

Needless to say, he didn’t. But this morning the paper ran a rather good piece by George Walden arguing that Google was right to do the original deal, and is right to threaten to quit now, and expressing the hope that the Chinese will reach an accommodation with the company. Somehow, that seems like a faint hope. And if the Chinese do decide to talk to Google, then we will know that something has really changed in the Middle Kingdom.

LATER: Just to underscore the point I was trying to make to the Times guy, the New York Times this morning reports that:

Google’s declaration that it would stop cooperating with Chinese Internet censorship and consider shutting down its operations in China ricocheted around the world on Wednesday. But in China itself, the news was heavily censored.

Some big Chinese news portals initially carried a short dispatch on Google’s announcement, but that account soon tumbled from the headlines, and later reports omitted Google’s references to “free speech” and “surveillance.”

The only government response came later in the day from Xinhua, the official news agency, which ran a brief item quoting an anonymous official who was “seeking more information on Google’s statement that it could quit China.”

The decade with no name

The New Yorker has a lovely essay by Rebecca Mead about the decade that ended last night. In almost every way one looks at it, the ‘noughties’ look like a wasted decade.

The events of and reaction to September 11th seem to be the decade’s defining catastrophe, although it could be argued that it was in the voting booths of Florida, with their flawed and faulty machines, that the crucial historical turn took place. (In the alternate decade of fantasy, President Gore, forever slim and with hairline intact, not only reads those intelligence memos in the summer of 2001 but acts upon them; he also ratifies the Kyoto Protocol and invents something even better than the Internet.) And if September 11th marked the beginning of this unnameable decade, its end was signalled by President Obama’s Nobel acceptance speech, in which he spoke of what he called the “difficult questions about the relationship between war and peace, and our effort to replace one with the other,” and painstakingly outlined the absence of any good answers to the questions in question.

In between those two poles, the decade saw the unimaginable unfolding: the depravities of Abu Ghraib, and, even more shocking, their apparent lack of impact on voters in the 2004 Presidential election; the horrors of Hurricane Katrina and the flight of twenty-five thousand of the country’s poorest people to the only slightly less hostile environs of the Superdome; the grotesque inflation and catastrophic popping of a housing bubble, exposing an economy built not even on sand but on fairy dust; the astonishing near-collapse of the world financial system, and the discovery that the assumed ironclad laws of the marketplace were only about as reliable as superstition. And, after all this, the still more remarkable: the election of a certified intellectual as President, not to mention an African-American one.

Chelsea-on-Sea

To Burnham Market, the poshest small town in England, for lunch. It’s still the lovely place I remember from when we used to go there two decades ago, but has gone spectacularly up-market — to the point where it now resembles nothing so much as Chelsea-on-Sea. Streets choc-a-bloc with Porsche Cayman and Toucan Touareg SUVs, boutiques selling trinkets that cost more than the Gross National Product of Ecuador, cheery gels with names like Camilla and Eugenie and Amanda wearing green wellies — you can imagine the scene. But still, unaccountably, charming. I was reminded of the time, years ago, when a good friend of mine dreamed of buying a little house in Burnham Market and settling down to a career writing scandalous novels. (She never managed it, and became an academic instead. But today I imagined her casting an ironic eye on the visiting Yuppies, and using them as characters in a comic novel.)

Our plan was to lunch in the Hoste Arms, but given that (a) we arrived at 1pm, (b) it was wet and cold (and (c) the middle of the holiday season to boot) we should have known better: it was heaving with lunchers. So we found a small cafe and had lovely pea soup and sandwiches instead.

Our plan was to lunch in the Hoste Arms, but given that (a) we arrived at 1pm, (b) it was wet and cold (and (c) the middle of the holiday season to boot) we should have known better: it was heaving with lunchers. So we found a small cafe and had lovely pea soup and sandwiches instead.

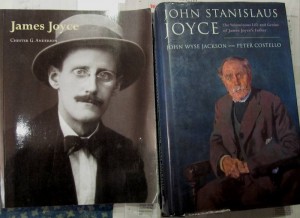

And then we stumbled on the loveliest little secondhand bookshop which had the best collection of biographies I’ve seen in a while — including Chester Anderson’s short illustrated biography of Joyce and the fascinating biography that John Wyse Jackson and Peter Costello wrote of John Joyce, James’s reprobate of a father. I walked out clutching both, and only £11 poorer. Bliss.

Into the wind

We reached Cley yesterday afternoon just as the light was running out. It was a grey, overcast day when all of Norfolk seemed to have gone brown (though if you looked carefully at the hedgerows that turned out not to be true: there were red berries everywhere). As we turned towards the beach a huge flock of birds suddenly started into the air, turning and twisting and making those astonishing fleeting patterns that lead mathematicians to work out flocking algorithms. And they headed seawards and were gone from sight, almost as quickly as they had appeared. We parked under the shingle bank, now much reduced since its glory days, and prepared to get out for what we imagined would be a brisk walk. But then I opened the car door the wind promptly forced it shut again, so it was clear that something more than a brisk constitutional was on offer. Something that required firm resolve — and serious outerwear. So we opened the boot and, in the shelter of the lid, dressed as for the South Pole.

When we got to the top of the bank, the full force of the wind hit us. There was an angry brown sea, with a heavy swell and sizeable waves pounding against the shore. Interestingly, they were coming in at an angle of about fifteen degrees to the line of the beach, so suddenly one saw how this coastline is constantly being reshaped.

We turned into the wind and began to walk. It was eye-wateringly cold, with the wind scything through anything (like trousers and hats) that wasn’t comprehensively windproof. And yet the strange thing was that the beach was dotted with tiny, pyramidical structures which, on closer inspection, turned out to be tented bivouacs, each one containing a fisherman who sat there, staring intently at a massive fishing rod, resting on a tripod support, and each at the end of a line which had been cast far out into the raging surf. It was absolutely surreal, and made one wonder what it is that induces people to undergo such discomfort in pursuit of private obsessions. And then to marvel at it, for it is what makes us humans so interestingly perverse.

But much as I admired the fishermen’s fortitude, mine wilted in the teeth of the gale, and we turned back and sought the shelter of the car and, later, the blazing fire of an hotel. Ernest Shackleton would not have been impressed.

The Noughties: the Big Zero

Nice NYT column by Paul Krugman looking back on a wasted decade.

From an economic point of view, I’d suggest that we call the decade past the Big Zero. It was a decade in which nothing good happened, and none of the optimistic things we were supposed to believe turned out to be true.

It was a decade with basically zero job creation. O.K., the headline employment number for December 2009 will be slightly higher than that for December 1999, but only slightly. And private-sector employment has actually declined — the first decade on record in which that happened.

It was a decade with zero economic gains for the typical family. Actually, even at the height of the alleged “Bush boom,” in 2007, median household income adjusted for inflation was lower than it had been in 1999. And you know what happened next.

It was a decade of zero gains for homeowners, even if they bought early: right now housing prices, adjusted for inflation, are roughly back to where they were at the beginning of the decade. And for those who bought in the decade’s middle years — when all the serious people ridiculed warnings that housing prices made no sense, that we were in the middle of a gigantic bubble — well, I feel your pain. Almost a quarter of all mortgages in America, and 45 percent of mortgages in Florida, are underwater, with owners owing more than their houses are worth.

Last and least for most Americans — but a big deal for retirement accounts, not to mention the talking heads on financial TV — it was a decade of zero gains for stocks, even without taking inflation into account. Remember the excitement when the Dow first topped 10,000, and best-selling books like “Dow 36,000” predicted that the good times would just keep rolling? Well, that was back in 1999. Last week the market closed at 10,520.

So there was a whole lot of nothing going on in measures of economic progress or success. Funny how that happened.

Davewatch

During the recent snowy spell, we took to putting newspaper down in the hall to reduce the amount of snow brought into the house. As luck would have it, the Guardian G2 issue about Dave Cameron was the first periodical that came to hand. We noticed that people stamped their Wellingtons rather enthusiastically upon entering. But at least they were green. Poor Dave became progressively more disfigured over the week, so in the end we put him out of his misery. On the fire.

Surreal estate

Tiger Woods’s unbelievably naff other place in Florida. Described by one observer as “a cross between a discount motel and a beachside nursing home”.

Tiger’s crash: the Top Gear angle

Phil Greenspun has decided not to order the Cadillac Escalade after all.

Imagine a group of engineers so gifted that U.S. taxpayers were willing to spend more than $50 billion to keep them together. These folks designed a vehicle that weighs 6000 lbs. empty and is advertised as having safety advantages over cars designed by companies that operate without continuous government assistance. Tiger Woods, a man whose physique is presumably far more durable than average, drives this vehicle across a lawn and into a tree at a pretty low speed. Did he bound out of his Cadillac Escalade without a scratch? According to the New York Times, “Woods was slipping in and out of consciousness. [the police] said Woods suffered lacerations to his upper and lower lips and blood in his mouth, and that he was treated on scene for 10 minutes before being transported to a nearby hospital.”

Yep. I’ve cancelled my order too.