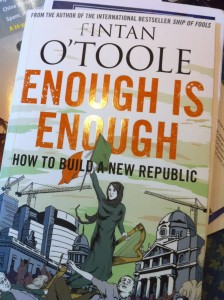

I’ve been reading Fintan O’Toole’s new book about the Irish banking catastrophe. As in his previous book — Ship of Fools: How Stupidity and Corruption Sank the Celtic Tiger

— the analysis of why the disaster happened is spot-on: the Republic has had a dysfunctional political culture ever since it was founded, and the dysfunctionality became pathological over the last three decades. O’Toole thinks that the only way of ensuring a decent future for the country is radically to re-think the governance of the state, and he’s right.

For example, the system of proportional representation based on multi-member constituencies has been good at ensuring parliamentary representation that is proportional to the level of public support, but terrible at delivering good governance, because it favours sectionalism, clientilism, cronyism and parish-pump politics to the detriment of overarching national concerns. Most Irish TDs (i.e. MPs) spend most of their time attending to the detailed needs of constituents: if a haulier wants a contract from a local authority, for example, his first step will be to contact his TD who will in turn contact the authority in question; a developer who wants planning permission to build on the foreshore (which is forbidden by planning regulations) will write to his TD, who will then… You get the picture. Yet these are also the guys who, as ministers, are expected to regulate banks, negotiate treaties and generally run a modern state.

I remember a salutary example of how attentive Irish TDs are to their constituents. My father was a totally non-political person who never had anything to do with politicians. But one of the TDs in the (multi-member) constituency in which we lived happened to be also the Taoiseach (Prime Minister) at the time. Da died of a heart attack around 7am in the local hospital. At 7.30am a telegram from the Taoiseach arrived at the family home expressing his sincere condolences at our sad loss. Someone in the hospital had phoned the local Fianna Fail office and relayed the news of a constituent’s death. And that’s the way everything worked.

Ireland desperately needs better governance. It needs to re-invent itself as a truly modern Republic. The chances of it doing so, however, are close to zero. And yet, pardoxically, this is the time to do it. As the Obama crowd used to say: never waste a good crisis. The moment when people have been shocked into confronting reality is the best time to get them to take serious ideas seriously.

In his column in today’s Irish Times, O’Toole makes some really good points. “In their quiet, dark moments”, he writes, “Cowen [Taoiseach] and Lenihan [Finance Minister] must have been haunted

by the ghost of their political progenitor, Éamon de Valera. Dev’s moment of greatest national popularity came in May 1945, at the end of the war in Europe, when he delivered his magisterial reply to Winston Churchill’s bitter attack on Irish neutrality.

Remaining neutral may not have been the most noble of causes, but it was the ultimate declaration of Irish sovereignty. At a time when three great powers – Germany, Britain and the US – contemplated an invasion of Ireland, de Valera managed to maintain the idea that the State would make its own decisions. The quiet gravity of his broadcast embodied for Irish people of different allegiances what sovereignty is ultimately about: dignity.

This sent me hunting for the text of Dev’s radio broadcast, which makes an interesting read in today’s circumstances. de Valera was responding to a taunt in Winston Churchill’s VE-day speech about Ireland’s decision to assert its sovereignty by remaining neutral in the Second World War, and by denying Britain the use of the so-called ‘Treaty’ ports which Churchill (and the Allies) thought would be essentially to combat the U-Boat threat in the North Atlantic. “It is indeed fortunate”, said Dev,

that Britain’s necessity did not reach the point when Mr. Churchill would have [invaded Ireland]. All credit to him that he successfully resisted the temptation which, I have not doubt, may times assailed him in his difficulties and to which I freely admit many leaders might have easily succumbed. It is indeed hard for the strong to be just to the weak, but acting justly always has its rewards.

By resisting his temptation in this instance, Mr. Churchill, instead of adding another horrid chapter to the already bloodstained record of the relations between England and this country, has advanced the cause of international morality an important step-one of the most important, indeed, that can be taken on the road to the establishment of any sure basis for peace. . .

Mr. Churchill is proud of Britain’s stand alone, after France had fallen and before America entered the War.

Could he not find in his heart the generosity to acknowledge that there is a small nation that stood alone not for one year or two, but for several hundred years against aggression; that endured spoliations, famines, massacres in endless succession; that was clubbed many times into insensibility, but that each time on returning consciousness took up the fight anew; a small nation that could never be got to accept defeat and has never surrendered her soul?

Mr. Churchill is justly proud of his nation’s perseverance against heavy odds. But we in this island are still prouder of our people’s perseverance for freedom through all the centuries. We, of our time, have played our part in the perseverance, and we have pledged our selves to the dead generations who have preserved intact for us this glorious heritage, that we, too, will strive to be faithful to the end, and pass on this tradition unblemished.

Why do these words resonate today, so many decades after they were uttered? Simply because Brian Cowen leads the party that Dev founded. It probably explains the incomprehensible state of denial Cowen and Co have been in from the onset of the current crisis — to the point where it was left to an official — the Governor of the Bank of Ireland — to tell the truth about what was happening, in the process flatly contradicting his own Prime Minister. The current Fianna Fail leaders have surrendered the sovereignty that Dev prized so highly. So somewhere, deep down in even their bovine sensibilities, there must lurk a visceral sense of shame and failure.

“Ireland”, writes O’Toole,

is being placed under adult supervision. And that cuts right through to the most tender nerve of a former colony. What colonial overlords tell their subject peoples is: “You’re not fit to govern yourselves.”

That taunt is deeply embedded in our historical consciousness. Much of modern Irish history has been shaped by the attempt to disprove it. The Proclamation of Easter 1916 declares “the right of the people of Ireland to the ownership of Ireland, and to the unfettered control of Irish destinies, to be sovereign and indefeasible”. The struggle to assert this idea of popular sovereignty goes back at least to the United Irishmen of the late 18th century. Their revolutionary idea of the “sovereignty of the people” is the cornerstone of modern Irish nationalism.

And then, of course, there is the small matter of our relationship with our former colonial masters. During the roaring years of the Celtic Tiger, a new, unprecedented respectfulness on the part of the Brits entered the picture. O’Toole remembers George Osborne, then Shadow Chancellor,

writing humbly in the London Times about the Irish as the model for Britain: “They have much to teach us, if only we are willing to learn.” Osborne’s reasoning was daft, but for many Irish people there was still an extraordinary resonance to the idea of a Tory Old Etonian* with aspirations to lead Britain adopting such a humble approach to a former province of the empire. It was further proof that Ireland had definitively left behind its long history of failure and inferiority. There were no more forelocks to be tugged.

And now? Osborne is Chancellor who, at the meeting of EU finance ministers in Brussels, spoke in

the emollient, gently patronising tones of a disappointed but supportive parent: “Britain stands ready to support Ireland to bring stability.” We probably should be grateful for such support, and Osborne was obviously trying to be helpful. But it is hard not to cringe at tabloid headlines like “Britain ready to bail out Ireland with £7 billion”.

That’s a bit over the top. Osborne isn’t entirely the “disappointed but supportive parent”.** He’s realised, as the Financial Times pointed out yesterday, that the implosion of the Irish banks would have really serious implications not only for the Eurozone, but also for British banks.

Footnotes:

* Osborne is not an old-Etonian. He went to St Paul’s — which is presumeably why Boris Johnson & Co used to call him “Oik”.

** Here’s the really funny bit. Osborne has an Irish Ascendancy (i.e. protestants-on-horses) background. He is the heir to the Osborne baronetcy (of Ballentaylor, in County Tipperary, and Ballylemon, in County Waterford). Arise Sir George!