The current row over the latest WikiLeaks trove of classified US diplomatic cables has four sobering implications.

1. The first is that it represents the first really serious confrontation between the established order and the culture of the Net. As the story of the official backlash unfolds – first as DDOS attacks on ISPs hosting WikiLeaks and later as outfits like Amazon and PayPal (i.e. eBay) suddenly “discover” that their Terms of Service preclude them from offering services to WikiLeaks — the contours of the old order are emerging from the rosy mist in which they have operated to date. This is vicious, co-ordinated and potentially comprehensive, and it contains hard lessons for everyone who cares about democracy and about the future of the Net.

As I read the latest news this morning about the increasingly determined attempts to muzzle WikiLeaks, my mind was cast back to a conversation I had in the Autumn of 2000 on an island in the Puget Sound. I was attending a symposium about the political economy of the Internet, and at one stage a colleague and I took a break and sat outside on the deck smoking the politically-incorrect cigars to which he and I were partial.

My friend is one of the wisest people I know. He had a varied career, starting as an army officer and ending up as an internationally renowned scholar in the field of International Relations.

“Do you think”, he asked, “that this new technology is as revolutionary a threat to the established order as these people [at this point he gestured towards the room where the symposium discussion was raging] think?”.

“Yes I do”, I replied confidently, because I was in thrall to technological utopianism: like John Perry Barlow, I genuinely believed that the Net was beyond the reach of the established order.

My colleague said nothing but merely puffed on his cigar and gazed out to sea, where an enormous yacht, the property no doubt of a Microsoft billionaire, had anchored. Eventually I said: “What do you think?”. He puffed some more on his cigar, then looked round at me and said, simply: “We’ll see, dear boy. We’ll see.”

At that point my confident Utopianism began to evaporate. And it’s been evaporating ever since.

2. Like most people, I’ve only read a fraction of what’s been published by WikiLeaks, but one thing that might explain the official hysteria about the revelations is the way they comprehensively expose the way political elites in Western democracies have been lying to their electorates. The leaks make it abundantly clear not just that the US-Anglo-European adventure in Afghanistan is doomed (because even the dogs in the street know that, as we say in Ireland), but more importantly that the US and UK governments privately admit that too.

The problem is that they cannot face their electorates — who also happen to be the taxpayers who are funding this folly — and tell them this. The leaked dispatches from the US Ambassador to Afghanistan provide vivid confirmation that the Kharzai regime is as corrupt and incompetent as the South Vietnamese regime in Saigon was when the US was propping it up in the 1970s. And they also make it clear that the US is every bit as much a captive of that regime as it was in Vietnam. (For a vivid account of that see the essay on Vietnam in Barbara Tuchman’s March of Folly: From Troy to Vietnam).

The WikiLeaks revelations expose the extent to which the US and its allies see no real prospect of turning Afghanistan into a viable state, let alone a functioning democracy. They show that there is no light at the end of this tunnel. But the political establishments in Washington, London and Brussels cannot bring themselves to admit this. Afghanistan is, in that sense, the same kind of quagmire as Vietnam was. The only differences are that the war is now being fought by non-conscripted troops and we are not carpet-bombing civilians, but otherwise little has changed.

These realities are, of course, plain to see, because even the mainstream media, despite its need always to pay tribute to “our brave troops”, has had to report some of it. But what nobody has known until now — outside of the magic circles of the Beltway, Whitehall and NATO HQ — is that our rulers privately concede the hopelessness of the venture. The implicit cynicism and hypocrisy of this is breathtaking — and it goes a long way towards explaining the irrational fury of our political elites at having it exposed in so brutal and unmediated a fashion.

3. Thirdly, the attack of WikiLeaks ought to be a wake-up call for anyone who has rosy fantasies about whose side cloud computing providers are on. The Terms and Conditions under which they provide both ‘free’ and paid-for services will always give them with grounds for dropping your content if they deem it in their interests to do so. Put not your faith in cloud computing: it will one day rain on your parade.

4. What WikiLeaks is exposing is the way our democratic system has been hollowed out. Governments and Western political elites have been shown to be incompetent (New Labour and Bush Jnr in not regulating the financial sector; all governments in the area of climate change), corrupt (Fianna Fail in Ireland, Berlusconi in Italy; all governments in relation to the arms trade) or recklessly militaristic (Bush Jnr and Tony Blair in Iraq) and yet nowhere have they been called to account in any effective way. Instead they have obfuscated, lied or blustered their way through. And when, finally, the veil of secrecy is lifted in a really effective way, their reaction is to try to silence the messenger — as Noam Chomsky pointed out. In that sense, Simon Jenkins got it exactly right in his Guardian column yesterday:

I have no illusions about the press. I have watched enough dirt swilling down the journalistic sewer to abandon any quest therein for responsibility, accuracy, sensitivity or humility. The great American editor Oz Elliott once lectured graduates at the Columbia School of Journalism on their sacred duty to democracy as the unofficial legislators of mankind. He asked me what I thought of it. I said it was no good to me: I was trained as a reptile lurking in the gutter whose sole job was to “get the bloody story”.

Yet journalism’s stock-in-trade is disclosure. As we have seen this week with WikiLeaks, power loathes truth revealed. Disclosure is messy and tests moral and legal boundaries. It is often irresponsible and usually embarrassing. But it is all that is left when regulation does nothing, politicians are cowed, lawyers fall silent and audit is polluted. Accountability can only default to disclosure. As Jefferson remarked, the press is the last best hope when democratic oversight fails, as it does in the case of most international bodies.

Jenkins was attacked this week in the British press for his defence of WikiLeaks, on the ground that thieves should not revel in their crime by demanding that victims be more careful with their property. “But in matters of public policy”, he replied, “who is thieving what from whom? The WikiLeaks material was left by a public body, the US state department, like a wallet open on a park bench, except that in this case the wallet was full of home truths about the mendacity of public policy.”

Yep.

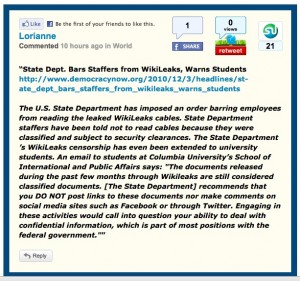

UPDATE: Interesting example of the State Department pressuring Columbia students against posting or discussing WikiLeaks stuff on Facebook:

In other words, if you want a job with Uncle Sam, lay off the WikiLeaks stuff.