Harvesting then and now

This remarkable 1565 painting by Pieter Breugel the Elder stopped me in my tracks the other day. It’s fascinating in its detail (for a much bigger version click on the image here) — right down to the people who may be skinny-dipping in a small lake in the far distance, the man bringing a pitcher of water to the others sitting under the tree, and the exhausted man asleep. But it’s also an interesting illustration of how agricultural practices have changed over the centuries.

Consider the number of people involved in harvesting that crop, and then look at this:

This field, which is farmed by a neighbour of ours, is truly vast — stretching almost as far as the eye can see. Yet its cereal crop was harvested in three days by two men (albeit with a couple of enormous machines). And then it was ploughed by a single man in a huge tractor in (I think) two days.

Quote of the Day

“If everyone is thinking alike, then no one is thinking”

- Benjamin Franklin

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Mark Knopfler | Ruth Moody | Wherever I Go

Long Read of the Day

Fixed Narratives, Fixing Narratives

Fabulous essay by Timothy Burke which starts with a scorching critique of the New York Times’s delusional (and dangerous) pursuit of editorial ‘balance’ at a time when that requires ‘balancing’ rational thinking and analysis with the ravings of a deluded ex-President and his supporting cast of right-wing nutters.

The NYT is really at its worst in this year’s campaign cycle, to the point that I’m a bit at a loss to imagine what’s going on in the newsroom. Their behavior is so programmatic that I have to think they’re consciously pursuing an obsessive, almost lunatic version of “balance” in their coverage of both presidential campaigns. It’s so over the top and calculated that it ends up feeling less like news coverage and more like an attempt to be a third side—not even being a referee but an advocate set against both campaigns on behalf of some imagined and very Rube Goldberg jerry-rigged “centrism”. Nate Cohn’s weird freak-out about how Harris was far to the left on economic policy right after she moved into the lead spot was a foretaste of what we’ve had ever since.

Today’s piece on why Harris is wrong that inflation has anything to do with price gouging is a good example of what this drive is doing to the clarity and structure of NYT news analysis. It’s not a patient laying out of the concept of inflation, nor an exploration of the history of inflation in post-Bretton Woods global economies. It’s not a methodical sector-by-sector look back at price increases during the pandemic and its immediate aftermath. It’s not a detailed analysis of whether there have been supply chain issues and which commodities have been affected most, or even what “supply chains” mean in the contemporary globalized situation, which is something quite different than what they meant in 1974, 1980, or 1990. The whole piece reads as if the conclusion was reached first and then the authors tried to find ways to make the conclusion hold. Which, I know, is not an unfamiliar habit in journalism or academia, but it’s a bad look when it is this obvious and this motivated.

Two junctures where I really found myself frustrated with the article was first that in fact some economists do say that “price gouging” and profit-seeking were one reason inflation remained high into 2022 and 2023. The article acknowledges that fact, but way down near the bottom of the inverted pyramid, whereas the lede frames the story as “politicians who have a message vs. the strong consensus of experts.” “Gouging” of some kind, fueled in part by the stimulus provided to consumers and nominal increases in wages in response to workers quitting their jobs, was so visible in 2022 and 2023 that some companies touted their continuing strategy of increasing prices to pad profits a part of their annual reports and have developed a marketing narrative to go along with it—that they want consumers to normalize a preference for “premium” brands where the main thing that’s premium about them is the price.

What really drove me nuts is a paragraph early on that sets out to rubbish the idea that companies are keeping supplies artificially low in order to pump demand and keep prices high. It drove me nuts first because there have been demonstrated cases of price manipulation of that kind in the last seventy-five years of global economic history. This is not folklore or conspiracy theory. Sometimes it’s not the companies, it’s speculative buyers that keep supplies low, but it absolutely can happen. More importantly, what the article offers as disproof that this was happening between 2021 and 2023 the following: “At least in theory, such a situation should be only temporary. New competitors should enter the market and provide products at a price people can afford.”

Among other things, the essay supports the view that if the US does finally sink into unshackled authoritarianism in November, then the country’s mainstream media will have — wittingly or unwittingly — been an accessory after the fact.

Books, etc.

Corporate BS

This looks interesting. Blurb reads:

From praising the health benefits of cigarettes to moralizing on the character-building qualities of child labor, rich corporate overlords have gone to astonishing, often morally indefensible lengths to defend their profits. Since the dawn of capitalism, they’ve told the same lies over and over to explain why their bottom line is always more important than the greater good: You say you want to raise the federal minimum wage? Why, you’ll only make things worse for the very people you want to help! Should we hold polluters accountable for the toxins they’re dumping in our air and water? No, the free market will save us! Can we raise taxes on the rich to pay for universal healthcare? Of course not—that will kill jobs! Affordable childcare? Socialism! It’s always the same tired threats and finger-pointing, in a concentrated campaign to keep wealth and power in the hands of the wealthy and powerful.

If in doubt, see Cory’s review!

My commonplace booklet

’Decisive moment’ 2.0

Many thanks to the readers who wrote to me after this pic headed Monday’s edition. Writing back to one of them (a fellow-photographer) I explained that it was the result of a conjunction of a few things: a lovely afternoon; me happening to be in the churchyard; I had a Leica with me (as usual); over to the left, out of view, was an almost extinct bonfire, smoke from which was gently drifting rightwards. The conjunction of all those things made for the ‘decisive moment’ that Henri Cartier-Bresson famously wrote about in his book of that title.

But when I raised the camera to my eye, the scene didn’t look right in colour. So I took out my iPhone, switched on its monochrome filter and took the picture.

“Ah”, wrote my friend, “the decisive moment! That time when you had a Leica and an iPhone and chose to use the iPhone…”. Touché.

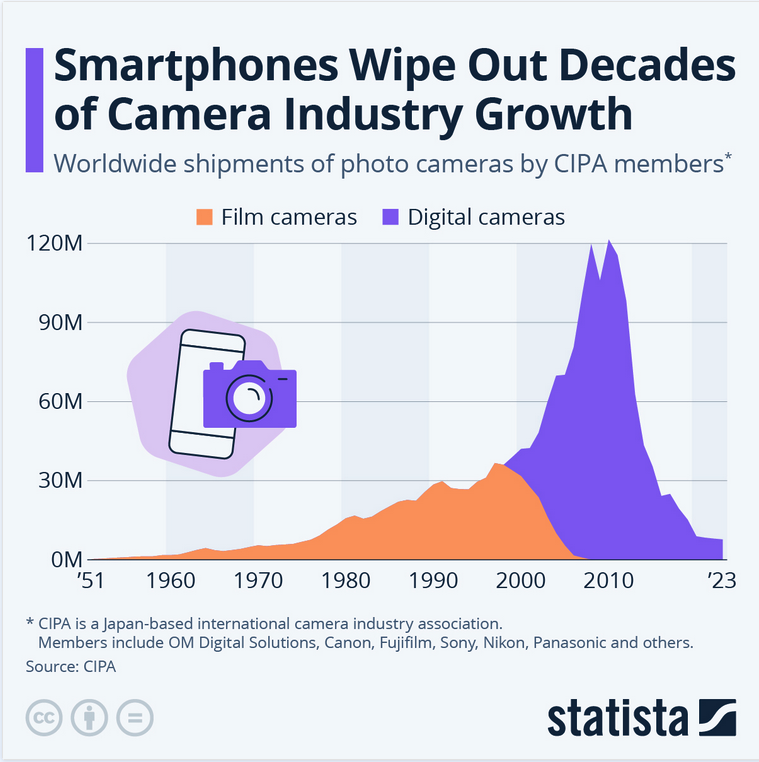

But actually, that particular decisive moment happened a long time ago. See this chart.

Most of those ‘digital cameras’ (blue colour) are in smartphones.

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 6am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already! hr>