High-tech minimalism

Without the vehicle on the left and the logo in the distance you’d never guess this was a service centre for cars.

Quote of the Day

”“What we are creating now is a monster whose influence is going to change history, provided there is any history left.”

- John Von Neumann on the digital computer

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Bill Evans | Waltz For Debby

Long Read of the Day

Cooking with Virginia Woolf

Marvellous essay by Valerie Strivers in the Paris Review arguing that the one flaw in Virginia Woolf’s great novel To the Lighthouse is that the author knows nothing about the dish that is a (perhaps the) central preoccupation of its central character, Mrs Ramsey.

The boeuf en daube in To the Lighthouse, a 1927 novel by Virginia Woolf about an English family on vacation in the Hebrides, is one of the best-known dishes in literature. Obsessed over for many chapters by the protagonist, Mrs. Ramsay, and requiring many days of preparation, it is unveiled in a scene of crucial significance. This “savory confusion of brown and yellow meats,” in its huge pot, gives off an “exquisite scent of olives and oil and juice.” It serves as a monument to the joys of family life and a celebration of fleeting moments. Thus, it is with fear and trembling that I suggest that Woolf’s boeuf en daube, from a cook’s perspective, is a travesty, and that its failures may prove instructive.

Ms Strivers even rounds off the piece with her own recipe for boeuf en daube. It looks convincing to me, and so I’m going to try making it — and, while I’m at it, also re-read the novel (which has always been one of my favourites).

En passant: The obvious explanation for Woolf’s ignorance in this matter, of course, is that she never appears to have done any cooking herself. At any rate her diaries are full of exasperated entries about the difficulties she has with her cook(s).

That’s typical of the Bloomsbury crowd, though, who (as the joke goes) “lived in squares and slept in triangles” — and, one could add, always had servants.

James Joyce’s modus operandi

(Alert: If Joyce isn’t your thing, avert gaze and skip this bit!)

There’s an interesting essay by Philip Keel Geheber in the LA Review of Books on the way Ulysses was written. It seems that Joyce was the worst nightmare of copy-editors and printers. Every time they sent him a proof, it came back much extended (as well as altered).

Joyce’s process was accretive, and he radically transformed Ulysses in 1921, while the manuscript was in proofs. During this late stage of production, he added one-third of the novel’s text in the margins of the typeset pages. But Joyce wasn’t adding text for the sake of length or difficulty, though these undeniably are effects of the additions; rather, fundamental characteristics of the novel’s episodes were bolstered at this stage. Joyce was no longer subject to deadlines and restrictions associated with serial publication. (This serialization abruptly ended following the first installment of “Oxen of the Sun” in the September–December 1920 issue of The Little Review, as the magazine suspended publication in preparation for the 1921 obscenity trial in the Southern District of New York.) With the author given time now to shape episodes in an open-ended fashion, the later sections of the book became much more complex and stylistically stranger.

Much of the book’s characteristic humor and allusiveness enters the novel in Joyce’s marginal scrawlings on the proof sheets. For instance, Bloom’s satirical commentary on the Latin Mass in “Lotus Eaters” is written at this stage…

Geheber is nothing if not thorough. He has a long analysis of the evolution of the famous 459-word rhapsodic passage in the “Ithaca” chapter on the qualities of water that Leopold Bloom admired.

“What in water did Bloom, waterlover, drawer of water, watercarrier, returning to the range, admire?” The drafted response is a short 58 words, with marginal inclusions of 36 words (indicated here between carets):

Yes, its universality ^and equality, ever seeking its own level, constant to its nature,^ its vastness in oceans ^on Mercalli’s projector^, its secrecy in springs ^such as the Hole in the Wall well by the Ashtown gate^, its healing virtues, its properties for washing, ^nourishing flowers & plants^ quenching thirst, and fire, it strength in hard hydrants, its docility in working millwheels, canals, electric power stations, ^its utility in bleachworks, tanneries, scutchmills,^ the fauna and flora it gave life to, its evil in marches, faded flowers, pestilent fens, stagnant pools when the moon waned.

Joyce transferred these 94 words directly to the Rosenbach manuscript — his mostly legible manuscript draft, from which typescripts were produced — adding another 76 words in the margins and drafting a 117-word block on the facing page. To these now 283 words, Joyce added another 176 in the margins of the proofs, so that 38 percent of the water hymn’s total length was produced in the waning months of 1921.

Like I said: a copy-editor’s nightmare. But also a genius.

My commonplace booklet

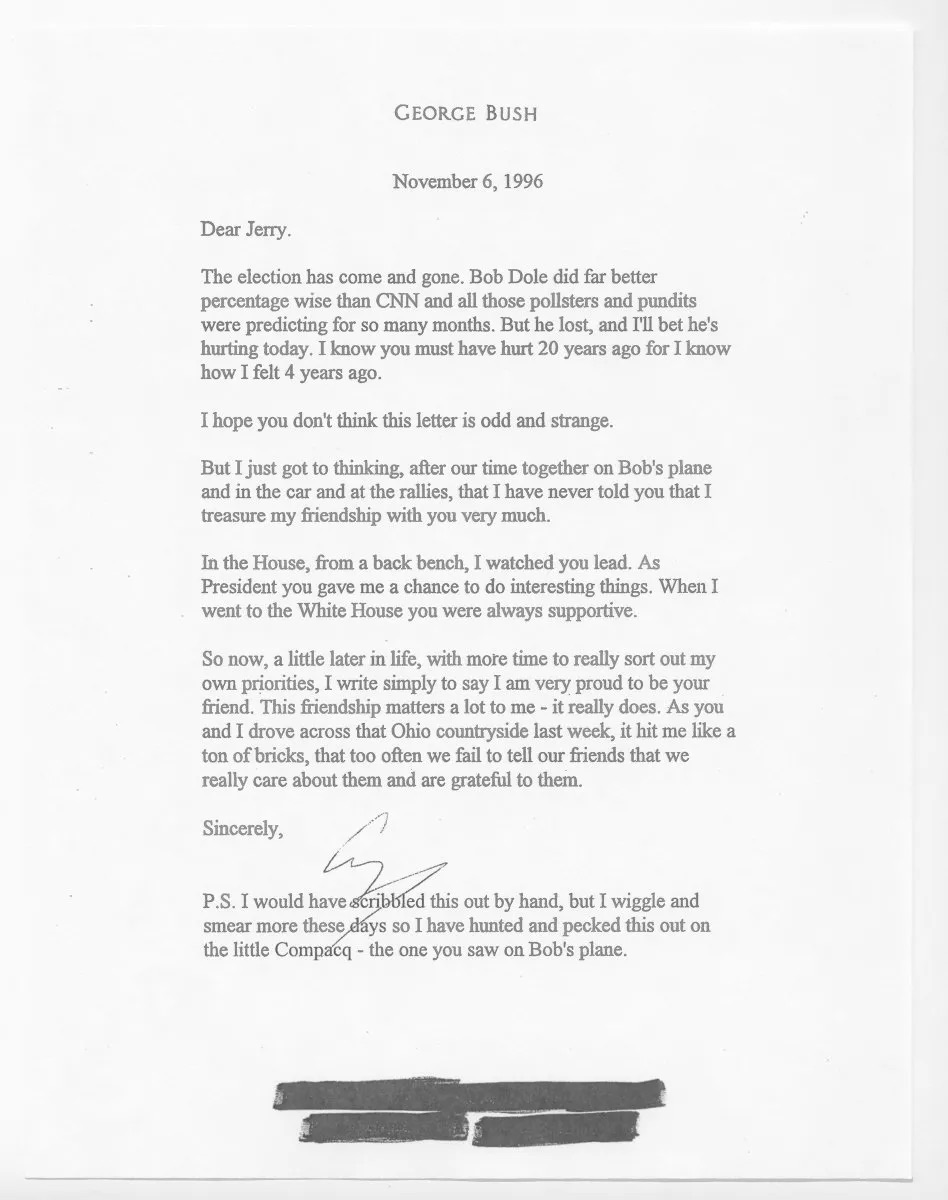

How Presidents used to write to one another

From George Bush Senior to Gerald Ford…

This Blog is also available as a daily email. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!