Coffeehouse art

Quote of the Day

“Eternal truths are always hypothetical.”

- Bertrand Russell

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Beniamino Gigli | O sole mio

If you think this is corny then you ain’t heard nothing yet. Many years ago, I made my first trip to Venice. It was in November and I was on my own, and knew nothing about the city save what I had read in newspapers. (You know the old jokes — like the one about the Hearst correspondent who arrived and was taken aback by the place. He cables back to base: “STREETS FULL OF WATER STOP PLEASE ADVISE”. Alas, I can never remember the reply.)

Anyway, after I’d checked into my hotel, I went for a walk, and promptly got lost. And then, as I blundered down a narrow alleyway, I heard someone singing this in faux-Gigli style, vibrato and all. I turned a corner, came to a canal and saw one of those plush black gondolas, in which reclined an affluent couple while they were serenaded by the gondolier. And I remember thinking: you couldn’t make this up.

When I got home I told my kids about it. They refused to believe the gondolier was singing O sole mio. He was, they explained, singing “Just one Cornetto”, as sung by a gondolier in an ice-cream ad then popular on British TV.

Long Read of the Day

What neo-Luddites get right — and wrong — about Big Tech

Is AI the latest threat to livelihoods? That depends on society

Characteristically thoughtful column by Tim Harford in the Financial Times and hopefully outside the paywall.

If it’s not, the paragraphs below contain the gist.

Neo-Luddites can take inspiration from John Booth, a 19-year-old apprentice who joined a Luddite attack on a textile mill in April 1812. He was injured, detained and died after being allegedly tortured to give up the identity of his fellow Luddites. Booth’s last words became a legend: “Can you keep a secret?” he whispered to the local priest, who attested that he could. The dying Booth replied, “So can I.” But it was Booth’s earlier words which deserve our attention. The new machinery, he argued, “might be man’s chief blessing instead of his curse if society were differently constituted”.

In other words, whether new technology helps ordinary citizens depends not just on the nature of the technology but on the nature of the society in which that technology is developed and deployed. Acemoglu and Johnson argue that broad-based flourishing is currently eluding us, just as it eluded the workers of the early industrial revolution.

Worth reading in full if it’s available.

Books, etc.

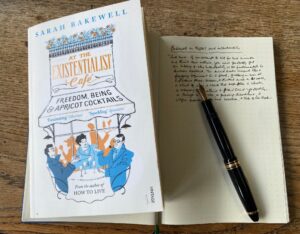

I’ve been reading — and enjoying — Sarah Bakewell’s lovely book on existentialism and its adherents. I got it partly because my late wife Carol and I were fascinated by existentialist ideas when we were students (and she took it further by writing a M. Litt thesis on Simone de Beauvoir’s autobiography, and even interviewed the Grande Dame herself in her Paris apartment).

Years ago I had read (and also enjoyed) Bakewell’s book on Montaigne — from which I came away with the idea that he could be seen as the first blogger. She’s very good at untangling and explaining abstract philosophical ideas. Here she is, for example, early in the new book, on Husserl’s emphasis of the importance of intentionality — the fact that when we think, we are always thinking about something.

Just try it: if you attempt to sit for two minutes and think about nothing, you will probably get an inkling of why intentionality is so fundamental to human existence. The mind races around like a foraging squirrel in a park, grabbing in turn at a flashing phone–screen, a distant mark on the wall, a clink of cups, a cloud that resembles a whale, a memory of something a friend said yesterday, a twinge in the knee, a pressing deadline, a vague expectation of nice weather later, a tick of the clock. Some Eastern meditation techniques aim to still this scurrying creature, but the extreme difficulty of this shows how unnatural it is to be mentally inert. Left to itself, the mind reaches out in all directions as long as it is awake – and even carries on doing it in the dreaming phase of sleep.

Re her earlier book on Montaigne: in a nice coincidence, my friend and colleague David Runciman picked one of his essays — the longest and most puzzling one — as his subject for the first episode in his new ‘History of Ideas’ podcast series.

My commonplace booklet

AI-powered Photoshop

I don’t use Photoshop, or do fakery, but if I did I’d be interested in this.

This Blog is also available as a daily email. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!