Brooding on conversations I’ve had this week with some of this Term’s Press Fellows about the process of writing, I came on “Lies, manuscripts and icebergs: how I’ve written two novels” by Naomi Wood, who teaches creative writing at Goldsmiths College, University of London. At one stage, she writes:

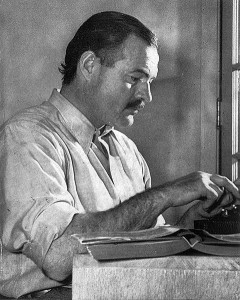

During the first draft I can’t spend longer than three hours writing a day. After that I want to do what Hemingway did – give up at noon and go sailing on my nonexistent boat, fishing for marlin with a daiquiri by my side. Plus, it usually reads awfully – the language is all over the place, the metaphors in thickets, the plotting heavy-handed as if done by a child. All I’m doing is telling, not showing, because I don’t know yet what I’m even telling, so how can I begin to represent that through showing?

If I’m feeling particularly bummed at this stage I sometimes cast my eye over some photocopies I have of Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises manuscript. What I love is all the crossings-out, the bruise of the pen across the page, the margins packed with stuff that came later. It reminds me that no-one got it right the first time around; that books are built from accretions of drafts. Its final effortlessness betrays effort.

I’m sure that’s true, though Sam Johnson said it more elegantly when he observed that “nothing that is read with pleasure was written without pain”.

Naomi’s right about Hemingway, IMHO. Here’s the first page of A Farewell to Arms:

In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across theriver and the plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels. Troops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees. The trunks of the trees too were dusty and the leaves fell early that year and we saw the troops marching along the road and the dust rising and leaves, stirred by the breeze, falling and the soldiers marching and afterward the road bare and white except for the leaves.

The plain was rich with crops; there were many orchards of fruit trees and beyond the plain the mountains were brown and bare. There was fighting in the mountains and at night we could see the flashes from the artillery. In the dark it was like summer lightning, but the nights were cool and there was not the feeling of a storm coming.

Sometimes in the dark we heard the troops marching under the window and guns going past pulled by motor-tractors. There was much traffic at night and many mules on the roads with boxes of ammunition on each side of their pack-saddles and gray motor-trucks that carried men, and other trucks with loads covered with canvas that moved slower in the traffic. There were big guns too that passed in the day drawn by tractors, the long barrels of the guns covered with green branches and green leafy branches and vines laid over the tractors. To the north we could look across a valley and see a forest of chestnut trees and behind it another mountain on this side of the river. There was fighting for that mountain too, but it was not successful, and in the fall when the rains came the leaves all fell from the chestnut trees and the branches were bare and the trunks black with rain. The vineyards were thin and bare-branched too and all the country wet and brown and dead with the autumn. There were mists over the river and clouds on the mountain and the trucks splashed mud on the road and the troops were muddy and wet in their capes; their rifles were wet and under their capes the two leather cartridge-boxes on the front of the belts, gray leather boxes heavy with the packs of clips of thin, long 6.5 mm. cartridges, bulged forward under the capes so that the men, passing on the road, marched as though they were six months gone with child.

There were small gray motor-cars that passed going very fast; usually there was an officer on the seat with the driver and more officers in the back seat. They splashed more mud than the camions even and if one of the officers in the back was very small and sitting between two generals, he himself so small that you could not see his face but only the top of his cap and his narrow back, and if the car went especially fast it was probably the King. He lived in Udine and came out in this way nearly every day to see how things were going, and things went very badly.

At the start of the winter came the permanent rain and with the rain came the cholera. But it was checked and in the end only seven thousand died of it in the army.

Somerset Maugham, who was an astonishingly successful writer in the 1930s, once revealed that before he embarked on a new book, he always re-read Voltaire’s Candide as a way of cleansing his palate, as it were. I’ve known other writers who start by re-reading Evelyn Waugh for the same reason. But, for my money, Hemingway beats them all.