The Swiss Park in Versailles, on a peaceful Sunday morning walk.

Quote of the Day

”There are no credentials. They do not even need a medical certificate. They need not be sound either in body or mind. They only require a certificate of birth — just to prove that they were the first of the litter. You would not choose a spaniel on those principles.

- Lloyd George on the House of Lords, 1909.

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Schubert, Trio op. 100 – Andante con moto

Long Read of the Day

What We Want Doesn’t Always Make Us Happy

Nice Bloomberg column by Noah Smith.

There’s no clear consensus on how to measure happiness. Some neuroscientists have tried to link it to various measures of brain activity. But economists tend to use a method that’s a lot cheaper and quicker — they send out surveys and questionnaires asking people how happy they are.

Happiness research has led to some surprising and troubling discoveries. People seem to reliably seek out a few things that make them unhappy…

(Spoiler alert: it’s about a certain social media company).

Fast Food in Pompeii

Well, what do you know? According to the Guardian an “exceptionally well-preserved snack bar” has been unearthed in Pompeii!

Researchers said on Saturday they had discovered a frescoed thermopolium or fast-food counter in an exceptional state of preservation in Pompeii. The ornate snack bar, decorated with polychrome patterns and frozen by volcanic ash, was partially exhumed last year but archaeologists extended work on the site to reveal it in its full glory. Pompeii was buried in ash and pumice when the nearby Mount Vesuvius erupted in AD79, killing between 2,000 and 15,000 people. Archaeologists continue to make discoveries there.

At first sight it looks like one of those counters in supermarkets where you make up your own pizza toppings — except that Tesco & Co don’t do classy frescoes. And of course you’re unlikely to be interrupted by a volcanic explosion.

What comes after Google search?

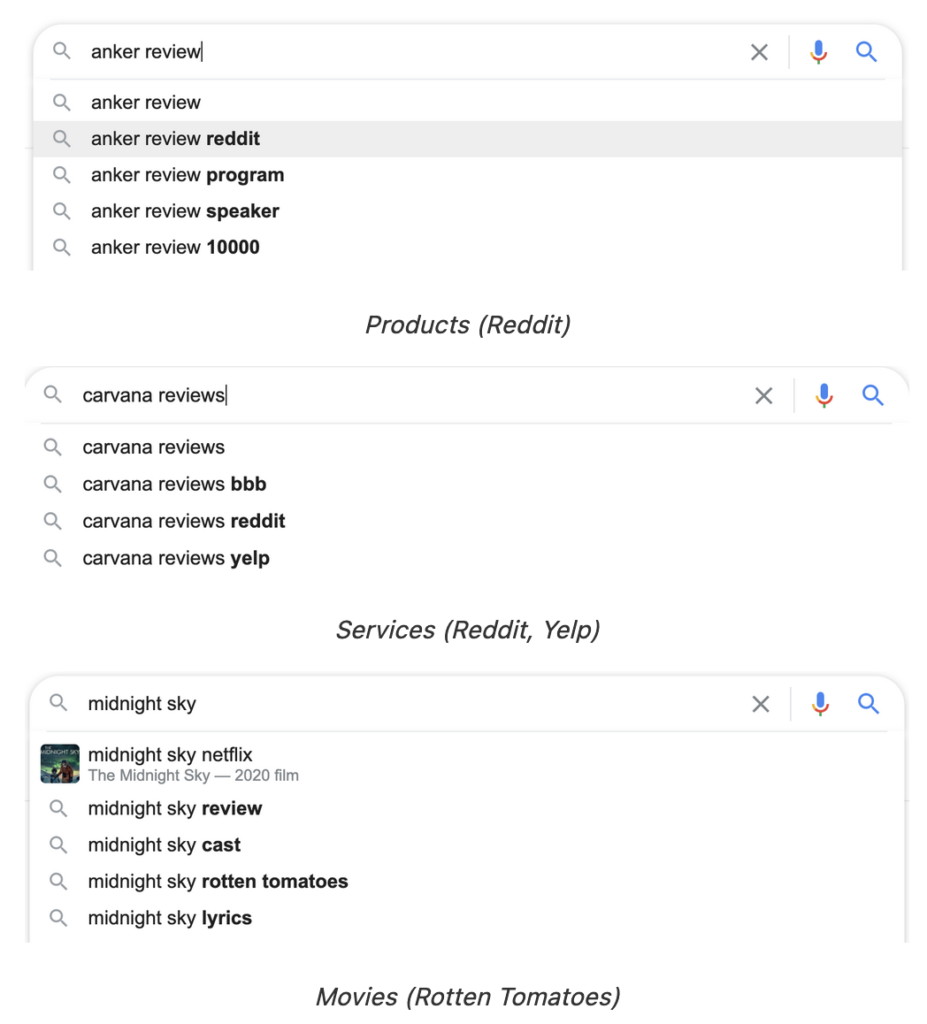

Nobody knows, but there are signs that Google isn’t hitting the spot any more. Daniel Gross has an interesting blog post about this.

In 2000, Google got popular because hackers realized it was better than Lycos or Excite. This effect is happening again. Early adopters aren’t using Google anymore.

They aren’t using DuckDuckGo either. They’re still using Google.com, but differently. To make Google usable, users are adding faux-query modifiers that to supress the “garbage Internet”.

You see this in the typeahead logs.

Gross has noticed also that more advanced users use modifiers like “site: filetype: intitle:” because adding “reddit” isn’t strict enough, because spammy websites often manipulate content to optimise their search results. Or searches for “Reviews UPDATED JANUARY 2020” exploit the fact that customers suffix queries with the year. What such experienced searchers are looking for is freshness, not a title match. “Something’s broken”, he says, “and a tiny share of Google is open for the taking”. A tiny bit in this context could be an awful lot.

One of the interesting things about this is that it reminds one of how much craft knowledge there is in using an established search engine well. I like to think I’m an experienced user, but there are often times when some of my smarter colleagues can find what I’ve failed to unearth. Which suggests there might be an opening not just for a specialised alternative to Google but also for a good course on ‘Advanced Search with [name your engine]’. Probably they already exist and I just can’t be bothered to Google them!

How to mark a fateful transition

Since next Sunday’s edition of the Observer will be published in a United Kingdom that is no longer a member of the European Union, today’s issue has gone to town on marking the significance of the change. As someone who has happily written for the paper for a long time (I think my first piece was published in 1982) I’m obviously biased, but I think that today’s edition is really special.

Just to pick some examples at random…

Tim Adams has a terrific long essay reflecting on how we got to this point.

One of the pointed ironies of the long farewell of Brexit has been that nothing has become the EU quite like Britain’s leaving it. Having tried hard for 70 years to find a single theme that unites the disparate nations of the continent, the EU has finally discovered common cause in the spectacle of serial foot-shooting that has marked Britain’s efforts to depart. As delay led to extension and to prorogation, the approval ratings for the EU never soared so high. Guy Verhofstadt, the Brexiters’ pantomime villain in Brussels, told me last year that Britain has come to represent to Europeans the consequences of not standing up to divisive populism. “You want to see what nationalism does? Come to London.”

The sadness of that observation is a reminder of Britain’s failure to bring to Europe the values with which we were once more clearly associated: democracy, scrutiny, a robust sense of fair play. Rather than successive governments insisting on a semi-detached “we know best” approach to Europe, for fear of riling the tabloid press, there would have been more courage in wholeheartedly engaging to reform its institutions. Britain, in retrospect, perhaps always flirted with crashing out because it misunderstood Europe from the start.

One of the points Tim makes is that just because the UK has left doesn’t mean that it can forget about the EU. This is spelled out in a sober, informative piece by Sam Lowe, a Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for European Reform. The UK may have won the power to diverge from EU rules, he points out, but the new relationship will be one of constant renegotiation. The Trade Deal, for example,

marks just the beginning of the UK’s new relationship with the EU, and will inevitably evolve over time. Next year, for example, the UK will need to decide whether to link its own domestic carbon-pricing scheme with the EU’s, find out whether the personal data of EU citizens can still be stored on UK servers, and re-enter discussions on the working of the sea border between Northern Ireland and Great Britain.

There is also the outstanding question of financial services equivalence – a unilateral EU decision whether to allow certain UK-based financial businesses to continue selling directly to EU-based clients. Even if such permission is granted, we should not assume it will be permanent.

The UK will also need to decide whether to use the new-found freedom to diverge from EU rules and approaches, and if so whether it is willing to accept the consequences of doing so. If it chooses to do so, years and years of disputes and reviews await.

In the longer term, it is inevitable that every successive UK government will want to renegotiate, or alter, aspects of the relationship with the EU…

If one adopts the ‘divorce’ metaphor which has been endlessly popular with the British tabloids, the UK has got its Decree Nisi. Now comes the awkward period of finding a working relationship. Who picks up the kids from school? What happens at Half Term? What happens with one of the parents is ill? And how to handle Christmas?

There’s also a lovely piece by the Irish journalist Fintan O’Toole, who had been a merciless critic of the Brexit shambles from the very beginning. In today’s essay, headlinded “So long, we’ll miss you – we Europeans see how much you’ve helped to shape us”, he points out the ways in which the UK helped shape the EU about which it always seems to be ambivalent.

The single market is the EU’s great achievement – protecting it was, ironically, the overwhelming aim in the negotiations on future trade with the UK. It simply would not have happened, when it happened, if Margaret Thatcher had not pressed so hard. It is easy to forget – because it has suited almost every side to do so – that the blueprint for the single market was a booklet called Europe – The Future that Thatcher presented to her fellow leaders at the Fontainebleau summit in 1984.

The problem was that Thatcher could never accept that the workings of a single market would have to be counterbalanced by common social, environmental and safety standards, with the political, legal and administrative capacity to enforce them. The fact remains: the force that has shaped the EU for the past 30 years was set in motion by Britain.

Equally, without Britain, it is not at all obvious that the EU would have responded so boldly to the fall of the Berlin Wall by bringing the Warsaw Pact states into its fold. Again, it was Thatcher who proclaimed the goal of enlargement in her Bruges speech in 1988. It was under a British presidency that talks on membership were opened with the first wave of central European states. It was Tony Blair who later pushed for Romania and Bulgaria to be allowed to join. Here, too, the implications of a British policy were not really understood in Britain. It was not explained that free movement would mean more immigration from these countries. Or that the governance of a much bigger EU would inevitably have to be more closely co-ordinated. Nonetheless, on these two defining issues, Britain was adventurous, ambitious, energetic and effective.

History, says O’Toole, will judge that the long relationship between the UK and Europe has been good for both. So now is the time to forget the rancorous parting and get on with life. He’s right.

This blog is also available as a daily email. If you think this might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-click unsubscribe if you decide that your inbox is full enough already!