David Remnick, writing in the New Yorker:

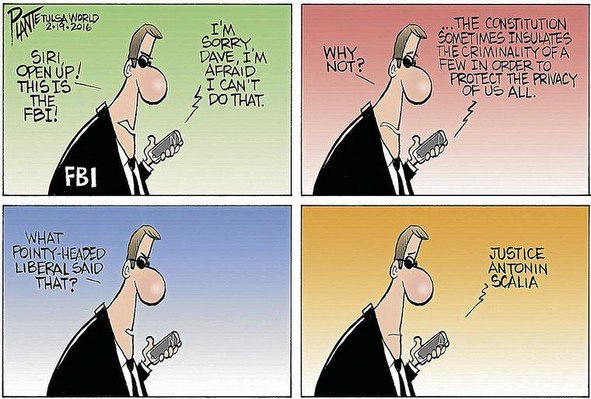

Trump is no longer hustling golf courses, fake “universities,” or reality TV. He means to command the United States armed forces and control its nuclear codes. He intends to propose legislation, conduct America’s global affairs, preside over its national-intelligence apparatus, and make the innumerable moral and political decisions required of a President. This is not a Seth Rogen movie; this is as real as mud. Having all but swept the early Republican primaries and caucuses, Trump—who re-tweets conspiracy theories and invites the affections of white-supremacist groups, and has established himself as the adept inheritor of a long tradition of nativism, discrimination, and authoritarianism—is getting ever closer to becoming the nominee of what Republicans like to call “the party of Abraham Lincoln.” No American demagogue––not Huey Long, not Joseph McCarthy, not George Wallace––has ever achieved such proximity to national power.

Yep. Trump is all of a piece with the wave of authoritarians and xenophobes who have swept to power in Russia, Poland and Hungary and who loiter at the gates of power in France.

It may be that Trump would lose when the process moves beyond the primaries and the nomination and on to the general election. But it suddenly begins to look a lot scarier. As Tom Friedman observed the other day, a fraudulent “move to the centre” is not beyond Trump’s ingenious, manipulative mind.

It’s easy to ‘explain’ Trump’s ascendancy in terms of the politics of outrage — the rage of people who have been screwed by globalisation and blame the deterioration in their lives on that and on immigration. But, Remnick argues, the story goes back further than that. “The G.O.P. establishment may be in a state of meltdown”, he writes,

but this process of exploiting the darkest American undercurrents began with Richard Nixon’s Southern Strategy and, more lately, has included the birther movement and the Obama Derangement Syndrome. Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz, who compete hard for the most extreme positions in conservatism, decry the viciousness and the vacuousness of Trump, but they started out by deferring to him––and now they ape his vulgarity in a last-ditch effort to keep pace. Insults. Bigotry. Nationally televised assurances of adequate genital dimensions. This is the political moment in which we live. The Republican Party, having spent years courting the basest impulses in American political culture, now sees the writing on the wall. It reads “Donald Trump,” in very big letters.

If this farce pans out as I fear, then the US (and, by implication, the rest of us) could find ourselves in a very strange place. It’s still possible, for example, that Hillary Clinton could be indicted for her amazingly reckless use of a private email server. In which case, what happens? My guess that it might eventually come down to a last minute run by Michael Bloomberg as an independent. I hold no candle for him, but he has held serious public office. And he’s not crazy.