Mellow fruitfulness

Our small vineyard is coming along nicely.

Quote of the Day

“Even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: Its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.”

- Walter Benjamin, in The Work of Art in the Age of its Technical Reproducibility

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Fredrik Pacius | Studentsång

It’s in Finnish (obviously), but I think it’s a student song for Mayday.

Long Read of the Day

Asking the wrong questions

Lovely essay by Benedict Evans arguing that “with fundamental technology change, we don’t so much get our predictions wrong as make predictions about the wrong things”.

The essay opens with a story about his grandfather, Will Jenkins.

In 1946, by which time he’d become a notable writer of science fiction, he published a story called ‘A Logic named Joe’, which described a global computer network with servers and terminals, that starts giving people the information that it thinks they ought to know as opposed to waiting for them to search for it – the Singularity, if you like, or maybe just Alexa. He also, as I recall, predicted reality TV somewhere.

And yet, despite predicting half of our world, as a father in the 1950s he could not imagine why his daughter – my mother – wanted to work.

This isn’t an uncommon observation – plenty of people have pointed out that vintage scifi is full of rocketships but all the pilots are men. 1950s scifi shows 1950s society, but with robots. Meanwhile, the interstellar liners have paper tickets, that you queue up to buy. With fundamental technology change, we don’t so much get our predictions wrong as make predictions about the wrong things. (And, of course, we now have neither trolleys nor personal gliders.)

I was reminded of this photo recently when I came across a RAND ‘long-range forecasting’ study, from 1964…

Do read on. Evans is an elegant, thoughtful writer, and one of the most acute observers of the tech industry.

It’s useful that Strawberry can ‘think’, but we need to know its reasoning

Yesterday’s Observer column

It’s nearly two years since OpenAI released ChatGPT on an unsuspecting world, and the world, closely followed by the stock market, lost its mind. All over the place, people were wringing their hands wondering: What This Will Mean For [enter occupation, industry, business, institution].

Within academia, for example, humanities professors agonised about how they would henceforth be able to grade essays if students were using ChatGPT or similar technology to help write them. The answer, of course, is to come up with better ways of grading, because students will use these tools for the simple reason that it would be idiotic not to – just as it would be daft to do budgeting without spreadsheets. But universities are slow-moving beasts and even as I write, there are committees in many ivory towers solemnly trying to formulate “policies on AI use”.

As they deliberate, though, the callous spoilsports at OpenAI have unleashed another conundrum for academia – a new type of large language model (LLM) that can – allegedly – do “reasoning”. They’ve christened it OpenAI o1, but since internally it was known as Strawberry we will stick with that…

Books, etc.

From the blurb:

In The Tech Coup, Marietje Schaake offers a behind-the-scenes account of how technology companies crept into nearly every corner of our lives and our governments. She takes us beyond the headlines to high-stakes meetings with human rights defenders, business leaders, computer scientists, and politicians to show how technologies—from social media to artificial intelligence—have gone from being heralded as utopian to undermining the pillars of our democracies. To reverse this existential power imbalance, Schaake outlines game-changing solutions to empower elected officials and citizens alike.

Schaake — formerly a Dutch MEP — is one of the few politicians who understood the tech industry and was sceptical of, and watchful of, Zuckerberg & Co. In recent years, she’s been a Fellow at the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI. Her book is a must-read for those who, like me, are condemned to watch this industry.

My commonplace booklet

As long-term readers will know I’ve always been fascinated by John Maynard Keynes. (In a way, if you live and work in Cambridge it’s hard not to be.) But Adam Tooze (who used to be an academic here and is now in Columbia) has a fascinating item on Keynes in his Substack. It’s about an essay that Keynes contributed in 1909 as a young man to the Cambridge Apostles with the intriguing title: “Can We Consume Our Surplus? or The Influence of Furniture on Love”. The post goes on to give the full text of the paper.

“Does it really make a great difference to us,” Keynes asks at one point,

in what rooms we live, whether we clothe them with chintz or with velvet, whether they are hard or padded? That it makes a difference in some ways, is obvious. These things affect our pleasure and our convenience. But do they do more than this? Do they suggest to us thoughts and feelings and occupations?

The effect on us of their external architecture is, I believe, much slighter than their internal proportions. I myself have spent most of my life inside buildings which are as pompous as possible. But what effect has a flitting between Eton, King’s, and Whitehall had? People who live in the Great Court at Trinity are very different beings from those who live in the Fellows’ Buildings at King’s. But I put it down to the inside shapes of the rooms, much more than to the different look outs. And it is consistent with this that those who live in the little rooms in Neville’s Court are not so very different from themselves in the Great Court.

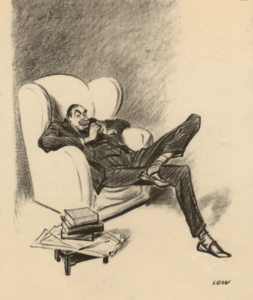

The essay also has that lovely cartoon by Low of Keynes lounging in a well-upholstered armchair. It comes after this observation:

Our furniture is, after all, very unimportant, and leaves us very much where we should be without it. But I don’t think it is quite true. Our furniture may be the best we can do, and yet we may deserve something much better.

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 6am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!