Quote of the Day

”Only two rules of drama criticism matter. One. Decide what the playwright was trying to do, and pronounce well he has done it. Two. Determine whether the well-done thing was worth doing at all.”

- James Agate

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Beethoven | Romance for Violin and Orchestra No. 2 in F major, Op. 50 | Kurt Masur & Renaud Capuçon

Lovely at any time and place, but this is a special performance. It took place in the Church of St. Nicolai in Leipzig to mark the city’s commemoration of the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Long Read of the Day

Winning the Game You Didn’t Even Want to Play: On Sally Rooney and the Literature of the Pose

Stephen Marche on the slow abandonment of ‘Literary Voice’.

Thanks to Chris Cantrell for alerting me to it.

Want to save the Earth? Then don’t buy that shiny new iPhone

Yesterday’s Observer column:

On Tuesday, Apple released its latest phone – the iPhone 13. Naturally, it was presented with the customary breathless excitement. It has a smaller notch (eh?), a redesigned camera, Apple’s latest A15 “bionic” chipset and a brighter, sharper screen. And, since we’re surfing the superlative wave, the A15 has nearly 15bn transistors and a “six-core CPU design with two high-performance and four high-efficiency cores”.

Wow! But just one question: why would I buy this Wundermaschine? After all, two years ago I got an iPhone 11, which has been more than adequate for my purposes. That replaced the iPhone 6 I bought in 2014 and that replaced the iPhone 4 I got in 2010. And all of those phones are still working fine. The oldest one serves as a family backup in case someone loses or breaks a phone, the iPhone 6 has become a hardworking video camera and my present phone may well see me out.

That’s three phones in 11.5 years, so my “upgrade cycle” is roughly one iPhone every four years. From the viewpoint of the smartphone industry, which until now has worked on a cycle of two-yearly upgrades, I’m a dead loss…

Do read the whole thing.

Clive Sinclair RIP

He was easy to laugh at, and sometimes not easy to like, but his ZX Spectrum was the first personal computer that many of us bought, and it was one of the devices that sparked the extraordinary growth of the computer games industry in the UK.

The Guardian had a nice obituary of him which, I think, got it right. He was, it said, “one part visionary, one part dotty uncle and one part marketing genius”.

Sinclair had achieved his ambition of producing a computer for less than £100 but it was very basic, needing to be plugged into the television to provide a screen and with a cassette to store data. A year later came the ZX81 and then, marginally more sophisticated, and costing £125, the ZX Spectrum, which was made under licence in the US by Timex.

With no commercial rivals initially, the machines sold in their thousands – a quarter of a million of the 1981 model in the first year – and the company’s profits soared. By 1982 it was making £8.55m on a turnover of £27m; a year later the company was valued at £136m and the profits had reached nearly £20m. If many owners and their children used their computers to play new sorts of games such as Monster Maze, they were also taught about programming and other technological skills.

The BBC made a documentary — Micro Men — which nicely captures the atmosphere of the age nicely — and is available on YouTube.

And it’s worth remembering that he accurately foresaw the advent of the EV.

How to review a book, #245

Lovely essay by Scott Alexander on Martin Gurri’s excitable book — The Revolt of the Public and the Crisis of Authority in the New Millennium — the first edition of which I read in 2014 and promptly forgot about.

But Scott Alexander picked it up recently and did a sardonic demolition job on its second edition. This is how it begins:

Martin Gurri’s The Revolt Of The Public is from 2014, which means you might as well read the Epic of Gilgamesh. It has a second-edition-update-chapter from 2017, which means it might as well be Beowulf. The book is about how social-media-connected masses are revolting against elites, but the revolt has moved forward so quickly that a lot of what Gurri considers wild speculation is now obvious fact. I picked up the book on its “accurately predicted the present moment” cred, but it predicted the present moment so accurately that it’s barely worth reading anymore. It might as well just say “open your eyes and look around”.

And this is how it concludes:

The one exception to my disrecommendation is that you might enjoy the book as a physical object. The cover, text, and photographs are exceptionally beautiful; the cover image – of some sort of classical-goddess-looking person (possibly Democracy? I expect if I were more cultured I would know this) holding a cell phone – is spectacularly well done. I understand that Gurri self-published the first edition, and that this second edition is from not-quite-traditional publisher Stripe Press. I appreciate the kabbalistic implications of a book on the effects of democratization of information flow making it big after getting self-published, and I appreciate the irony of a book about the increasing instability of history getting left behind by events within a few years. So buy this beautiful book to put on your coffee table, but don’t worry about the content – you are already living in it.

Delicious!

Books really do furnish a Zoom

During the first Covid lockdown I kept a daily audio diary for the first 100 days and on May 12, 2020 (which was Day 52) I talked about the conversations I’d had with colleagues about the wall of books in my study that was the background to all of my online encounters.

Shortly afterwards I had a nice email from James Mackay, who edits The Penguin Collector, a lovely twice-yearly journal of the Penguin Collectors Society, asking for permission to reproduce the transcript of the audio — which I was happy to give. The June 2021 issue has now arrived, and very nice it is too. If you’re interested, here’s the audio:

And if you’re busy, here’s the transcript:

May 12: Day 52

Like many people, I’m spending too much time on Zoom. I’ve even set up a Zoom station in my study, so that when a meeting is due I just go to that part of the room, log into to the Mac that sits there with Zoom running, and start. No fiddling with laptops or microphones for me. Straight down to business. I’m lucky enough to have a very large study. The guy from whom we bought the house many years ago was an architect, and he ran a successful practice from this room. So it’s big and airy. And it’s lined with books for the very simple reason that I have a book habit. So my background for the purposes of Zoom is a wall of books. This often gives rise to comment in the smalltalk that goes on while people are waiting for others to join the call. Have I read all those books, I am asked?

I’m about to respond indignantly, and then I think of Flann O’Brien, one of the funniest Irish writers of the 20th century. His actual name was Brian O’Nolan, but he wrote under pen names because in real life he was a fairly senior civil servant in the government of the Irish Free State, as the Republic was then known. His other pen-name was Myles na Gopaleen, under which moniker he had a regular column in the Irish Times — a “black protestant newspaper,” as my devoutly Catholic mother used to call it — a column that was so surreal that it made Salvador Dali look like Spinoza. Flann used the column for many purposes, but one of them was to publish prospectuses for the numerous wacky businesses he had dreamed up. And one of these involved books. It all started with a visit he made to the new house of a friend of “great wealth and vulgarity”.

After kitting out the house, his friend decided that it needed books — because, as is well known, books really do furnish a room. “Whether he can read or not, I do not know,” wrote Flann, “but some savage faculty for observation told him that most respectable and estimable people usually had a lot of books in their houses. So he bought several bookcases and paid some rascally middleman to stuff them with all manner of new books, some of them very costly volumes on the subject of French landscape painting.” “I noticed,” Flann continued, “that not one of them had ever been opened or touched, and remarked on the fact.” “When I get settled down properly,” said his friend, “I’ll have to catch up on my reading”.

At this point Flann had an epiphany. “Why should a wealthy person like this be put to the trouble of pretending to read at all? Why not have a professional book handler to go through and maul his library for so-much per shelf? Such a person, if properly qualified, could make a fortune.”

Thus was born the concept of a book handling service. Its founder envisaged four levels of handling. The lowest was ‘Popular Handling’: “each volume to be well and truly handled, four leaves in each to be dog-eared, and a tram ticket, cloakroom docket or other comparable item inserted in each as a forgotten bookmark. Say £1 7s 6d. Five percent discount for civil servants.”

Next level up was ‘Premier handling’: “Each volume to be thoroughly handled, eight leaves in each to be dog-eared, a suitable passage in not less than 25 volumes to be underlined in red pencil, and a leaflet in French on the works of Victor Hugo to be inserted as a forgotten bookmark in each. Say, £2 17s 6d. Five per cent discount for literary university students, civil servants and lady social workers.”

Two — even more sophisticated — levels of service were envisaged: ‘De Luxe’ (which included five volumes to be inscribed with the forged signatures of their authors). And then there was the ‘Handling Superb’ service. You can imagine what that involved.

So perhaps you can see why I think of Flann whenever I look at my background during an online meeting. Those books have been well and truly handled. And he would have known that books really do furnish a Zoom.

Btw, the whole diary is available as a Kindle book.

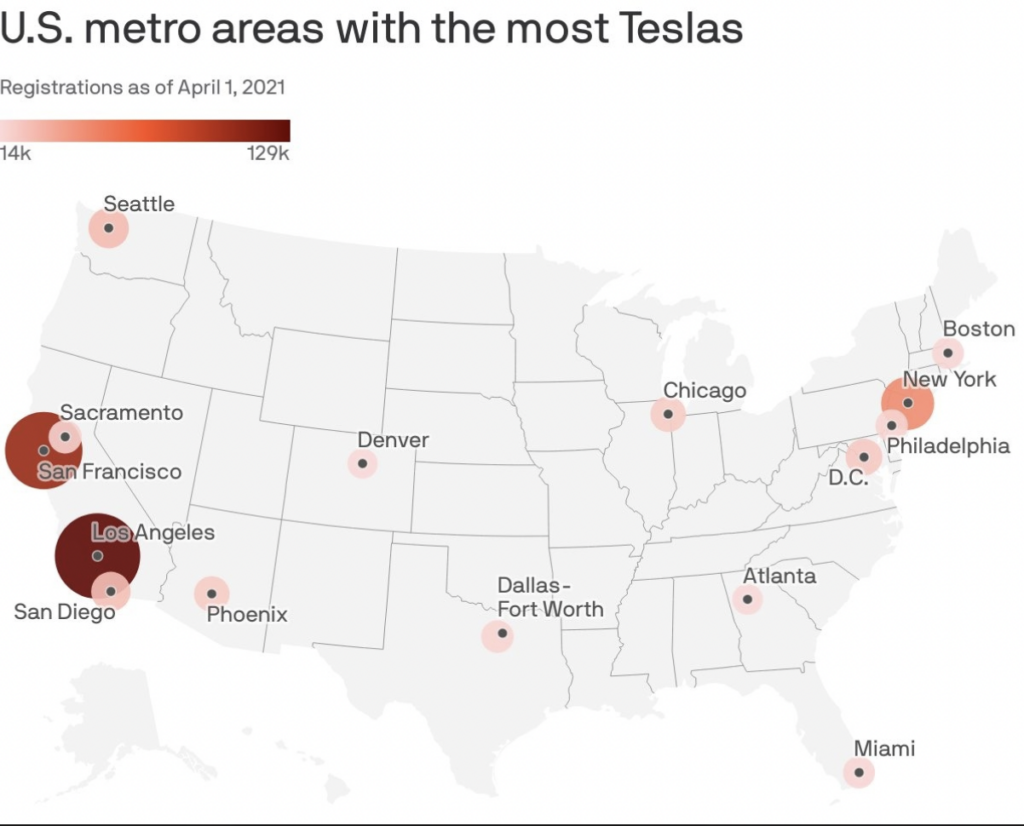

Chart of the Day

Interesting (and predictable) map. Suggests that the fly-over states are all waiting for the Ford F-150 Lightning!

This blog is also available as a daily newsletter. If you think this might suit you better why not sign up? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox at 7am UK time. It’s free, and there’s a one-button unsubscribe if you conclude that your inbox is full enough already!