The New Yorker carried an elegant tribute to Irving Penn by Adam Gopnik.

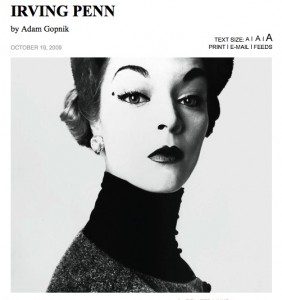

In the postwar years, America was unduly blessed by its art dealers, who offered an open door to the avant-garde, and by its fashion magazines, in which a handful of photographers managed to turn fashion pictures into another kind of high art. Chief among them was Irving Penn, who died last week, at the age of ninety-two. There are many instinctive romantics among popular artists, the Gershwins and the Chaplins who, through force of spirit and originality of style, take by storm the balcony and the boxes alike. Penn was something rarer, an instinctive popular classicist, with a magical gift for visual rhythm, for making something insignificant—a pattern of cigarettes and ashes, each ash miraculously in its one best place—look as formally inevitable as an eighteenthcentury still-life. If Richard Avedon, his great rival and competitor, was a snapshot Delacroix, all fire and figures, Penn was Ingres with a Leica, all ravishing edges and perfect composition and a quality of deep color that was the envy of every other photographer.