One thing to be said for RyanAir (and, God knows, there little enough to be said for that single-minded organisation) is that its fierce baggage restrictions force one to be selective when going on holiday. 10kg is the cabin-baggage limit, and once you’ve packed a Nikon D700 and a couple of lenses, a laptop plus charger, phone plus ditto, well, you’re half-way there. So while sitting by a pool in Provence is a great place to read all those massive tomes (e.g. Michael Sandel’s Democracy’s Discontent: America in Search of a Public Philosophy) that have been sitting reproachfully on one’s desk all year, RyanAir obliges one to leave them behind.

Accordingly I went looking among the piles of books that I’ve been looking forward to reading and came up with this trio:

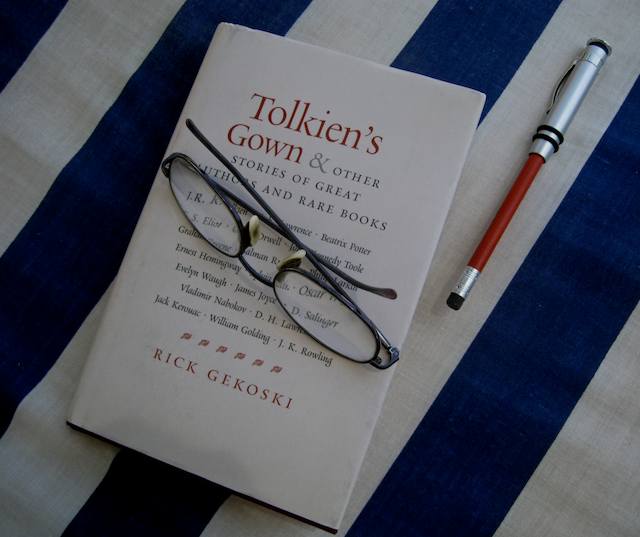

That I have Tolkien’s Gown with me is the outcome of a happy accident. One of my Wolfson Press Fellows last Term was Phil Kitchin, a well-known New Zealand investigative journalist. On his arrival in Cambridge, I came into College to greet him and found that he had been driven up by his sister and her husband; they live in London and he’d been staying with them for a few days. I suggested that we all go somewhere decent for lunch and we repaired to the Three Horseshoes in Madingley, one of my favourite haunts (and one which last year wowed the Guardian’s restaurant critic for its “beautiful, imaginative, authentic rustic Italian cooking, served in huge quantities at fair prices”).

It proved a very enjoyable meal. Phil’s sister and her husband turned out to be terrific company — witty, smart and knowledgeable. I hadn’t caught their surname when we were introduced, but I had picked up that the chap was called Rick. He was large, bearded and amiable. I picked up during the conversation that he was an American, had been an academic (at Warwick), had a D.Phil from Oxford and was a dealer in rare books, in which occupation he had obviously prospered. He also seemed extremely well informed about lots of things — including James Joyce, who happens to be one of my literary heroes. All in all, it made for an agreeable lunch (for which he generously paid), after which I drove them back to College, said goodbye and thought no more of it.

A few days later, I ran into Phil and he handed me a book — Tolkien’s Gown. “Rick asked me to give you this”, explained Phil. “He’s reading your book.” (I must have mentioned at some point that I’d written a history of the Net.) It seemed only fair that I should reciprocate so I opened the book and began to read the Introduction. At which point I had to stop. This, I thought, is too delicious to be read in the work-hassled, utilitarian frame of mind I was then in. (As a multi-tasker who has not been programmed with the right algorithm, I’m always chasing my tail.) So I put Tolkien’s Gown away for a moment when the time would be right.

That moment came when packing for Provence. And now in the peace and quiet of this blessed part of the world, I’ve read it. It’s a collection of short essays tracing the publishing history of twenty significant modern books, each of which is sought after by collectors of first editions. But this means that it’s also a kind of fragmentary autobiography, because Mr Gekoski is a rare book dealer and his story intersects with that of the books. “For”, he writes, “each of us who has the fun and privilege to deal with great books has stories to tell: of where a rare book came from, and how, and where it ended up. And — which people always find compelling — how much money was involved.”

Rick is an American who came to Merton College, Oxford, to do a doctorate in English. It was while he was in Oxford that he discovered that there was money to be made in buying and selling rare books. It started (as many things do) with a 20-volume set of Dickens which he bought for £10 and sold for £20 in order to purchase for his girlfriend “one of those fashionable Afghan coats, covered in embroidery, smelling distinctly yakky”. He does not, alas, relate whether the recipient of this garment became his wife, or exited stage left pursued by donkeys and the mangier kind of dog.

After Oxford he went to Warwick University as a lecturer in the English Department, of which he eventually became head. Like me, he found that an academic salary was not sufficient to pay for the life he wished to lead, so first he supplemented it by playing poker, and later by being a rare book ‘runner’ — i.e. “someone who buys books and sells them on to the trade”. In the end, he decided to give up his tenured but straitened employment and become a professional dealer — quite a bold decision for a man who at the time had a wife and two kids to support. “When I announced my (early) retirement”, he recalls, “one of my colleagues slunk into my office, and confessed that he through it ‘very brave’ of me to be leaving the department. I told him that, when I contemplated another twenty-five years as a university teacher, I thought it brave of him to stay. He wasn’t amused.” But it looks as though Gekoski had the last laugh: in his first year he made twice his university salary “and had a hundred times more fun”. My guess is that he has earned many multiples of a professor’s salary every year since.

The book started out as a series of Radio 4 programmes entitled Rare Books, Rare People, which I’d completely missed when they were broadcast. Like all radio programmes in this genre, they relied a lot on archival recordings (e.g. of Frieda Lawrence recalling how difficult D.H. was; or Evelyn Waugh lambasting Joyce’s writing as “gibberish” — with a hard ‘g’). But that stuff doesn’t play in print, so for the book the original scripts were rewritten and extended — and the number of books covered increased to twenty.

The title comes from the fact that in his first year at Oxford Gekoski lodged in a Merton College house at 21 Merton Street. After he’d left, J.R. Tolkien (who had been the Merton Professor of English) moved into the house and Charley Carr, the man who had been Rick’s ‘Scout’ (i.e. college servant), rang to say that the new occupant wanted him to help clear out a lot of unwanted rubbish. “You liked Mr Tolkien’s books, didn’t you?” he asked. “Very much”, replied Rick, hopefully. “Well”, said Charley, “he’s asked me to throw out his old college gown, and I was thinking maybe old Rick would want it”.

Of course he would have preferred some of old JR’s library, but he took the gown and it went into his second dealer’s catalogue in 1983 with the description “original black cloth, slightly frayed and with a little soiling, spine sound”. It sold for £550 and Charley had a fortnight’s holiday in Cornwall on the back of the sale.

Tolkien’s Gown is full of stories like this, many of them revealing details about, or insights into, books that have changed our lives. For years, for example, I’ve been puzzled about the longevity of William Golding’s Lord of the Flies on GCSE reading lists. It’s been on them forever. I know it’s a great book, but, really… (In fact I know an English teacher who quit partly because he couldn’t stand the idea of teaching it to yet another cohort of bored teenagers who would be programmed to regurgitate the same conventional wisdom.)

Gekoski’s essay on the book is a delightful use of inside knowledge: he’d worked with Golding on a comprehensive bibliography of his work. The task didn’t exactly appeal to the great man, who likened it to drinking his own bathwater. His account of the genesis of Lord of the Flies is fascinating. It starts with Golding returning from the war and reflecting on what he had seen. “By the time I had found out”, Golding wrote, “what men had done to each other, what men had done to their own people, really then I was forced to postulate something which I could not see coming out of normal human nature as portrayed in good books.” Returning to schoolmastering after the war, Gekoski portrays Golding looking afresh at the boys in his care. “His pupils didn’t know it at the time”, he writes, “but his horror at man’s inhumanity to man was slowly transforming itself into a new but related interest: boys’ inhumanity to boy”.

As with lots of the other books, Lord of the Flies took quite a while to find a publisher. And even when it got to its eventual publisher (Faber & Faber), Gekoski recounts how it was nearly kyboshed by the firm’s professional Reader, a Miss Parkinson, who was supposed to have a gift for summing up a book in a single paragraph. Her summing up of Golding’s masterpiece read: “Time: the future. Absurd and uninteresting fantasy about the explosion of an atomic bomb in the colonies and a group of children who land in jungle country near New Guinea. Rubbish and dull. Pointless.”

There’s lots more like that in Tolkien’s Gown. It’s a gem of a book, swamped by the avalanche of print that is published each year. In that sense, it reminds me of Gardner Botsford’s memoir, A Life of Privilege, Mostly which was recommended to me by Sean French, a friend who has a nose for great stuff. Botsford was an editor on the New Yorker for decades and has a lovely, understated, unpompous style. But as far as I can see his book sank without trace. And yet, like Rick Gekoski’s collection, it’s a gem.