The man himself

Jaques-Emile Blanche’s portrait of James Joyce, now in the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Quote of the Day

“All great truths begin as blasphemies.”

- George Bernard Shaw

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

John McCormack | Love’s Old Sweet Song

This was recorded in October 1927 with Edwin Schneider at the piano. McCormack was a contemporary of Joyce and suggested in 1904 that he should enter the national singing competition (the Feis Ceoil) that he (McCormack) had won the previous year. Dermot Bolger, the Irish theatre director, has written an entertaining account of what happened:

McCormack encouraged Joyce to enter the 1904 Feis, hoping that Joyce would emulate his success and enjoy a similar year in Italy, away from his poverty in Dublin.

Joyce’s Feis Ceoil dreams were not shattered by McCormack, but by Joyce’s erratic preparations. He took his singing seriously enough to rent a large room from a family on Shelbourne Road – they unwitting joined Joyce’s long list of patrons as he was tardy at paying rent.

He even conned the famous Piggott’s shop into delivering a grand piano – being careful to be out when it arrived, thereby avoiding tipping the workmen who hauled it upstairs.

However he didn’t make any attempt to learn how to read music – despite knowing that the Feis rules required him to sing an easy but unseen song on sight.

Joyce’s voice so impressed the distinguished judge that he was a shoo-in for the gold medal until he stormed off stage in high dudgeon when he was presented with a sheet of unseen music and asked to sing from it. Snatching defeat from the jaws of victory, he disqualified himself. The stymied judge could only eventually present Joyce with a token bronze medal.

Joyce claimed that he had thrown the medal into the river Liffey in disgust, but in fact he gave it to his aunt Josephine and somehow it wound up later in the possession of Michael Flatley, the celebrated Irish dancer and the artist behind Riverdance.

Joyce was indeed a genius, but much of the time he was what in Dublin would be known as a right royal pain in the ass. There’s a famous story in his brother’s memoirs of him accosting W.B. Yeats, the greatest Irish literary figure of the day, outside the National Library in Kildare Street, and saying to the great man “I regret that you are too old to be influenced by me”.

Long Read of the Day

Misreading Ulysses

The text of novelist Sally Rooney’s T.S Eliot Lecture, delivered at the Abbey Theatre in Dublin on October 23, 2022.

It’s terrific. Here’s a sample:

Joyce’s prose is famous, in this novel and elsewhere, for its density, its radical novelty, and for its exquisite and unexpected beauty. For this reason, I think, Ulysses is a book that is often experienced “partly.” If you ask a person whether they have read, for example, Crime and Punishment, the answer is pretty much always yes or no. But if you ask whether someone has read Ulysses, the answer is often “bits of it, but not the whole thing.” What gives Ulysses this quality—this “bits of it” appeal—is that so many passages of the work can yield a rich and immersive pleasure even outside the context of the overarching narrative. In the history of the English novel, this style represents a definitive break from the established nineteenth-century tradition. Even the word style is misleading, because throughout the novel, as you probably know, Joyce cycles through any number of distinctive styles, using and discarding them as they suit his purposes. In a sense, then, maybe my plot summary was beside the point: maybe the real pleasures and triumphs of Ulysses are on the level of the sentence. To an extent, I think, but not entirely. Joyce’s language is certainly very beautiful, but he wasn’t the first or only talented prose stylist of his generation—and there’s more going on in Ulysses than fine writing.

The brilliant novelist and critic Anne Enright recently wrote: “Apart from everything that you could possibly imagine, nothing much happens in Ulysses.” It’s very true. We might sense something daringly lifelike in the way that Ulysses rejects the contrivances of traditional plots and structures. And maybe it is this quality, this sense of “faithfulness to reality,” that gives the book its special place in literary history. Here are some of Bloom’s thoughts, for instance, as he walks toward Sweny’s pharmacy to get a special lotion made up for his wife:

He walked southward along Westland row. But the recipe is in the other trousers. O, and I forgot that latchkey too. Bore this funeral affair. O well, poor fellow, it’s not his fault. When was it I got it made up last? Wait. I changed a sovereign I remember. First of the month it must have been or the second.

None of this mental fretting on Bloom’s part serves any of the usual purposes of novelistic prose. Nothing in the plot of the book actually depends on whether he gets the lotion made up for Molly or not. On the contrary, he’s just thinking, the way we all think, aimlessly, doubling back, worrying, forgetting, remembering. In our real lives, thoughts don’t occur to us in service of some grander narrative or final meaning: we just wake up, think all day long, and then go to sleep.

A very sharp and perceptive lecture.

Books, etc.

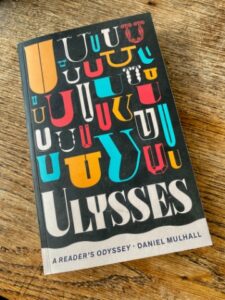

Dan Mulhall, the former Irish Ambassador to the US (and before that, to the UK) is the only high-profile diplomat I know who tweets about literature — especially about Joyce, Yeats and Seamus Heaney. He’s currently the Parnell Fellow at Magdalene College — you can find his big lecture here. I’ve read and enjoyed this perceptive and unpretentious guide to Ulysses. And look forward to his forthcoming book on W.B. Yeats.

My commonplace booklet

Remembering Robert Gottlieb, Editor Extraordinaire

David Remnick, Editor of the New Yorker has written a lovely piece about one of his predecessors, who has just passed away. It’s graceful and memorable, like everything Remnick writes.

This is how it opens:

Early this year, Film Forum, the redoubtable revival house on West Houston Street, drew overflow crowds for a documentary about two elderly men squaring off over semicolons and commas. The film, “Turn Every Page,” starred the semicolon-deploying biographer Robert Caro and the semicolon-averse editor Robert Gottlieb, who for many years was the head honcho at Simon & Schuster and then at Alfred A. Knopf, and from 1987 to 1992 was the editor of The New Yorker. Their relationship—intense, wary, mysterious—lasted a half century. It began with “The Power Broker,” Caro’s biography of Robert Moses, which, to its author’s agony, Gottlieb trimmed by some three hundred and fifty thousand words.

Audiences at Film Forum thrilled to the climactic scene in which Caro and Gottlieb sit side by side in an antiseptic office, intently reviewing a manuscript page from Caro’s study of Lyndon Johnson. These two secular Talmudists are hunched over the page, sharing a pencil and arguing about matters of punctuation, syntax, rhythm, and clarity. There is a deep bond between them, a distinctly unsentimental partnership in which everything is about purpose, choices, and decisions, never sloppy praise or even encouragement.

In a Paris Review interview, Caro said, “In all the hours of working on ‘The Power Broker,’ Bob never said one nice thing to me—never a single complimentary word, either about the book as a whole or about a single portion of the book. That was also true of my second book, ‘The Path to Power,’ the first volume of the Johnson biography. But then he got soft. When we finished the last page of the last book we worked on, ‘Means of Ascent,’ he held up the manuscript for a moment and said, slowly, as if he didn’t want to say it, ‘Not bad.’ ”

You see what I mean? The annoying thing is that I haven’t yet been able to get to see the damned film.

In the meantime, the trailer is here!

This Blog is also available as a daily email. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email a day, Monday through Friday, delivered to your inbox. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!