Whitegate

As regular readers will know, I am trying to re-learn the art of black-and-white photography, after years and years of working in colour. B&W requires one to ‘see’ things differently — to look for structure, contrast, subtle changes in light and shadow.

This gate would look banal in colour, and yet it struck me as interesting when I passed it yesterday.

Quote of the Day

”If God wanted us to fly, He would have given us tickets.”

- Mel Brooks

(Came to mind while reading some fatuous nonsense about flying cars.)

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Namadingo Ft. Giddes Chalamanda | Linny Hoo

Enchanting song by an extraordinary musician.

Thanks to Anne Chapel for suggesting it.

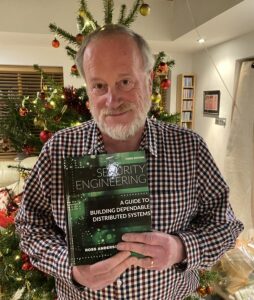

Remembering Ross

Ross Anderson died unexpectedly in his sleep last Thursday, leaving a large group of us devastated. He was one of those unforgettable people — fabulously erudite, generous with his knowledge and friendship, fiercely independent, and fearless. He had a kind of flinty integrity that was wholly admirable, which meant that he was often a thorn in the side of university, governmental and academic establishments, who discovered that he was no pushover.

He was a Fellow of the Royal Society and a recipient of the British Computer Society’s Ada Lovelace Medal. He was a world authority on computer security, cybercrime and cryptography. He was Professor of Security Engineering at Cambridge, and leaves behind a remarkable cohort of PhD students who were lucky enough to have him as a supervisor.

Many people found him formidable and indeed sometimes forbidding. He didn’t do small talk. And yet when you were lucky enough to get to know him (as I was) he was great company. He and I used to walk round the ‘800’ Wood near Cambridge with his two lovely dogs, deep in conversation about the sordid ingenuity of cyber-criminals, the short-sightedness of academic administrators, the intrusiveness of national security agencies, as well as about Celtic folk music of which he knew a lot. (He was a piper and shared my interest in Uileann piping.)

I learned such a lot from those conversations. Ross changed the way I looked at computing, and alerted me to the political economy of the technology which has shaped my thinking ever since. He always spoke his mind — which is why when an email from him would arrive at 8am on Sunday mornings I knew that he had read my Observer column and had something to say about it, and accordingly braced myself before reading further.

The last time I saw him was a few weeks ago, when we both snuck into a talk given by Matt Clifford (who has become Rishi Sunak’s go-to man on “AI Safety”). He had been invited by a student group, and Ross and I were the only two grizzled veterans in the room. Before Clifford embarked on his boosterish talk, I got out my pen to take notes, and then noticed that Ross had opened his MacBook. So I put my pen away. He always took the most detailed and accurate notes of any event he attended, and I knew that if I needed to check something later about Clifford’s performance, Ross’s record would provide the evidence I needed.

Ross was furious about Cambridge University’s remorseless determination to force academics to retire at 67, and he had been mounting a campaign against the policy. At 5pm on the day he died, he had an email conversation with one of his colleagues, Jon Crowcroft, about the possibility of harnessing generative AI to add spice to the campaign. Ross sent Jon a link to a song he had just prompted suno.ai to create.

As Jon observed afterwards, it could almost serve as an obituary.

Ross’s death marks the passing of the last of the five computer scientists who made Cambridge such a pioneering centre of research in the field — Maurice Wilkes, Roger Needham, David Wheeler, Karen Spärck Jones and Ross.

May he rest in peace. We were lucky to have known him.

Frank Stajano, one of Ross’s colleagues in the Computer Lab, has written a lovely tribute to him in the blog that Ross and his colleagues have been running since 2006.

Long Read of the Day

What Have Fourteen Years of Conservative Rule Done to Britain?

You know the answer, but this sharp New Yorker essay by Sam Knight gives some useful detail.

Sample:

Some people insisted that the past decade and a half of British politics resists satisfying explanation. The only way to think about it is as a psychodrama enacted, for the most part, by a small group of middle-aged men who went to élite private schools, studied at the University of Oxford, and have been climbing and chucking one another off the ladder of British public life—the cursus honorum, as Johnson once called it—ever since. The Conservative Party, whose history goes back some three hundred and fifty years, aids this theory by not having anything as vulgar as an ideology. “They’re not on a mission to do X, Y, or Z,” as a former senior adviser explained. “You win and you govern because we are better at it, right?”

Another way to think about these years is to consider them in psychological, or theoretical, terms. In “Heroic Failure,” the Irish journalist Fintan O’Toole explains Brexit by describing Britain’s fall from imperial nation to “occupied colony” of the E.U., and the rise of a powerful English nationalism as a result. Last year, Abby Innes, a scholar at the London School of Economics, published “Late Soviet Britain: Why Materialist Utopias Fail,” which argues that, since Thatcher, Britain’s political mainstream has become as devoted to particular ideas about running the state—a default commitment to competition, markets, and forms of privatization—as Brezhnev’s U.S.S.R. ever was. “The resulting regime,” Innes writes, “has proved anything but stable.”

Read on. It’s perceptive, realistic … and depressing (if you live in the UK).

How did a developer of graphics cards for gamers become the third most valuable firm on the planet?

Yesterday’s Observer column:

A funny thing happened on our way to the future. It took place recently in a huge sports arena in San Jose, California, and was described by some wag as “AI Woodstock”. But whereas that original music festival had attendees who were mainly stoned on conventional narcotics, the 11,000 or so in San Jose were high on the Kool-Aid so lavishly provided by the tech industry.

They were gathered to hear a keynote address at a technology conference given by Jensen Huang, the founder of computer chip-maker Nvidia, who is now the Taylor Swift of Silicon Valley. Dressed in his customary leather jacket and white-soled trainers, he delivered a bravura 50-minute performance that recalled Steve Jobs in his heyday, though with slightly less slick delivery. The audience, likewise, recalled the fanboys who used to queue for hours to be allowed into Jobs’s reality distortion field, except that the Huang fans were not as attentive to the cues he gave them to applaud.

Still, it made for interesting viewing. Huang is an engaging speaker and he has built a remarkable company in the years since 1993, when he first sketched his idea for Nvidia in a Silicon Valley diner. And the audience were in awe of him because they regard him as a man who saw the future long before they did, and hoped to catch a glimpse of what might be coming next.

And in this they were not disappointed…

Do read the whole thing

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 6am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!