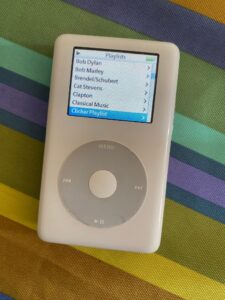

This is my old iPod Classic.

It was a present from a wealthy and generous friend many years ago, when 40GB iPods were seriously expensive (he brought six of them to a dinner at our house one winter’s evening and distributed them like Santa Claus). It was my favourite device — the container of all my recorded music. And then, after quite a long time, it died, and ever since has sat on the windowsill in my study next to other treasured icons (like my piece of the Berlin Wall).

Recently, though, I decided that we should restore it to life, and I enlisted the help of my 12-year-old grandson Jasper in the project. Given that he’s been running his own 3D printer for a couple of years, I guessed that it would be, er, child’s play. And, in a way, it was.

From the outset, our guess was that the iPod’s demise could be due to one — or perhaps two — problems: a dead battery plus (possibly) a failed hard disk. We bet on the battery, and ordered a replacement from iFixit.

I also ordered one of their terrific toolkits (which, among other things, contain every screwdriver head that the fiends at Apple have ever devised to discourage device owners from messing with Jony Ive’s jewellery boxes).

Initially, I thought that the biggest hurdle might be opening the device, but some YouTube research revealed that it would yield to determined pressure, and it did.

Since we were all meeting up in Provence I brought the dissassembled device, plus the new battery and the toolkit and Jasper settled down to extract the (clearly knackered) old battery and insert its replacement.

He then reassembled the device, clicked the plastic cover into place, and — miming nonchalance — we hooked it up to power and to a speaker.

From the fact that I’m writing this to the sound of Van Morrison singing Days Like This you can guess the outcome. There are indeed days like this, when everything works as it should.

Two morals of the story.

- Owners should have the Right to Repair their devices.

- And every blogger should have a grandson who knows what he’s doing.

Footnote. Two other thoughts were striking. The first is how physically large a 40GB disk was once upon a time. The second is how different Apple’s production system was when my iPod was made — compared to the glossy, slick perfectionism of the iPhone era. Here’ for example, is what the old battery looked like.