Who you lookin’ at, mister

Brancaster Staithe, Norfolk.

Quote of the Day

”I hate to advocate drugs, alcohol, violence, or insanity to anyone, but they’ve always worked for me.”

- Hunter S. Thompson

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

Bob Dylan | Ring Them Bells

Long Read of the Day

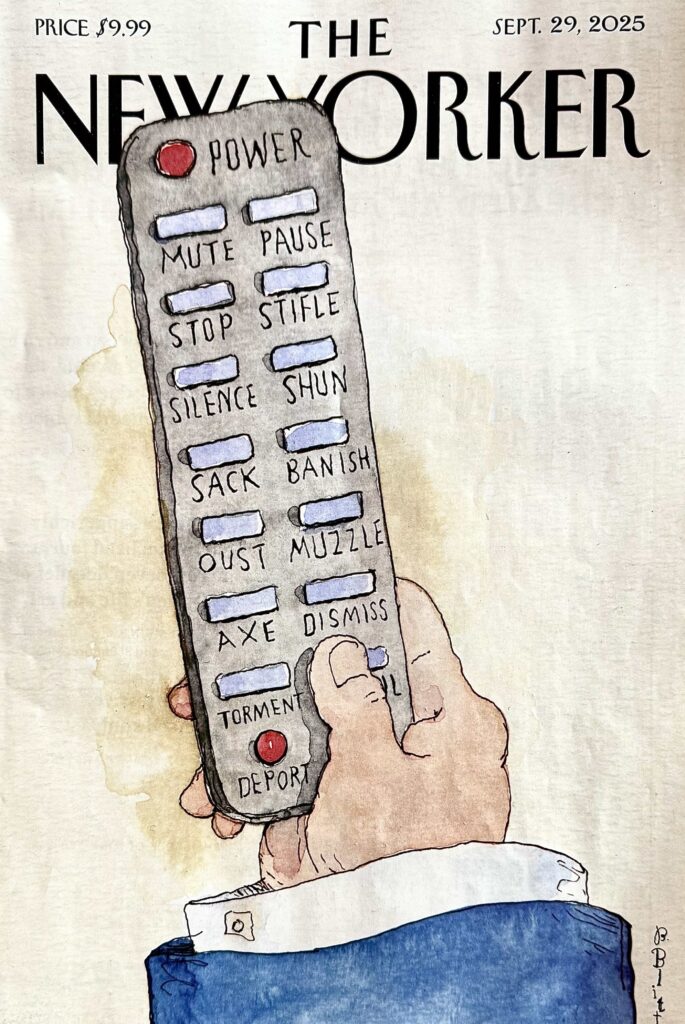

Personal reflections on a Trumpian 2025

Christina Pagelis a mathematician and a physicist and Professor of Operational Research at UCL. She is also the most diligent monitor we have of the Trump regime’s relentless assaults on American democracy. In this piece she looks back on a pretty grim year.

I started to track Trump’s actions to help me make sense of it, and then to help others make sense of it. I’m continuing because it’s become a contemporaneous record of what is happening – a bearing witness to the loss of American freedom, tolerance and democracy. It’s also there as a warning for us and the populist anti-democratic movements in our countries, that are also increasingly adopting the language and symbols of white supremacy.

As someone with German parents, who lived through the 2nd World War and grew up in a Germany grappling with the enormity of its crimes, I had believed that the imagery of the Nazi years was gone for good. Seeing it return via the US Department of Homeland Security social media feed has been horrifying. …

Do read it. Her TrumpActionTracker now stands at over 2100 recorded actions and informs thousands of visitors every week.

My commonplace booklet

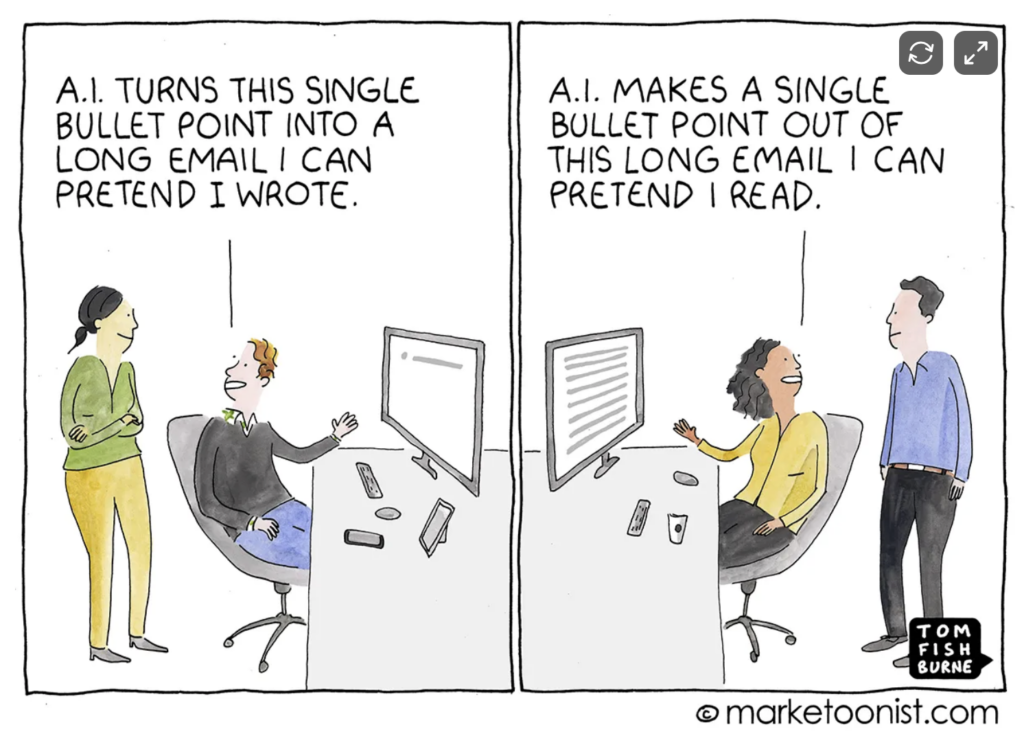

The Fishburne Effect

Great cartoonist. You can follow him – and order some of his collected work — at The Marketoonist website.

Linkblog

Something I noticed, while drinking from the Internet firehose.

- Jesse Welles | Join ICE

Neat satirical recruitment song. Video here.

Here’s the first verse:

Well, if you’re lookin’ for purpose in the current circus

If you’re seekin’ respect and attention

If you’re in need of a gig that’ll make you feel big

Come with me and put some folks in detention

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 5am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!