… this has to be a spoof. Doesn’t it?

Category Archives: Beyond belief

Believe it or Not!

The United Kingdom is one of America’s closest allies. The nations have together fought multiple wars, and remain closely tied commercially, politically, and militarily. Yet a 2006 National Geographic survey of young [American] adults found that only one in three could find the United Kingdom on a map.

From The Atlantic.

The same source claims that a 1999 Gallup poll revealed that 20 percent of Americans think that the sun revolves around the earth.

Beware what you “Like”…

… it may come back to haunt you.

This from the New York Times.

SAN FRANCISCO — On Valentine’s Day, Nick Bergus came across a link to an odd product on Amazon.com: a 55-gallon barrel of … personal lubricant.

He found it irresistibly funny and, as one does in this age of instant sharing, he posted the link on Facebook, adding a comment: “For Valentine’s Day. And every day. For the rest of your life.”

Within days, friends of Mr. Bergus started seeing his post among the ads on Facebook pages, with his name and smiling mug shot. Facebook — or rather, one of its algorithms — had seen his post as an endorsement and transformed it into an advertisement, paid for by Amazon.

In Facebook parlance, it was a sponsored story, a potentially lucrative tool that turns a Facebook user’s affinity for something into an ad delivered to his friends.

Amazon is one of many companies that pay Facebook to generate these automated ads when a user clicks to “like” their brands or references them in some other way. Facebook users agree to participate in the ads halfway through the site’s 4,000-word terms of service, which they consent to when they sign up.

You have been warned.

The Greek ‘election’

Interesting piece by Slavoj Žižek in the LRB.

The next round of Greek elections will be held on 17 June. The European establishment warns us that these elections are crucial: not only the fate of Greece, but maybe the fate of the whole of Europe is in the balance. One outcome – the right one, they argue – would allow the painful but necessary process of recovery through austerity to continue. The alternative – if the ‘extreme leftist’ Syriza party wins – would be a vote for chaos, the end of the (European) world as we know it.

The prophets of doom are right, but not in the way they intend. Critics of our current democratic arrangements complain that elections don’t offer a true choice: what we get instead is the choice between a centre-right and a centre-left party whose programmes are almost indistinguishable. On 17 June, there will be a real choice: the establishment (New Democracy and Pasok) on one side, Syriza on the other. And, as is usually the case when a real choice is on offer, the establishment is in a panic: chaos, poverty and violence will follow, they say, if the wrong choice is made. The mere possibility of a Syriza victory is said to have sent ripples of fear through global markets. Ideological prosopopoeia has its day: markets talk as if they were persons, expressing their ‘worry’ at what will happen if the elections fail to produce a government with a mandate to persist with the EU-IMF programme of fiscal austerity and structural reform. The citizens of Greece have no time to worry about these prospects: they have enough to worry about in their everyday lives, which are becoming miserable to a degree unseen in Europe for decades.

Such predictions are self-fulfilling, causing panic and thus bringing about the very eventualities they warn against. If Syriza wins, the European establishment will hope that we learn the hard way what happens when an attempt is made to interrupt the vicious cycle of mutual complicity between Brussels’s technocracy and anti-immigrant populism. This is why Alexis Tsipras, Syriza’s leader, made clear in a recent interview that his first priority, should Syriza win, will be to counteract panic: ‘People will conquer fear. They will not succumb; they will not be blackmailed.’ Syriza have an almost impossible task. Theirs is not the voice of extreme left ‘madness’, but of reason speaking out against the madness of market ideology. In their readiness to take over, they have banished the left’s fear of taking power; they have the courage to clear up the mess created by others. They will need to exercise a formidable combination of principle and pragmatism, of democratic commitment and a readiness to act quickly and decisively where needed. If they are to have even a minimal chance of success, they will need an all-European display of solidarity: not only decent treatment on the part of every other European country, but also more creative ideas, like the promotion of solidarity tourism this summer.

[…]

Here is the paradox that sustains the ‘free vote’ in democratic societies: one is free to choose on condition that one makes the right choice. This is why, when the wrong choice is made (as it was when Ireland rejected the EU constitution), the choice is treated as a mistake, and the establishment immediately demands that the ‘democratic’ process be repeated in order that the mistake may be corrected. When George Papandreou, then Greek prime minister, proposed a referendum on the eurozone bailout deal at the end of last year, the referendum itself was rejected as a false choice.

Well, up to a point, Lord Copper. I agree with that last para, because what’s been clear for decades is that the European ‘Project’ is, at its heart, a profoundly undemocratic one in the sense that a large proportion of the citizens of European democracies don’t feel represented within the Euro machine and probably have never voted for it. An academic colleague of mine who has spent many months in EU committees discussing science and technology policy once told me that there was one infallible way of getting Eurocrats riled, and that was to ask whether a particular venture would be a defensible use of “taxpayers’ money”. My friend intuited that it was the idea that taxpayers might be in any way relevant to these questions that really irritated the Eurocrats.

Likewise, the fact that my fellow-countrymen in Ireland rejected the Lisbon Treaty in a referendum was famously regarded by Brussels as the ‘wrong’ result. The Irish was told to go back to the ballot box and vote differently (and they did). This is a bit like Brecht’s famous dictum that if the people reject the government then it is time to dissolve the people and get a better crowd.

On the other hand, it’s really difficult to work up too much sympathy for a society in which tax-evasion and a bloated public sector are as pervasive as they have been in Greece. Consider, for example, Micheal Lewis’s celebrated report on the country which contained passages such as this (about the Greek public sector):

As it turned out, what the Greeks wanted to do, once the lights went out and they were alone in the dark with a pile of borrowed money, was turn their government into a piñata stuffed with fantastic sums and give as many citizens as possible a whack at it. In just the past decade the wage bill of the Greek public sector has doubled, in real terms—and that number doesn’t take into account the bribes collected by public officials. The average government job pays almost three times the average private-sector job. The national railroad has annual revenues of 100 million euros against an annual wage bill of 400 million, plus 300 million euros in other expenses. The average state railroad employee earns 65,000 euros a year. Twenty years ago a successful businessman turned minister of finance named Stefanos Manos pointed out that it would be cheaper to put all Greece’s rail passengers into taxicabs: it’s still true. “We have a railroad company which is bankrupt beyond comprehension,” Manos put it to me. “And yet there isn’t a single private company in Greece with that kind of average pay.” The Greek public-school system is the site of breathtaking inefficiency: one of the lowest-ranked systems in Europe, it nonetheless employs four times as many teachers per pupil as the highest-ranked, Finland’s. Greeks who send their children to public schools simply assume that they will need to hire private tutors to make sure they actually learn something. There are three government-owned defense companies: together they have billions of euros in debts, and mounting losses. The retirement age for Greek jobs classified as “arduous” is as early as 55 for men and 50 for women. As this is also the moment when the state begins to shovel out generous pensions, more than 600 Greek professions somehow managed to get themselves classified as arduous: hairdressers, radio announcers, waiters, musicians, and on and on and on. The Greek public health-care system spends far more on supplies than the European average—and it is not uncommon, several Greeks tell me, to see nurses and doctors leaving the job with their arms filled with paper towels and diapers and whatever else they can plunder from the supply closets.

Or this, about tax evasion:

A handful of the tax collectors, however, were outraged by the systematic corruption of their business; it further emerged that two of them were willing to meet with me. The problem was that, for reasons neither wished to discuss, they couldn’t stand the sight of each other. This, I’d be told many times by other Greeks, was very Greek.

The evening after I met with the minister of finance, I had coffee with one tax collector at one hotel, then walked down the street and had a beer with another tax collector at another hotel. Both had already suffered demotions, after their attempts to blow the whistle on colleagues who had accepted big bribes to sign off on fraudulent tax returns. Both had been removed from high-status fieldwork to low-status work in the back office, where they could no longer witness tax crimes. Each was a tiny bit uncomfortable; neither wanted anyone to know he had talked to me, as they feared losing their jobs in the tax agency. And so let’s call them Tax Collector No. 1 and Tax Collector No. 2.

Tax Collector No. 1—early 60s, business suit, tightly wound but not obviously nervous—arrived with a notebook filled with ideas for fixing the Greek tax-collection agency. He just took it for granted that I knew that the only Greeks who paid their taxes were the ones who could not avoid doing so—the salaried employees of corporations, who had their taxes withheld from their paychecks. The vast economy of self-employed workers—everyone from doctors to the guys who ran the kiosks that sold the International Herald Tribune—cheated (one big reason why Greece has the highest percentage of self-employed workers of any European country). “It’s become a cultural trait,” he said. “The Greek people never learned to pay their taxes. And they never did because no one is punished. No one has ever been punished. It’s a cavalier offense—like a gentleman not opening a door for a lady.”

The scale of Greek tax cheating was at least as incredible as its scope: an estimated two-thirds of Greek doctors reported incomes under 12,000 euros a year—which meant, because incomes below that amount weren’t taxable, that even plastic surgeons making millions a year paid no tax at all. The problem wasn’t the law—there was a law on the books that made it a jailable offense to cheat the government out of more than 150,000 euros—but its enforcement. “If the law was enforced,” the tax collector said, “every doctor in Greece would be in jail.” I laughed, and he gave me a stare. “I am completely serious.” One reason no one is ever prosecuted—apart from the fact that prosecution would seem arbitrary, as everyone is doing it—is that the Greek courts take up to 15 years to resolve tax cases. “The one who does not want to pay, and who gets caught, just goes to court,” he says. Somewhere between 30 and 40 percent of the activity in the Greek economy that might be subject to the income tax goes officially unrecorded, he says, compared with an average of about 18 percent in the rest of Europe.

Žižek is right that our enslavement to a particular manifestation of neo-liberal capitalism threatens to undermine democracy. The problem for his case is that the Greeks are not a great argument for it. A better example might be Ireland, a country in which every man, woman and child is now in debt to the tune of €17,000 because of their government’s insane decision to indemnify banks for their crazed borrowing and lending. In the last General Election, my countrymen threw out the crooks (Fianna Fail) who had got the country into this mess, but elected a crew who — at least in one respect — were just “Fianna Fail Lite”, and who have insisted in sticking to the ludicrous commitment entered into by their predecessors. The result: an austerity programme on steroids, and a predictable recession.

Of course — as with the Greeks — my countrymen are not exactly blameless either. Apart from tolerating the pervasive corruption of their politicians and of the planning system, they also enthusiastically mounted the ‘Celtic Tiger’ and goaded it energetically into a gallop in the belief that the laws of economics had been suspended, that property bubbles go on forever, and so on. So I’m left with the thought that while we get the governments (or at least the politicians) that we deserve, we also got a banking system and an economic ideology

that none of us voted for and even fewer of us understood.

Gadaffi’s ghost returns to haunt Sarko

From Philippe Marlière’s wonderful rolling diary of the 2012 French presidential election.

After Marshall Pétain’s cameo earlier this week, Muammar Gaddafi’s ghost has invited himself to the campaign. Mediapart, a respected news website, has revealed today that Gaddafi’s regime had agreed to fund Nicolas Sarkozy’s 2007 campaign to the tune of 50 million euros. Mediapart produced a 2006 document in Arabic which was signed by Gaddafi’s foreign intelligence chief. The letter referred to an “agreement in principle” to support Sarkozy’s campaign. All major media have mentioned the story. Will they hold the president to account? I wouldn’t hold my breath. Most French journalists are tame and deferential to powerful politicians. The most servile of them, smelling blood, have started to be a bit more combative of late. But this is too little and too late.

Markets are always spooked. Period.

Well, well. It seems that the collapse of the Dutch government and the prospect of a new French president has “spooked” the markets. Well, of course it has: markets are fundamentally irrational organisms — as Keynes pointed out many decades ago. One moment the bond market is spooked by the thought that governments might not be able to implement the ‘austerity’ programs that will push their countries into downward economic spirals. The next moment, the market is spooked by the thought that the prospect of economic growth is rendered less likely by austerity measures. So trying to run a country in such a way that the bond markets are satisfied is not only absurd, but impossible. Yet that is the essence of the Cameron/Osborne economic strategy.

The academic publishing racket: curiouser and curiouser

My Observer column about the academic publishing racket has caused a bit of a stir, which is gratifying. Cory Doctorow gave it a great boost by picking it up in Boing Boing. And then, in typical Cory fashion, he added this intriguing sting in the tail, raising a question that had never occurred to me.

Here’s an interesting wrinkle I’ve encountered in a few places. Many scholars sign work-made-for-hire deals with the universities that employ them. That means that the copyright for the work they produce on the job is vested with their employers — the universities — and not the scholars themselves. Yet these scholars routinely enter into publishing contracts with the big journals in which they assign the copyright — which isn’t theirs to bargain with — to the journals. This means that in a large plurality of cases, the big journals are in violation of the universities’ copyright. Technically, the universities could sue the journals for titanic fortunes. Thanks to the “strict liability” standard in copyright, the fact that the journals believed that they had secured the copyright from the correct party is not an effective defense, though technically the journals could try to recoup from the scholars, who by and large don’t have a net worth approaching one percent of the liability the publishers face.

Of course, to pursue this line, you’d have to confront the fact that academics are sharecroppers to their employers, and that the works they’ve published, posted to their websites, licensed for anthologies, etc, aren’t theirs, which would have a lot of fallout beyond mere academic publishing circles. But it’s still provocative to consider the possibility that the journals (and their enormous, conglomerated parent companies) might owe something like 40 years’ worth of the entire planet’s GDP to a bunch of cash-strapped universities.

Gosh! It’d be interesting to see what academic employment contracts say about this nowadays.

The BoingBoing post attracted a lot of good comments, including this from Steve Runge:

The fact that academics don’t know what the library pays for journal subscriptions is well-known by librarians. In fact, that’s the basis for shifting the burden of payment to the author/funder, to avoid precisely that moral hazard. Believe me, librarians are working their kiesters off to make OA easier for the laziest of the lazy. It just takes a while to get everyone rowing at the same time and in the same direction. The trouble spots: 1. every journal has a different policy regarding copyright. If we’re going to help lazybones professors put their pre-prints in publicly available electronic repositories, we’ll need either a) unambiguous language inserted forcibly into all publishing contracts giving universities first rights or b) a whonking big updated database of publishers’ contract language regarding repositories. 2. Prof’s don’t know, for the most part, how close this system is to collapse, and just how thoroughly publishers have libraries over a barrel. 3. Tenure and promotion review policies that are based almost exclusively on impact factor are basically a sop to Elsevier and other big publishers. If T & P review policies were also to include download counts of repository articles or other measures of dissemination & influence, tenure-track publishing behavior would broaden into open access.

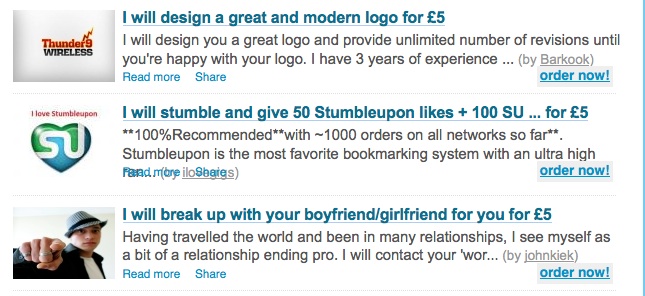

Cheap thrills, er, services

I know that the Net is a great disintermediator, but this is something else.

The academic publishing racket

This morning’s Observer column.

But it’s not just the exorbitant subscriptions that stink; it’s the intrinsic absurdity of what’s involved in the academic publishing racket. Most publishers, after all, have at least to pay for the content they publish. But not Elsevier, Springer et al. Their content is provided free by researchers, most of whose salaries are paid by you and me.The peer reviewing that ensures quality in these publications is likewise provided gratis by you and me, because the researchers who do it are paid from public money. One estimate puts the value of UK unpaid peer reviewing at a staggering £165m. And then the publishers not only assert copyright claims on the content they have acquired for nothing, but charge publicly funded universities monopoly prices to get access to it.The most astonishing thing about this is not so much that it goes on, but that people have put up with it for so long. Talk to university librarians about extortionist journal subscriptions and mostly all you will get is a pained shrug. The librarians know it’s a racket, but they feel powerless to act because if they refused to pay the monopoly rents then their academics – who, after all, are under the cosh of publish-or-perish mandates – would react furiously and vituperatively.Which is why the recent initiative by a Cambridge academic, Tim Gowers, is so interesting and important. Professor Gowers is a recipient of the Fields medal, which is the mathematics equivalent of a Nobel prize, so they don’t come more eminent than him…

One of the most encouraging things to happen int he last couple of weeks is to find that even the Economist, that bible of unfettered ‘free’ enterprise, has concluded that the racket has to be stopped.

George Monbiot published a characteristically robust critique of the racket last year in which he said that outfits like Elsevier “make Murdoch look like a socialist.”

If you’re an academic, you can sign up to the Cost of Knowledge pledge here. When I last checked, nearly 10,000 academics had signed up.

The first sign that Tim Gowers’s broadside was having a serious impact was the release by Elsevier of a typical PR-driven damage-limitation response: it’s headed “A MESSAGE TO THE RESEARCH COMMUNITY: JOURNAL PRICES, DISCOUNTS AND ACCESS”. Tim Gowers’s elegant dissection of it is here.

Some of my librarian colleagues have commented that the tipping point will come only when researchers in the medical and life sciences rebel. The physicists and mathematicians have long ago got the point — which is why arXiv.org is so successful and important in their world of scholarly publication. The good news is that the Wellcome Trust, which funds an awful lot of life-science research, now has an enlightened open-access publishing policy. What it needs to do next is to enforce it on its grantees. Only that way will the political naivete and solipsism of many researchers be overcome. Money talks, even in the most abstruse circles. All that is needed is a few well-publicised test cases in which recipients of Wellcome grants who don’t comply with the requirement are banned from further funding. Nothing concentrates the academic mind like the prospect of a funding refusal.

LATER: Jon Crowcroft writes:

“I’d like to point out that the leading academic publsher for Computer Science conference proceedings and many journals, the ACM, has for a long time allowed authors to put open access PDFs on their own institutional or personal web pages for free, plus now lets you publish a link that is free and openly reachable by anyone (not just paid up ACM digital library subscribers) to their archival version. For me, this is pretty exemplary. What is more, some of their conferences (which I am at now in califonia) publish 100% free and open access PDFs for papers _before_ the conference….given the prestige of the ACM, I see no excuse for computer science academic authors _ever_ to submit to paywalled ripoff commercial for profit journals or venues. Citation impact will doom them in any case, so there’s a game theory reason these bad people will lose in the end:)”

Hypocrisy squared

More from the incredible but true department.

1. King Juan Carlos, monarch of Europe’s biggest basket-case economy (which has 50% youth unemployment), has been constantly bleating about how he lies awake at night worrying about the plight of his subjects. And then we discover that he’s been on a $10,000 a day safari in Africa shooting elephants, if you please.

2. Cameron & Co announce their determination to go after all those plutocrats who use ingenious wheezes to avoid paying tax in the UK. And guess what? It turns out that Cameron’s inheritance came via an ingenious wheeze cooked up by his Dad and involving tax havens.