I’m an engineer. I don’t understand finance, but I know something about how systems work, about feedback and complexity and emergence. And when I watch or read media ‘explanations’ of the banking crisis I invariably find that some aspects of the story seem to be missing.

All open dynamic systems, for example, have inputs which they transform into outputs — like so:

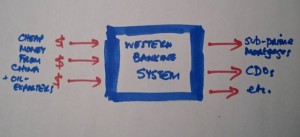

We know that the global financial system went into overdrive creating products that turned out to be unbelievably toxic. So an obvious question — to an engineer at least — is: where did the money come from to make these dodgy loans possible? What were the inputs to this crazy system? The answer turns out to be incredibly cheap money from China and the oil-rich Middle Eastern countries:

So: cheap money in, dodgy financial products out. As the Greenspan-sponsored post 9/11 economic boom gathered pace, China found itself running an enormous balance-of-trade surplus. So, to a lesser extent, did those countries which produce crude oil. They all found themselves with huge revenues and nowhere to put them to productive use. So they lent wholesale — at very low interest rates, because after all the supply of funds outstripped demand, thereby driving down interest rates — to Western banks and financial institutions. These, in turn, finding themselves able to obtain vast quantities of money cheaply, looked for ways of turning a profit on it. They could — and presumably did — lend some of it to credit-worthy institutions. But that was a finite market. So they looked around for a marketing opportunity — and found it in all those hard-up folks who aspired to buy a house but had hitherto been unable to obtain a mortgage. As one banker said on Dispatches the other night, it got to the point where “if you could breathe” someone would offer you a mortgage.

Now you might argue that these simple input-output models are too crude to be taken seriously. And perhaps they are. But I’ve just come on an interesting paper by an American economist, James Hamilton, which he presented at a conference organised by the Brookings Institution, a very fancy Washington-based think tank. Professor Hamilton is a student of oil prices and their impact, and he had previously published some stuff about the long-term impact of the oil-price rises in 2003. On his blog he wondered what the recent spike in oil prices might mean.

One of the most interesting calculations for me was to look at the implications of my 2003 model. I used those historically estimated parameters to find the answer to the following conditional forecasting equation. Suppose you knew in 2007:Q3 what GDP had been doing up through that date and could know in advance what was about to happen to the price of oil. What path would you have then predicted the economy to follow for 2007:Q4 through 2008:Q4?

The answer is given in the diagram below. The green dotted line is the forecast if we ignored the information about oil prices, while the red dashed line is the forecast conditional on the huge run-up in oil prices that subsequently occurred. The black line is the actual observed path for real GDP. Somewhat astonishingly, that model would have predicted the course of GDP over 2008 pretty accurately and would attribute a substantial fraction of the significant drop in 2008:Q4 real GDP to the oil price increases.

He goes on:

“The implication that almost all of the downturn of 2008 could be attributed to the oil shock is a stronger conclusion than emerged from any of the other models surveyed in my Brookings paper, and is a conclusion that I don’t fully believe myself. Unquestionably there were other very important shocks hitting the economy in 2007-08, first among which would be the problems in the housing sector. But housing had already been subtracting 0.94% from the average annual GDP growth rate over 2006:Q4-2007:Q3, when the economy did not appear to be in a recession. And housing subtracted only 0.89% over 2007:Q4-2008:Q3, when we now say that the economy was in recession. Something in addition to housing began to drag the economy down over the later period, and all the calculations in the paper support the conclusion that oil prices were an important factor in turning that slowdown into a recession.

This is intriguing, but it’s also another black-box, input-output model. In Professor Hamilton’s case it’s oil-shocks in, economic downturn out.

Deep waters, eh, Holmes? But wouldn’t it be funny if we could predict large-system behaviour with such crude models.